In its second season, The Man in the High Castle (now streaming on Amazon and free for Prime subscribers) finally starts paying off on its premise. That premise and little else about the series came straight from Philip K. Dick’s early novel: we are in an alternate-universe 1962 America, one in which Germany and Japan won WW2 and now both occupy the country in an uneasy truce, Germany to the east and Japan to the West, with the Rockies as a Neutral Zone. A set of newsreels emerge and get smuggled by a Resistance to the Man in the High Castle, newsreels from our universe. The first season almost completely ignored the way this upset our basic grounding in reality and authenticity, settling instead for three not-that-interesting characters (Alexa Davalos as Juliana, Luke “Armie Hammer’s Annoying Younger Brother” Kleintank’s Joe, and Rupert Evans’ Frank) chasing after the MacGuffin of one of the films.

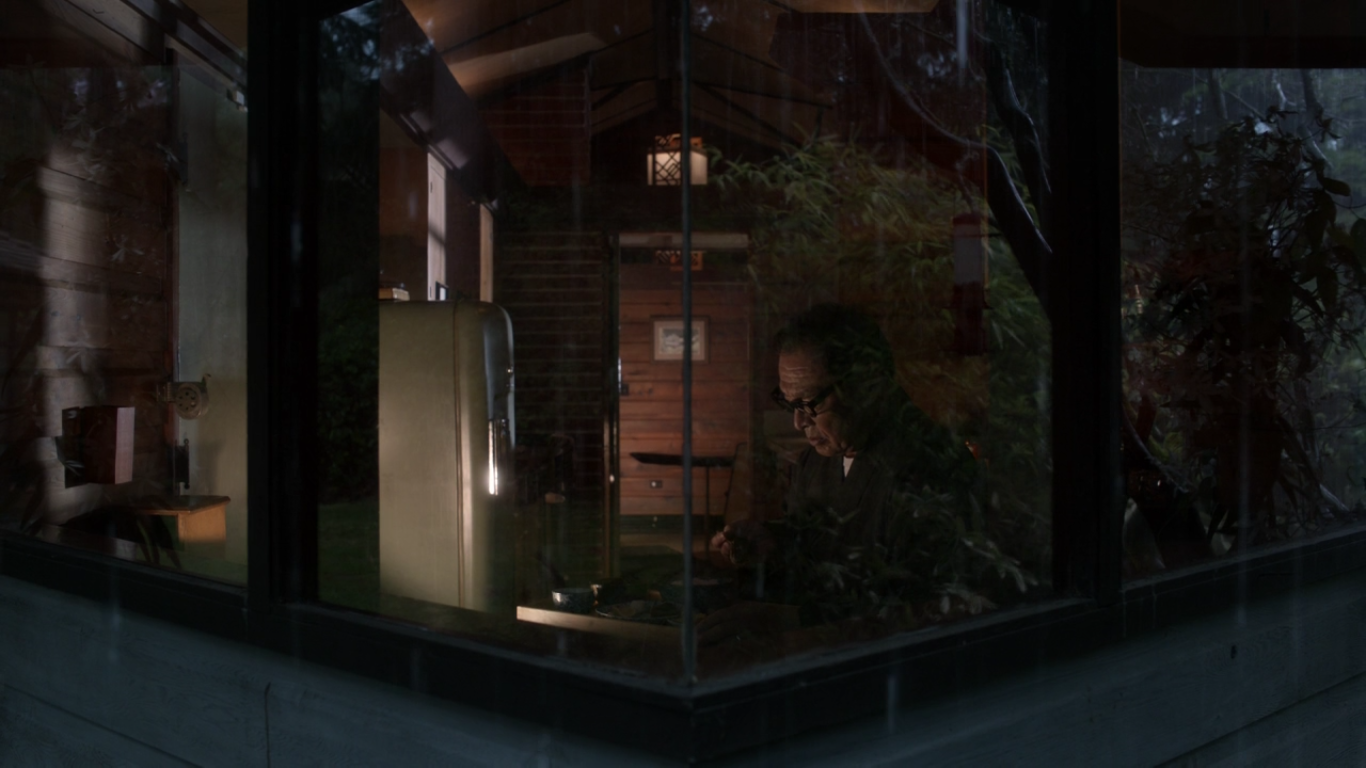

In this season’s first episode, though, Shit Gets if not Real (one does not use that word casually with Dick) then definitely Interesting. It was suggested visually in last season’s finale that the Man was Hitler, but thankfully that idea gets abandoned and we shall never speak of it again. The Man appears less than thirty minutes into this season, played by National Goddamn Treasure Stephen Root. (By now I’ve seen him play what feels like twenty eccentric characters, never twice the same way.) His High Castle is a warehouse (with two windows up high and a huge door below, the resemblance to the interior of a skull is unmistakable; he says “this is my castle, right here, the conscious and unconscious mind”) filled with film reels, all from different universes, all things that didn’t happen but might happen. Reality here isn’t a single thing but a range of possibles, and that range gives him clues as to what to do in this one. He throws down a challenge to identity that will play out over these ten episodes:

You learn an awful lot watching these films. Some of us are the same: rotten or kind in one reality, rotten or kind in the next, but most people are different, depending on whether they have food in their belly or hungry, safe or scared.

It’s an idea that Lost played with in its final season but not successfully: whether or not people have a consistent identity across realities. The Man in the High Castle now does what Dick did best: take philosophical questions and tell stories about them, where the ideas aren’t played out at the level of theme but as choices the characters have to confront. This scene also kicks the plot into gear: all the films end with the atomic destruction of San Francisco, except one that has someone Juliana almost recognizes (Tate Donovan) and now has to find.

SPOILERS to follow, but I’ll try to keep them to a minimum until the end.

The character who faces that choice most clearly is Trade Minister Tagomi (Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa). In the final moment of season one, he briefly switched into the 1962 of our reality; this season, after a few blips, he completely jumps into it. (His moment of transition is an elegant bit of cinematic staging, like the reveal of Walter White in the finale of Breaking Bad or Bernie Birnbaum in Miller’s Crossing.) In our reality, it’s the Cuban Missile Crisis, he’s about to get divorced, and he has a son, a grandchild, and a daugher-in-law–Juliana. Tagomi faces a choice: would it be better to live as a good man in a bad world, or a bad man in a good one? As in the first season, Tagawa plays his character quietly and simply, and with a sense of weight to all his actions, making us feel his displacement, his fear, and his responsibility. Without ever saying so openly, the writers use these scenes to answer some questions: where have the newsreels been coming from? Has anyone else gone between worlds? Are you or they different in different worlds? (Exactly how Tagomi made the jump is never explained, nor should it be. Dick’s strain of science fiction always took the realities as a given, and showed people trying to cope with that.) It’s the most effective and touching aspect of the show so far.

Tagomi gets the best story of the season, but once again the best performance and most interesting character is Rufus Sewell’s Obergruppenführer John Smith. The strangeness of his performance really matters here. Sewell has a voice like gravel in motor oil, and there’s this humor to it that never goes away; just him saying “Joe” always comes across as a private joke. He never makes the choice that a normal person or actor would, whether it’s anger or grief or happiness; he’s the kind of guy who responds to getting called out in a lie not just with honesty but with entitlement and pride, a sense of “of course I lied to you, because you can be lied to.” Both larger than life and a hardass professional, he’s like Daniel Day-Lewis’ Bill the Butcher in uniform, a man born to hierarchy. Yet his strangeness keeps coming through: Tagomi displaces himself to another world; as an American-born Nazi, Smith is always in this world and he’s always displaced. (We get a brief, crucial flashback to a moment when he was an American soldier.) Sewell plays the smartest motherfucker in the room so well (dude was Alexander Hamilton in John Adams) and Smith convincingly pulls off two brilliant schemes over the course of the season, the second of which makes him quite possibly the most powerful man in the German Reich. His penultimate moment, as he realizes this, is an exemplar of David Mamet’s rule for great acting: invent nothing, deny nothing. Smith didn’t expect this to happen, but he can truly accept it, and the way he plays this moment plus the earlier flashback create the slightest possibility that he’s actually been covertly working against the Nazis all along. If a third season happens and goes this way, Sewell could bring it off. Another strong aspect of this season is that’s not all there is to Smith. He’s placed in real danger this season and Sewell plays some real fear, something new to the character. One is that Hitler tasks him with tracking down the Man in the High Castle (“you’re worried.” “He’s worried”), the other is a development from last season: his son Thomas (Quinn Lord) has been diagnosed with muscular dystrophy and, as a “defective,” has to be turned over to the authorities to be killed. This subplot quickly reveals that Smith’s highest loyalty is his family; it reveals the same thing in his wife Helen, and Chelah Hordsal plays just as much strength as Sewell does. Both of them are the perfect American Nazis right up to the moment their children are threatened. The story of also illustrates one of the contradictions at the heart of Nazi ideology: it idealized the nuclear family, and like all totalitarianisms, demanded that Nazism itself be a higher ideal than that.

Another strong aspect of this season is that’s not all there is to Smith. He’s placed in real danger this season and Sewell plays some real fear, something new to the character. One is that Hitler tasks him with tracking down the Man in the High Castle (“you’re worried.” “He’s worried”), the other is a development from last season: his son Thomas (Quinn Lord) has been diagnosed with muscular dystrophy and, as a “defective,” has to be turned over to the authorities to be killed. This subplot quickly reveals that Smith’s highest loyalty is his family; it reveals the same thing in his wife Helen, and Chelah Hordsal plays just as much strength as Sewell does. Both of them are the perfect American Nazis right up to the moment their children are threatened. The story of also illustrates one of the contradictions at the heart of Nazi ideology: it idealized the nuclear family, and like all totalitarianisms, demanded that Nazism itself be a higher ideal than that.

The portrayal of life under Nazi rule is subtly but decisively different in this season. There are fewer overt signifiers of it. Most of them come from Juliana’s plot, as she goes to the East Coast and gets caught between Smith’s family and the Resistance. There’s a disturbing scene where Juliana gets subjected to a full physical examination to classify her racially, and another where she’s studying for the Reich’s citizenship test. (That leads to the funniest moment of the series, a slam on American exceptionalism and self-righteousness: “Now we’ll learn about American exterminations before the Reich.” “Exterminations?” “. . .Didn’t they ever teach you about the Indians?”) Mostly, though, the series engages more with the psychology of Nazism than the look (same holds true on the Japanese-dominated West Coast) and there’s nothing like the “Three Monkeys” episode of last season, where we saw what Veteran’s Day looks like in the American Reich. Also notable by its absence: unlike last season, there’s almost no mention of Jews or Judaism. Last season had someone talking about the smell of the death camps in the pilot, and Michael Gaston leading his family through Jewish ritual in secret. Frank is Jewish, but only a single dream sequence shows that, and he refers to it only once. What comes across here is a vision of Nazism without hatred, not less lethal or less evil, where “defectives” or “useless eaters” get quietly disposed of. It’s a vision based on perfection and discarding everything else, the technocratic vision of Nazis like the architect Albert Speer (and we see some of the Berlin he wanted to build in this season). Here, that vision gets embodied in Joe’s father (Sebastian Roché), a high-ranking Reichsminister, planning to build a dam between the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, and a big chunk of this season is about his rise to power. With him, you see the utopian vision of the Nazis, the other side of their medieval cult of blood and hate. What’s scary about this is how much sense it makes as alternative history: if the Nazis became like this, that means they really had killed everyone else. If this season sometimes feels like it accepts Nazism, that’s because it’s a vision of a world when there was no longer any alternative.

What comes across here is a vision of Nazism without hatred, not less lethal or less evil, where “defectives” or “useless eaters” get quietly disposed of. It’s a vision based on perfection and discarding everything else, the technocratic vision of Nazis like the architect Albert Speer (and we see some of the Berlin he wanted to build in this season). Here, that vision gets embodied in Joe’s father (Sebastian Roché), a high-ranking Reichsminister, planning to build a dam between the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, and a big chunk of this season is about his rise to power. With him, you see the utopian vision of the Nazis, the other side of their medieval cult of blood and hate. What’s scary about this is how much sense it makes as alternative history: if the Nazis became like this, that means they really had killed everyone else. If this season sometimes feels like it accepts Nazism, that’s because it’s a vision of a world when there was no longer any alternative.

Already a lot of people have drawn parallels to this world and ours right now; sure, but the feeling of being alienated in your own homeland has been true for a lot of people in a lot of places and times, and it’ll happen again. Maybe the truest expression of that comes from Thomas, who comes to realize his sickness and that he’ll be marked as a defective. A Hitler Youth, he seems ready to die, but not to become the thing despised by everyone–including himself. When Juliana reassures him that he’s not worthless, he cries “Then why does everybody think that way? Why is it the law?” But they could get inside you, Orwell wrote in 1984, and that may be the worst part about oppression: the way it takes people and turns their friends, their families, finally their own psyches against themselves. With no one left to hate, the oppressors turn on themselves, turn on their children–and that’s also a detail the Resistance, on both sides of the country, knows and uses. That kind of moral complexity is one of the best things about this season. Another is the direction: despite a rotating crew of directors, these episodes are have a unified look and a gorgeous one. The color palette tends towards dark reds and browns; it’s the kind of autumnal look The Sopranos went for so many times. When Tagomi makes the jump into our world, the colors start to broaden but not excessively so and it goes into a slightly soft focus; it looks different without announcing itself. The spaces are cramped until we get to Berlin, a place of huge offices–great touch that Hitler’s office is set up so that we can never see him when the doors open–and open forests, and the giant Volkshalle is the biggest space of all. There’s a lot of centered compositions, often with Tagomi, which fits a classical Japanese world of order. One major weakness can’t be blamed on the directors: the first four episodes don’t go much of anywhere. I kept wondering “is the destruction of San Francisco no longer a thing? We’re not worried about that anymore?” (There’s also some occasionally iffy CGI.) The show kicks into gear in the fifth episode (where Tagomi makes the jump), and then into a higher gear with the strong seventh episode (featuring good, subtle direction by Karyn Kusama and a plot turn) and stays there almost to the end.

That kind of moral complexity is one of the best things about this season. Another is the direction: despite a rotating crew of directors, these episodes are have a unified look and a gorgeous one. The color palette tends towards dark reds and browns; it’s the kind of autumnal look The Sopranos went for so many times. When Tagomi makes the jump into our world, the colors start to broaden but not excessively so and it goes into a slightly soft focus; it looks different without announcing itself. The spaces are cramped until we get to Berlin, a place of huge offices–great touch that Hitler’s office is set up so that we can never see him when the doors open–and open forests, and the giant Volkshalle is the biggest space of all. There’s a lot of centered compositions, often with Tagomi, which fits a classical Japanese world of order. One major weakness can’t be blamed on the directors: the first four episodes don’t go much of anywhere. I kept wondering “is the destruction of San Francisco no longer a thing? We’re not worried about that anymore?” (There’s also some occasionally iffy CGI.) The show kicks into gear in the fifth episode (where Tagomi makes the jump), and then into a higher gear with the strong seventh episode (featuring good, subtle direction by Karyn Kusama and a plot turn) and stays there almost to the end.

As with the first season, there’s a deep bench of supporting actors. In addition to Stephen Root, Rick Worthy and the incomparable Callum Keith Rennie show up in the first episode as Resistance members (from my notes: “oh good, the adults are here”) and stick around to the end. We also see veteran TV and film actors like Roché, Hordsal, Emily Holmes as a friend of the Smiths, Cara Mitsuko as a Japanese resistance fighter (she gets a great conversation with Frank about racism), Valerie Mahaffey and Tate Donovan as East Coast members of the Resistance, DJ Qualls as Frank’s best friend Ed, Tzi Ma as a Japanese warrior general, Joel de la Fuente as Inspector Kido (when he teams up with Smith, it makes perfect sense–they’re both the professionals here), and Brennan Brown as Robert Childan. A dealer in fake antiques, Childan comes from the novel and stays closest to it in spirit. He’s written pretty much only as comic relief, but like Alison Tolman in Mad Dogs, the performance transcends that. Brown just brings too much self-awareness and intelligence to his performance; he’s funny, but he also has a real dignity to him, and he and Qualls have such great chemistry I wanted to go back to the lower pressure of the novel and just hang out with the two of them. The Second Golden Age of Television has given so many opportunities for actors who have been stuck in the background: they bring their distinctive looks and experience to their shows, and The Man in the High Castle really takes advantage of them this time. Sadly, I can’t include the three leading actors on this list, although it’s not really the fault of two of them. Alexa Davalos does her best as Juliana, and it’s nice to see her get a variation on her character in our world. She and Rupert Evans as Frank have the same problem of having their characters written as impossibly naïve. Juliana just seems shocked that the Resistance is mad at her and doesn’t trust her, after she ended last season by, y’know, handing off a film that Resistance members died for to a fucking Nazi agent. (Also, I’m pretty sure running into an embassy and yelling out the identity of one of their spies is not the best way to seek asylum.) Frank keeps showing his disapproval that the Resistance takes action that provokes Japanese reprisals (a good way to get me to instantly dislike a character: have them ask questions to which everyone, including me, knows the answer). He also perpetually insults and pushes around Ed, who ended last season by essentially sacrificing himself and his family to save Frank. Juliana and Frank have been written as the classical American innocents (usually white), the kind who take a journey to learn about and fight the badness of the world but who are just so darn good and innocent at their core. That’s bad enough in any setting–it turns privilege into virtue. Here, given that they’ve spent over half their lives under foreign occupation, they come off as unforgivably stupid more than anything else.

Sadly, I can’t include the three leading actors on this list, although it’s not really the fault of two of them. Alexa Davalos does her best as Juliana, and it’s nice to see her get a variation on her character in our world. She and Rupert Evans as Frank have the same problem of having their characters written as impossibly naïve. Juliana just seems shocked that the Resistance is mad at her and doesn’t trust her, after she ended last season by, y’know, handing off a film that Resistance members died for to a fucking Nazi agent. (Also, I’m pretty sure running into an embassy and yelling out the identity of one of their spies is not the best way to seek asylum.) Frank keeps showing his disapproval that the Resistance takes action that provokes Japanese reprisals (a good way to get me to instantly dislike a character: have them ask questions to which everyone, including me, knows the answer). He also perpetually insults and pushes around Ed, who ended last season by essentially sacrificing himself and his family to save Frank. Juliana and Frank have been written as the classical American innocents (usually white), the kind who take a journey to learn about and fight the badness of the world but who are just so darn good and innocent at their core. That’s bad enough in any setting–it turns privilege into virtue. Here, given that they’ve spent over half their lives under foreign occupation, they come off as unforgivably stupid more than anything else.

Once again, Luke “I Can Play This Scene Indifferent or Petulant; What’s Good for You?” Kleintank sets new depths of bad acting for the series. He still can’t be bothered to do any kind of expression or commitment, and putting him next to actors like Sewell and Roché just makes it more obvious–for the most part, he can’t even be bothered to stand up straight. Davalos and Evans do their best with bad writing, but the script enhances Kleintank’s weaknesses. The worst thing you can do with a bad actor is give him nothing to do, because then they either indicate emotions or sit around being boring, and for about four episodes while Juliana and Frank risk their lives, pull off daring escapes, drill into bombs, or infiltrate the heart of the American Reich, Joe goes to a few parties and finds out his parents lied to him. That’s it, and Kleintank seems convinced that changing his hairstyle between scenes counts as expression. Later in the series, he starts wearing a Nazi uniform and just looks ridiculous; there’s a scene between Joe and Smith where Sewell looks like he’s trying not to burst out laughing. Maybe a gig on Hawaii Five-O would suit him better.

Even all this Kleintanking can’t match the almost breathtaking stupidity of the ending, which takes the worst aspect of Juliana’s character and roughly quadruples down on it. I’m gonna have to go into full SPOILERS now:

Tate Donovan’s character, Dixon, gets a recording of Thomas confessing his sickness to Juliana and will use it to bring down John Smith. Juliana kills Dixon and then Smith stops Germany from launching a nuclear attack on Japan and Japanese territories, including San Francisco; the prophecy of the one film where the city wasn’t destroyed is fulfilled. She gets taken to the Neutral Zone and in a touching moment, we see her burn the recording while Thomas gives himself up to the Nazi authorities to be killed–she didn’t save him at all. Then the Man in the High Castle shows up and gives her a big speech that bookends his one at the beginning: the one thing he saw in all the films was her, her constant innocence–“that woman would do anything to save a sick boy, a Nazi boy even, because she believed he deserved a chance, slim as it might be, to live a valuable life”–and that’s what saved San Francisco. As a big finish, the Man produces Juliana’s sister, shot dead in the pilot, now alive. The one truly good person finds out how good she is, and gets rewarded to the sound of uplifting organs and strings. (All through the series, the score has been intrusive but here it gets absolutely overbearing, copying Hans Zimmer’s climactic music for Interstellar. If you found that ending too bitter, cynical, and low-key, you’ll love this one.)

On the level of plot, this makes zero sense. Juliana’s action of letting Thomas confide in her gave Dixon the chance to bring Smith down, so she could have gotten the same results by staying home–why didn’t the film show that? (We know how stupid an action that was, as the show makes it explicit that her home is bugged and that she knows it.) Worse, this takes whatever moral complexity both seasons had and stuffs it headfirst in a woodchipper. Juliana’s actions are those of a character; she might not be a particularly good character but her choices make sense for her. To have the Man in the High Castle give that speech is to have something pretty close to the God of its world single her and no one else out for praise. Guess all those people in the Resistance don’t really count for much, but hey, they’re engaging in morally complex acts and they’re aware of that complexity, not pure like Juliana; when she said to Dixon “you are no better than the Nazis,” he immediately came back with “Good! Because if we’re going to beat them, we need to be worse,” which is when she shot him in the back. This ending is the worst kind of American optimism, the kind where stupidity gets called “innocence” and gets rewarded, the kind that says “pay no attention to the world as it is, just follow your heart” and then–somehow–not only does everything turn out for the best, but you are just the most special and bestest person ever because you followed your heart. It’s ugly anywhere, but to have this be a major story point of something calling itself The Man in the High Castle feels like a sick joke, like retroactively rewriting the story into Michael Bay’s It’s a Wonderful Life. Of course, that’s the kind of sick joke that Philip K. Dick would write, too.