Kingdom Come is famous for ushering the Dark Age out of comic books. For those locked out of the loop, the Dark Age of comic books is generally agreed to be from about 1985 to 1996, beginning with the release of both Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns. Both comics had an explosive influence on the superhero genre; while there were dark and political comics before these two works, they essentially gave comics creators and audiences permission to create and enjoy greater levels of violence, sexual content, and political discussion, as well as grittier and edgier art styles. From my position as a casual comics fan a) too young to have been there live and b) mostly more interested in the culture around superhero comics than the comics themselves, the Dark Age has the absolute worst reputation of all the eras of comic book fashions. It’s mostly remembered for nihilistic violence, deep misogyny, and book after book of ugly, ugly art. People talk about it like it’s the Knocked Out Loaded of comic book eras; it’s described with embarrassment and rage in a way, say, the Silver Age never is. One of the recurring themes in the criticism is that it’s got teenage tryhard rebellion all over it – it’s a boy indulging in sex and violence and looking at his parents with glee, demanding they be shocked so he can laugh in their face.

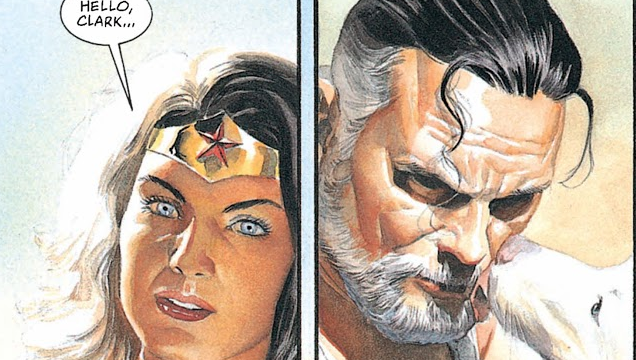

Kingdom Come was hailed as a return to form for the, uh, form – it was a call to throw the smug violent young people in the trash so we can get back to seeing heroes doing heroic things. While I can see what the appeal might have been to comics fans in 1996, thoroughly exhausted by a genre that no longer longer appealed to them, it really doesn’t hold up for me today, either as argument or story. If the Dark Age heroes were teenage boys rebelling without a cause, KC is an old man yelling at a cloud. It’s a story that suffers from a fatal level of certainty; it isn’t just that KC wants things to be one way, it’s that it refuses to even contemplate the arguments of its opponents and so fails to articulate its own counterarguments. Superman is a perfect protagonist of this story, wandering around and sulking whenever anyone criticises him or his views. The fact that the opponents and villains are undercooked is what bothers me most of all; its two arguments are “why doesn’t someone just shoot the Joker?” and “Superman is boring”. The former creates the somewhat convincing argument that violence begets more violence, as more and more heroes resolve situations violently and with greater levels of violence. I can argue with that, but it opens up a conversation. The latter is embarrassingly insecure and I consider it beneath the contempt of any great artist.

One can compare this with the two comics that spawned the trends its reacting to. Any reasonable Watchmen fan knows that it’s not a rejection of superheroes. It shows them from every possible angle; embarrassment and contempt, yes, but also joy and sadness and fear and love. It uses classic cliches of the genre, and even if they go in the wrong direction, there’s still a joy in using them at all. Watchmen sees superheroes from all these different angles and sees them all as simultaneously true; the embarrassment is just as honest as the joy, and the arguments for each angle are complex enough to argue with. The Dark Knight Returns is closer to the mission statement of KC with a focus more on Batman than Superman, showing how our hero adjusts to his modern, cynical times and in turn how he adjust his cynical, modern times to himself. The difference is that even when Frank Miller does not actually get the people he’s writing (like the majority of the women), he does give space to what he believes their views to be. They are characters operating in the world alongside Batman; he might find their views stupid but he’ll articulate them clearly. Mostly this comes down to Miller knowing that great ownage requires great enemies; that Batman winning an argument against a smart person makes him look far cooler than beating up idiots (even if he does that too).

You can also compare it to All-Star Superman. The interesting thing about, uh, ASS is that the criticisms it responds to are all subtextual – clear inspiration for stories that Grant Morrison tells even if they never have a character articulate it. Most notable is the issue of Clark Kent interviewing Lex Luthor, showing in loving detail (with much helpful collaboration from artist Frank Quitely) exactly why nobody would mistake dowdy, milquetoast Clark Kent for the strong and confident Superman. Morrison also shows Superman making choices, all the time. The most common explanation for why Superman is boring is because he can simply punch any problem in his way, and Morrison, understanding that stories are all about decisions, show that Superman’s powers mean that he has to make decisions about his time. Two of the most powerful moments from the comic show this; both a younger Clark realising his father is having a heart attack and rushing to save him, which shows him realising that he is not truly omnipotent and has to pick and choose when to spend his time, and the famous image of him saving a teenage girl from committing suicide. The fact that he’s the most powerful being on Earth and he chose to take a minute out of his day to stop one person from killing themselves is a striking one.

Kingdom Come does have a few striking images. The one I’ve always been touched by is Magog, KC’s invented Dark Age antihero, being struck by remorse over the deaths of civilians in Kansas and giving himself up to Superman to be imprisoned. It’s emotionally engaging with Dark Age heroes in a way that’s honest, if not fully empathetic – self-based empathy that says “if I were in this situation and had done this, this is how I would feel” as opposed to response-based empathy – but the sincerity is moving. It’s a terrible thing to feel the emotions of a man haunted by responsibility for the deaths of many innocents. I’m also moved by Superman’s horror at how Billy Batson has been twisted by Lex Luthor. I think a big part of the reason that people look poorly on the Dark Age is because it was defined by attempts to reshape older heroes to fit a current fad. Batman might be able to work in a variety of tones (part of the appeal of Batman: The Animated Series is because it works in all of them), but Superman calls for a much more limited and specific tone, and ‘edgy nihilistic violence’ ain’t it. The story of Billy Batson being swayed by the dark side and redeeming himself with a nuclear self-sacrifice is a compelling one. The problem is that the rest of the narrative isn’t that good or focused. It’s interesting as a particularly beautiful historical document showing what comics fans felt in 1996 but not much more.