Steven Soderbergh’s The Underneath, if it’s remembered at all, will likely be remembered entirely as the film that not even Soderbergh likes, one which he claims he completely checked out on while he made it (I don’t buy that, but I’ll save that for later). But if Underneath is little-known as a film, it’s perhaps even less known as a remake, a remake of a well-regarded film noir classic, no less. That noir classic is Robert Siodmak’s Criss Cross, which reunited Siodmak with Burt Lancaster, the man he directed in another noir classic, The Killers. They both come from the same source novel (Criss Cross by Don Tracy), and while I haven’t read that, I have seen both films, and together, they make for a fascinating comparison, with the same scenarios taken to radically different places.

The Characters

Criss Cross and The Underneath‘s differences are probably least dramatic in this area. The main character in both is a guy returning to see his mother and brother after a prolonged absence. In Criss Cross, his name is Steve, and in The Underneath, his name is Michael (in the source material, his name is Johnny). In both, he left behind his ex-wife (Anna in Criss Cross, Rachel in The Underneath), who still frequents the bar where they used to hang out. His ex-wife is now involved with a hoodlum named Dundee (Slim in Criss Cross, Tommy in The Underneath) who treats her bad. In both films, Steve/Michael gets a job as an armored car driver, and his father (stepfather in Underneath) is one of his fellow drivers. Back home, Steve’s brother is almost entirely a nonentity in Criss Cross, while Steve’s former best friend, now a detective, is the one who knows of Steve’s less-than-legal operations as the film goes on (more on those later). In The Underneath, Michael’s brother takes that role in place of a best friend, as he’s a cop who knows that Michael was up to no good in the past and is up to no good now. In both films, the mother doesn’t really play much of a role (aside from her being the reason Michael comes back in Underneath), although there are more layers to her personality in Underneath than in Criss Cross, like her desire to win the lottery. In both films, two people at Steve/Michael’s work get into bizarre pseudo-arguments, about one’s wife ordering things on the telephone in Criss Cross and about one’s wife frequently going to the library in The Underneath. There are a few characters in Criss Cross who don’t really have comparable characters in Underneath, like the bartender who gives Steve advice, or the female bar patron who Steve keeps running into. And Underneath also invents characters, namely Joe Don Baker as the head of the armored car company and Elisabeth Shue as a woman Michael meets on the bus to Texas who he keeps running into.

The Plot

In both films, when Dundee catches Steve/Michael with his wife (while they weren’t married when Steve/Michael first saw her, they eloped under his nose and at a time when Steve/Michael thought he would go away with her), Steve/Michael has a way to distract Dundee. He suggests that Dundee carry out a heist of an armored car, with him as the driver and the inside man (there’s an extra inside man in Underneath). Naturally, things go awry. But the things that happen before the shit hits the fan really emphasize the differences between these two films. Siodmak only lets slip that bad feelings between Steve and Ann drove them apart, and they just weren’t right for each other. This all is addressed in one, maybe two discussions by Steve and Anna in the Siodmak film, but Soderbergh is much more interested in what led to their deterioration in his film. Michael is a chronic gambler who may keep Rachel happy when he’s winning, but otherwise, they’re toxic to each other. In flashbacks strewn throughout the film, we see this past Michael being indifferent to his wife and her dreams of being an actress (or even just reading the lottery numbers on TV), making mistakes, and generally just being kind of an asshole. If Soderbergh seems more attached to the flashbacks than he is to the heist itself, the reason is that Soderbergh was going through a nasty divorce at the time, and these scenes are him trying to understand how his life went wrong through Michael’s. Siodmak would have no time for that kind of nonsense in the middle of a tight crime movie, but that nonsense is necessary to Soderbergh, and just as therapeutic to him as the literal nonsense in Soderbergh’s next film, Schizopolis.

The Structure

As mentioned above, Soderbergh adds in many flashbacks to Michael and Rachel’s marriage during the course of the film. These bits take the place of Criss Cross‘s many scenes where the specifics of the heist are explained, which Soderbergh couldn’t care less about. But he takes an even further leap from the linear storytelling of his previous films with the flash-forwards strewn throughout, which show Michael driving in the prelude to the heist. Not that Criss Cross is entirely linear itself. Sure, much of the film is told in strict chronological order, but it opens with Steve and Anna embracing each other on the night before the heist goes down and Steve getting into a planned fight with Dundee to give off the sense to Steve’s friend that the two couldn’t possibly be partners in crime if they hate each other this much. Then we get a scene of Steve driving, waiting for the inevitable, which then fades into the rest of the film, which starts from when Steve goes home to the heist and beyond, with no interruptions. Steve occasionally narrates from the vantage point of him driving, making the film something of a memory piece. Underneath is a memory piece too, but much more of a fractured one (like an actual memory would be), along the lines of Soderbergh’s later The Limey (the seeds of that film’s style are planted with a series of cuts between Michael in the armored cut and Michael being driven home in a taxi and back).

The Style

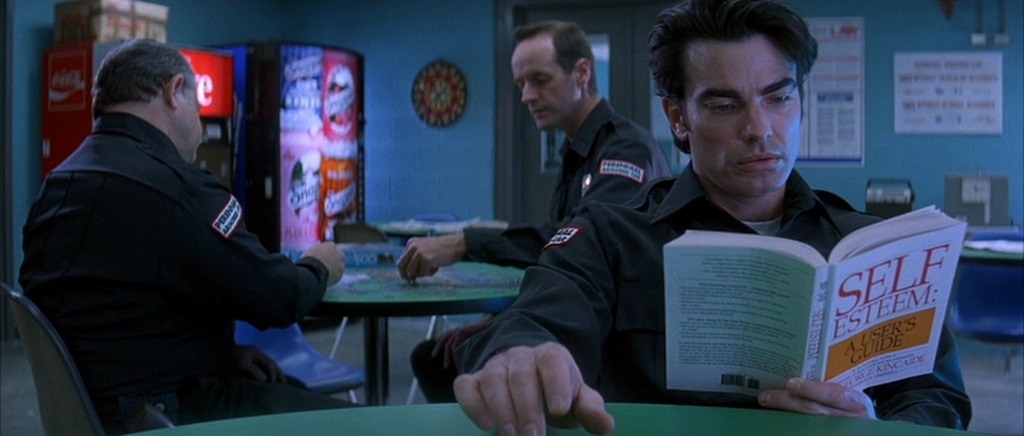

Criss Cross is a great noir film, so it naturally has a great noir look. The requisite smoke-filled rooms and moody lighting are handled with grace and beauty by cinematographer Franz Planer. It doesn’t break any rules with its photography (the one stylistic flourish is a sideways bird’s eye view of the armored car entering its destination), but damned if those rules didn’t lead to one fine-looking motion picture. I admittedly have a lot less to talk about in regards to the style than I do with Underneath, which is practically a guide on how to use every stylistic trick under the sun. Each of the film’s timelines has its own unique visual style to keep viewers informed of which timeline they’re in, with the present-day material shot with largely natural colors (with the exception of two intensely blue sequences), the flashbacks shot with a mournful blue filter, and the flash-forwards shot with a nauseating green filter, all the more effective in cinematically showing Michael’s unease and discomfort while waiting for the heist. Color filters would go onto play a large part of Soderbergh’s later work, where a shift in color means an entirely new place or time (see: Out of Sight, Traffic, Magic Mike). In addition to the green, the flash-forwards are shot entirely handheld on Ektachrome film, which creates a much coarser grain structure than the rest of the film, which is practically water-smooth in comparison. But Soderbergh (and cinematographer Elliot Davis)’s experimentation doesn’t end there. The film makes a particularly bold use of the widescreen frame, positioning actors and objects so that the screen is filled end-to-end with plot-relevant information (it must have been completely unwatchable on pan-and-scan VHS, as evidenced by the full-frame trailer included with it on the Criterion of King of the Hill). Even in his the most beautiful films he’s made since this, Soderbergh has yet to do anything like this, which makes this a particularly fascinating dead-end in his career.

The Ending

(obviously, this entails spoilers for both films)

Even in a cynical genre like film noir, Criss Cross is noteworthy for its particularly cynical ending. And yet, Underneath may out-cynical that ending with its own. The heist inevitably goes to shit, Steve/Michael’s father is shot dead, and Steve/Michael is wounded. But while the general idea of the heist sequence is the same in both, Siodmak stages it with much more flair than Soderbergh, who seems to check out while Siodmak relishes the chance to stage a failed heist that’s almost completely obscured by tear gas. In Criss Cross, Steve ends up in the hospital hailed as a hero by everyone but his best friend, who knows about what he did but is still moderately sympathetic. In Underneath, Michael also ends up in the hospital being hailed as a hero by everyone but his brother, although this sequence is made much more memorable than Siodmak’s variant as a result of Soderbergh shooting it from Michael’s woozy, bed-ridden perspective, and having the sound take the same perspective (dig how it starts fading out before the beeping of the hospital monitor wakes Michael up). In Underneath, the brother is not remotely sympathetic to Michael or his deeds, and he even encourages his fellow police officers not to guard Michael against possible intruders. In both films, there’s a suspense sequence where Steve/Michael is visited by a mysterious man who is apparently waiting for a relative in the same hospital, but whom Steve/Michael suspects is actually a hitman sent by Dundee. Both films drag out the reveal that yes, this mystery man is here to take him to Dundee, but Soderbergh drags out the suspense much further than Siodmak, who lets Steve’s suspicions fade after what he suspects is a gun in the man’s jacket is actually an address book (it’s a cell phone in Underneath). But Michael doesn’t give up so easily, pulling the old “ah ha! You were talking like you knew that person, but that person doesn’t exist!” trick, to which the man basically responds with “Yeah, I had no idea what you were talking about, I was just going along”. In Criss Cross, after Steve’s suspicions fade, we get a shot of a mirror showing the man leaving his hospital room and coming back with a wheelchair and pillow, giving the game away. But in Underneath, we don’t know if the man is trustworthy or not until right before Michael does, when the man is covering Michael’s mouth and cutting him loose. The man drives Steve/Michael to Dundee, but in Criss Cross, Steve convinces him to drive him to Anna’s place, where they can be together. Michael gets no such favors, and is sent directly to face Dundee’s gun while Rachel watches. Even though Steve and Anna get some alone time, Dundee catches up with them and shoots them both dead, while the cops come to shoot Dundee dead. That seems like it would be difficult to out-cynical, but Soderbergh does it. Technically, only Dundee dies by the end of Underneath, but things don’t look good for Michael, who’s crippled and stranded in Dundee’s home while the woman he thought was the love of his love drives away (at least Steve and Anna died in each other’s arms). Of course, things don’t look too good for Rachel either, as we find out that the extra inside man, Joe Don Baker’s boss character, is trailing right behind her, presumably to clean up loose ends. If I had to choose between getting shot by Dan Duryea while in Burt Lancaster’s arms or getting killed by Mitchell, I don’t think I’d take too long to decide.

The Acting

I haven’t mentioned the actors at many points during this. This isn’t any fault of their own (well, maybe it’s one of them’s fault), they’re mostly very good. As Steve, Burt Lancaster delivers that typical Burt Lancastery goodness, playing Steve as a bit of a lovestruck schmuck and a patsy. The way Peter Gallagher plays Michael, he’s too smart to be a patsy, but that intelligence doesn’t actually get him anywhere, and if anything, makes him look like more of an asshole (he’s not quite on the level of the irredeemable dick Gallagher plays in Soderbergh’s sex, lies, and videotape, but he’s close). Yvonne De Carlo and Allison Elliott are pretty much on equal footing with their portrayals of Anna and Rachel, respectively, nicely filling the femme fatale role. As Slim Dundee, Dan Duryea is convincing as a nasty gangster, and as Tommy Dundee, William Fichtner is convincing as an absolute creep. But while Stephen McNally does a good job with the best friend role in Criss Cross, Adam Trese is a bore and a stiff in the comparable role in Underneath, although thankfully he doesn’t have too much screentime.

The Music

You can’t go wrong with a Miklos Rozsa orchestral score, and you can’t go wrong with a moody Cliff Martinez ambient score. That’s it, that’s the section.

The Rest

Both films return frequently to the bar where Steve/Michael and Anna/Rachel hang out, and the scene where they lay eyes on each other for the first time in a while is largely the same in both films. The main difference is that Criss Cross gets Esy Morales and His Rhumba Band to lay down some tunes, The Underneath has Texas bands play like they would in an actual roadhouse (Cowboy Mouth is playing while Michael and Rachel meet again). Also, in Criss Cross, Rachel is seen dancing with a man besides Dundee when she and Steve reunite. That man is none other than Tony Curtis making a pre-fame cameo. In The Underneath, Rachel is dancing by herself when she sees Michael again, and a man smoking a cigarette is trying unsuccessfully to hit on her. That man is none other than Schizopolis‘s T. Azimuth Schwitters, alias Mike Malone (I’d call him “the guy who played T. Azimuth Schwitters” but he’s dressed exactly like Schwitters is in Schizopolis, so I count this as Schizopolis canon).

Also, that’s Elmo Oxygen himself, David Jensen as the guy who installs a satellite dish in Michael and Rachel’s backyard. And that’s Richard Linklater as the doorman to the bar where Michael and Rachel frequent.

The Final Thoughts

Ultimately, Criss Cross and The Underneath form a double-feature so interesting in its dissimilarities that neither film works as well without knowledge of the other. You need to know what kind of story Soderbergh wasn’t interested in telling to better appreciate the story he ended up telling (and telling well, regardless of what Soderbergh says about it). Also you should watch it because it’s a really good movie and so is Criss Cross, but who watches movies for anything besides auteurist reasons? Losers, that’s who.