When Nicolas Cage was announced as the star of 2014’s Left Behind it raised a few eyebrows with even his less discerning fans. Even in the (ongoing) stage of his career where straight-to-video thrillers outnumbered genuinely interesting output, the bizarrely swift reboot for a critically derided film trilogy based on a Christian book series — inexplicably directed by veteran stuntman Vic Armstrong — seemed to be scraping the barrel. For the few of us who watched it anyway, there were few surprises and certainly no pleasant ones; for those that haven’t, stick to the Simpsons parody. But the strangest thing about the whole saga is that Cage had already been “left behind” a mere five years earlier, in vastly stranger and more memorable fashion, which made the whole Left Behind affair feel a little bit like Paul McCartney joining a fifth-rate Beatles tribute act, or Peter Jackson making a second Lord of the Rings trilogy. Did the lingering appeal of Knowing cause Cage to seek out more Rapture-adjacent media to maintain his apocalyptic high? Or did he simply get another letter regarding the overdue mortgage payments on one of his castles and tell his agent to accept any and all job offers? We may never know! But let’s face it, it’s probably the latter.

But I’m getting ahead of myself – after all, Knowing takes a while to reveal its apocalyptic colors. It begins in the late 50s, as an elementary school follows the suggestion of Lucinda, their quietest, weirdest student and bury a time capsule for the Children of the Future to open. While most of the children stuff the capsule with pictures of rockets and other futuristic nonsense, Lucinda frantically fills her sheet of paper with a seemingly random string of numbers. Cut to half a century later, and who should be attending the very same school but Nicolas Cage’s son, Caleb? Cage teaches astrophysics to a bunch of geniuses (and also Liam Hemsworth) at MIT, and, like most highly respected professors of science and/or movie single dads, he is reliably late to every important event or appointment. Still, he arrives at the big school half-centenary celebration just in time to see young Caleb receive the very same piece of numeral-strewn paper from the film’s retro prologue — although he is unable to prevent one of Caleb’s school-chums mockingly pointing out that “everyone else got a picture.” Kids can be so cruel!

After this intriguing, atmospheric set-up, the film settles into the Cage-and-son domestic routine. The son has a hearing aid; the father a drinking problem. The mother is absent, which may or may not relate to the drinking problem. But as it turns out, a whiskey-drunk astrophysics-teacher-in-mourning is the best possibly hyphenated combination when there’s a strange numerical puzzle on the cards, and before the night is out, Cage has started to find patterns in the numbers. You see, these aren’t just a random string of digits — each set represents a date… and a death toll. This all gets revealed in an all-time great montage — Nicolas Cage knocking back booze, searching for disasters on the internet and spending an entire sleepless night circling numbers on a whiteboard before dragging himself out on the school run. And yet! He still has enough energy left to explain his crackpot theories to his colleague, Ben Mendelsohn (at which point it should start to become clear that literally everyone in this film apart from Cage and his movie-son is Australian, for some reason).

The idea that an unusual 50s schoolgirl may have predicted every major disaster is an unsettling one; the concept that an exhausted teacher could decipher the whole thing in one drunken evening perhaps even more so. But the real hook of the film comes from the fact that not every one of the dates in Lucinda’s list fell in the past — and now that Cage has a sort of “disaster directory,” can any of them be prevented? Or will everyone just think he’s a deranged idiot? Will this become a disaster movie? A sci-fi movie? Horror, even? Or will the visionary director Alex Proyas, as yet untainted by the Gods of Egypt backlash that not even a creepy child can predict, simply throw all of these ingredients together into one super-weird mix and stir them together?

As the next predicted date rolls around, Cage oversleeps after a night watching the 24-hour news cycle and waiting for something to explode. On the way to pick up Caleb, disaster finds him — and a plane drops from the sky. Knowing may have been working with a relatively small budget, by 2009 standards — a quarter of what 2012 had to play with, a third of Angels and Demons, and it provides a similar experience to watching them both at the same time — but in these big disaster scenes it really makes that money work. There may be a slightly dated CGI look to the plane as it smashes across the highway, but the long take of Cage desperately working to extinguish the flames and dragging people from the wreckage is visceral stuff. The second disaster packs a punch too — a derailed New York Subway train smashing through the city.

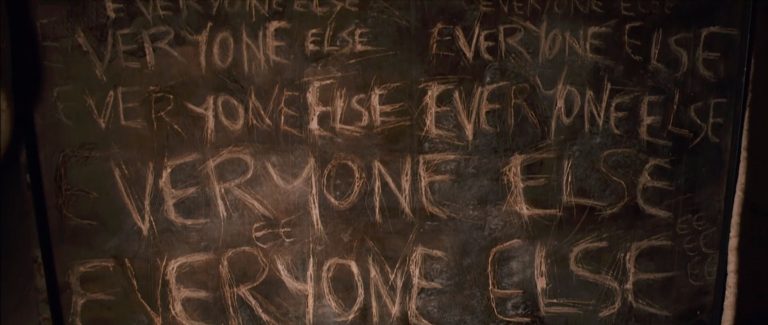

Caleb is having a strange old time, too — his dad may be keeping him sheltered from the ongoing disasters, but various strange, silent blonde men keep handing him smooth pebbles and showing him visions of Armageddon through his bedroom window. But the unusual trials and tribulations of this small, troubled family do sufficiently convert a couple of useful thinkers to their cause; firstly Mendelsohn and his analytical brain, and then Rose Byrne — daughter of the creepy school child who set this all in motion — who takes the Australian quotient to impressive new levels, and also brings along a daughter to keep Caleb out of trouble. With the team assembled, there is only one date on Lucinda’s sheet left to puzzle over. But this one lacks a death toll; it just has two letters: EE. What could this possibly mean?

Only a crack team of MIT scientists can solve this sort of puzzle — luckily, this is a resource Cage can easily assemble, and within minutes they’ve confirmed that the end really is nigh. A solar flare is heading towards the Earth, but they’d basically been assuming it would be harmless; with the additional knowledge that a child had written down a load of creepy numbers 50 years earlier, they can no longer retain their optimism. And so begin the riots, the looting, the family reconciliations. But Knowing has one more plot thread to tie up — what’s with Caleb’s creepy, silent pursuers? Could it possibly be that these menacing figures, who have been appearing in growing numbers, actually have good reasons for wanting to take two innocent children away from their parents and take them where they’ll never be seen again? I will leave the answer to this cosmic mystery in the hands of Alex Proyas and his engagingly weird, critically divisive masterwork.