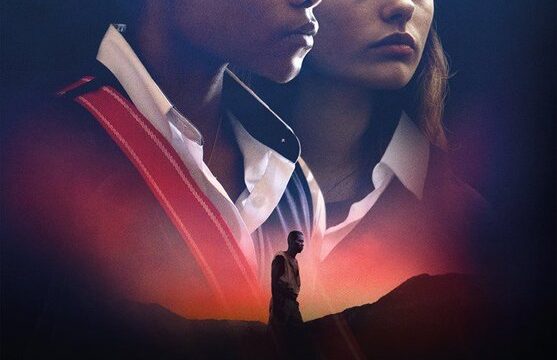

At the intersection of a fairy tale and a cautionary tale lies Bertrand Bonello’s Zombi Child. The newest film from the director of the 2017 feature Nocturama, Zombi Child concerns Melissa (Wislanda Louimat), who has just moved to a new school in France from her old life in Haiti. Melissa feels isolated in this environment, though she eventually finds a friend in Fanny (Louise Labeque). Her new pal is part of a very exclusive clique that eventually allows Melissa to become its newest member. Even with four new friends, Melissa still feels lonely, mostly because Fanny and her cohorts tend to (both intentionally and unintentionally) treat Melissa as an “other” in their lives.

Meanwhile, intersecting across Melissa’s story is the saga of Clairvius Narcisse (Mackenson Bijou), a man in Haiti who was pronounced dead but then brought back to life as a zombie to work in local sugar cane fields. Even in death, the bonds of slavery still find a way to ensnare black people. Additionally, there is also the character of Mambo Katy (Katiana Milfort), Melissa’s mother. A master of voodoo, she eventually becomes a figure of particular interest of Fanny. You see, Fanny’s boyfriend has left her and she’s very upset about it. So upset, in fact, that she wants to, with the help of Mambo Katy, bond his soul to hers through the practice of voodoo.

Zombi Child is working with a number of plotlines but Bonello’s screenplay actually juggles them all quite well. It helps that they’re all united by a singular theme regarding the dehumanization of Black people from Haiti and their cultures. Whether it’s in the more heightened segments focused on Clairvius or Melissa’s more grounded school life, this element is constantly around. In the case of Melissa, this detail manifests in how aspects of Melissa’s culture are deemed “weird” or “creepy” by Fanny and her friends. Meanwhile, Fanny only sees the world of voodoo as something she can use to her own end. She wants to take something near and dear to a non-white culture and exploit it for her own gain.

Though Fanny sees Mambo Katy as just a means to an end, Zombi Child certainly doesn’t. Prior to Fanny entering her life, Bonello smartly delivers a number of scenes showcasing Katy in her everyday life. She checks up on her daughter, she relaxes, she tutors a young boy. White people tend to have a caricatured idea about voodoo and those who practice it. In the insightful hands of Zombi Child, characters connected to voodoo-like Mambo Katy and Clairvius are allowed to become fully-rendered people. This lends the exploration of multigenerational racial trauma real weight. After all, the human beings affected by that trauma have been painted as vivid characters defined by more than just their pain. Exploring a multi-faceted character Melissa is interesting. Exploring a pain-ridden stereotype is not.

Meanwhile, Bornello lends similar creativity to the visuals of Zombi Child. Each different storyline has a much different visual aesthetic to it. The inherently stylized nature of the Clairvius subplot, for example, is reinforced through heavy uses of blue color grading, moody shadows, and more pronounced camera angles. By contrast, scenes set in Melissa’s school have a much more rigid visual style. Bright whites and equally vibrant lights are the default visual choices anytime we stop by this area. To boot, the intimate scenes with Mambo Katy have a more naturalistic look to them, complete with a more varied color palette across the walls and furniture in her house.

Bornello’s thoughtfulness on a thematic and visual level makes Zombi Child an exceptionally interesting experience, particularly when the final ten minutes arrive. This is when the storylines converge. The past, the present and the future, they all collide here in a sequence depicting Mambo Katy performing a voodoo ritual on Fanny while Melissa informs Fanny’s friends about the saga of Clairvius. It’s all truly unnerving to watch and much of that can be owed to the editing by Anita Roth. It’s impressive how her well-timed cuts between Fanny and Melissa don’t manage to undercut the tension of either scene. Zombi Child could have easily buckled under its own weight here but Roth’s editing gracefully cuts between both storylines to ensure the ominous tension is maintained.

This final sequence is also a great showcase for the acting chops of Wislanda Louimat. In this scene, Louimat’s Melissa finally gets the chance to talk about her own culture and past to people who have long been diminishing both entities. This means each word that Louimat speaks here has a sense of great personal importance. Louimat quietly but effectively conveys just how deeply important this story is to Melissa. Throughout the entirety of Zombi Child, Louimat is quite impressive at that sort of acting. Subdued yet distinctive, a great reflection of the kind of attitude Melissa has to adopt to get any kind of social acceptance in her new school environment. Her richly human lead performance provides a great anchor for the ambitious and fascinating zombie tale Zombi Child.