As a Set of Dichotomies, a Way to Break Expectations, and a Personal Audience Identification Revelation – by Désirée I. Guzzetta

By the time I finally saw director Tobe Hooper’s classic tale of cannibalism, I had been primed to be terrified by years of hearing about the gruesome grunginess of it. Being averse to gore and slashers in general, I had studiously avoided seeing the film for fear of being traumatized by it. I was too young for R-rated films when it came out in 1974 and I’m glad my mom, who sparked my love of horror in the first place, didn’t take me to see it as she had with less-intense fare.

Even without all that build-up, though, the film would’ve scared me—although I probably would not have sat back down after jumping a mile off my couch when Leatherface (Gunnar Hansen) appears out of seeming thin air with his chainsaw to gore the annoying Franklin (Paul A. Partain) to death, laughed and clapped my hands, then delightedly asked my friend who brought his well-worn tape over if I could rewind to watch the scene again. I was both thrilled and chilled, and I wanted to experience that feeling again right away.

I’d long gotten over my fear of seeing gore, which I needn’t have worried about with Massacre because compared to other slashers, it is fairly mild. You never see the meat hook go into Pam’s (Teri McMinn) back, for example. You don’t see Kirk (William Vail) actually get dismembered. Even Franklin being repeatedly gutted is blocked from view by the hulking Leatherface. There’s blood, of course, but no viscera. It was less gory than some of the footage being broadcast into family homes during the Vietnam War, which I saw plenty of growing up (the film is a commentary on that war, among other things). Hooper has said the film was a direct response to the brutality shown as a matter of course on the nightly news. A lot of elements in the film point to the dehumanization he and many of us witnessed on our televisions back then. It was a strange dichotomy to be in a safe place (home) watching war as “entertainment.”

In Massacre, there are all sorts of dichotomies. For example, none of the cannibal family has names, but designations: Hitchhiker (Edwin Neal), Leatherface, Old Man (Jim Siedow), and Grandfather (John Dugan);they didn’t get full names until the sequel. Kirk, Jerry, and Pam at least get first names. Sally (Marilyn Burns) and Franklin are the only ones with full names (last name is Hardesty). Monsters don’t get to have names, but “real” people do, which helps the audience sympathize with them.

Another dichotomy is the two realms of the film. The family of cannibals occupy one realm, festooned with the bones and feathers and skin of all their kills. There’s a steel sliding door that cuts off the kitchen from the rest of the house. Kirk briefly glimpses several animal skulls and heads on the wall beyond the door, and is too startled to notice the ramp leading up to it — he trips on it as Leatherface suddenly appears and strikes a killing blow to Kirk’s head with a sledgehammer. Leatherface drags Kirk up the ramp into the kitchen and slams the door shut to the true horror at the heart of the film, preventing us from seeing inside. My anxiety at that moment shot up to eleven. I both wanted to know and to never know what was happening behind that gleaming silver barrier. I also knew no matter what, eventually it would open and I would find out.

The other realm is the sunny outside, the one containing Sally and her friends and their hippie lifestyle, but while we spend significant time with them in that realm before they ever meet Leatherface, we know they are doomed. John Larroquette’s narrator intones as the film opens that the tragedy of this “true story” is made all the more horrible by how young Sally and her friends are, which sets up the dark tone. Every experience they have on the way to the homestead says “turn back” but they keep plugging along. It’s masterful building of suspense, but it’s also frustrating to see the characters driving toward their gruesome deaths. The first kill doesn’t even happen until around minute 35. It’s all downhill from there.

Of course, the time in the sunny realm has unsettling oddities, such as the two desecrated and obscenely posed corpses being photographed as the film opens, or the Hitchhiker’s weird behavior in the van carrying Sally and her friends. The first violence against a living person takes place when the Hitchhiker grabs and slices open Franklin’s arm. The friends kick him out, but they continue on their way to Sally and Franklin’s old family homestead. Even a strange stop at a local gas station doesn’t deter them from blithely carrying on.

Beyond the scares and unsettling feeling, though, is a lot of torture of women, specifically of Sally, the Final Girl. The men get off relatively easy, as they are killed quickly. Pam has to hang there, slowly bleeding out while watching her boyfriend getting carved. Sally is tormented repeatedly at the cannibal family’s dinner table. This is where the film both terrified and annoyed me.

Almost 30 minutes is spent on Sally’s terror. She’s chased by Leatherface to the farmhouse and finds what she thinks are corpses in the attic (except Grandfather isn’t dead). She jumps out of a second story window to escape and becomes an injured, wounded animal. She manages to get back to the gas station to get help, only to discover that Old Man is one of the cannibals. He comforts her, then he knocks her out, ties her up, gags and bags her, and drives her straight back to Terror Town.

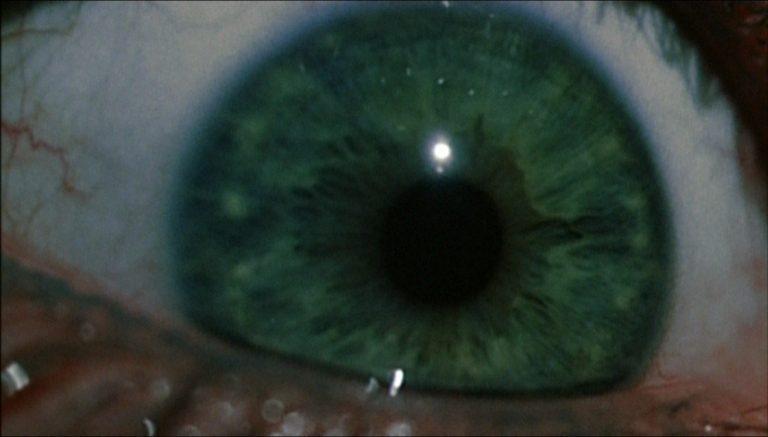

On the way, he pokes her with a broken broom handle to torture her further (and maybe tenderize her a little). He’s gleeful. It then seems like she spends the last 20 minutes of the film screaming, but it’s only about nine minutes—it just felt interminable to me. The cannibal family mocks her terror. We’re treated to close-ups and extreme close-ups on her face and eyes and her terror as they mock her tears and fears. She’s treated like meat because she is meat. “Hit that bitch!” Hitchhiker says to Grandfather. She’s less than nothing to them.

At that point, I discovered I was a bad feminist because I wanted them to kill her so she’d shut up. It says something about the grim power of the film — and that tone-setting narration of doom — that instead of rooting for her to escape, I was convinced she was a goner and I just wanted it over with. It was warped spectator identification to me, but I’ve long since read in my studies that it’s common for women watching horror to identify with the monster because we are equated with it (see: monstrous feminine and other theories outside the scope of this little review).

Fortunately, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is leavened with comedy, intentional or otherwise, a welcome respite from the gloomy proceedings. Leatherface frets after Jerry dies, his tongue lolling out of his mouth. He was surprised by Jerry’s presence and he doesn’t know how many more people might be coming. When the Old Man subdues Sally at the gas station and is about to drive her back to the homestead, he realizes he forgot to lock up and hops right back out. Grandfather is too feeble to wield a hammer and kill Sally; he keeps dropping it and Leatherface keeps putting it right back in his withered hand.

Sally finally does manage to wriggle free and jump out yet another window, Leatherface and the Hitchhiker chasing her out to the road. When the Hitchhiker catches up, he keeps slashing her back as she keeps running. Luckily for Sally, he’s hit by a semi; the driver then manages to knock Leatherface down with a flying pipe wrench, causing him to fall and drop the running chainsaw on his own leg. Another man in a pickup shows up and Sally climbs into the flatbed. They drive away as Leatherface, in impotent anger, waves the chainsaw around as the sun comes up. I felt such immense relief (and a little horror at my own earlier reaction), tempered by the fact that Leatherface, the Old Man, and Grandfather were still out there — not to mention the driver of the semi who seems to have disappeared out of frame and out of mind.

As a Work of Visual Art — by Sam “Burgundy Suit” Scott

Desiree’s right about the dark humor here — Hooper would spend most of his career much further in the camp realm, especially with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2, but you can still see it creeping into this much more earnest film. I saw the original at a theater with an audience that kept laughing at inappropriate times — I was worried it’d be like this for this the whole movie, but I shouldn’t have. The nonstop intensity stunned them silent, and by the last act — ironically, the most intentionally comedic — they were too horrified to make a sound.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is a remnant of a very different time in movie history, when cheap cameras actually made movies look cooler than their upmarket Hollywood equivalents. Nowadays, cheap digital cameras suck all the color out of low-budget films; but 16mm flooded the frame with color, refracting light into prisms as it bounced off the lens. 16mm had the same low-definition limitations as modern budget cameras; but the soft, almost organic shapes of film grains can actually enhance the image in a way that gritty, blocky pixels don’t, and there’s a certain beauty to the way they shimmer and dance as the film moves along.

Tobe Hooper and cinematographer Daniel Pearl used their tools to their advantage. Many horror films exist in a stylized, colorless world, to imitate the black-and-white classics and the way human colorvision shuts down in darkness. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre goes the exact opposite direction, emphasizing a full spectrum of color. At many points, it’s downright gorgeous; how many other horror movies set major setpieces at the “golden hour” just before dusk, or include long, Terence Malick-style shots of the beauty of the setting sun?

Despite its horror bona fides, it seems wrong to cover Massacre on Halloween — the film’s use of light and color, washed out frames and sunbaked landscapes, makes the oppressive summer atmosphere palpable on even the chilliest autumn days. Even the most horrific moments have a strange and terrible beauty — just look at the brilliant greens and reds in the extreme close-ups of Sally’s horrified eye.

The same kind of care goes into creating the environments the camera will film. The Family’s cabin is a vividly realized nightmare realm, especially when we first see it. That shot of the blood-red room standing out in the darkness of the cabin, skulls of all kinds lining the walls, clues us in that we’re very far from the safe world of the everyday. Hooper fills the house with surreal imagery, like the floor covered in chicken feathers, bones, and teeth; or the dozens of ghoulishly inventive ways he finds to repurpose body parts as furniture: a lightbulb held by a severed hand, a couch made out of bones, human faces as lampshades.

If it hadn’t come first, Massacre could seem like a meta-commentary on its many heartless and mindless imitators that treat their victims as nothing but beasts for the slaughter, and their bodies as pieces of meat. For all the care that goes into designing this house of horrors, Hooper enhances the horrors by making it appear as if no care went into it at all. These strange artifacts are all haphazardly tossed around as if the house had been left abandoned, or as if it’s still under construction: many rooms in the cabin have the appearance of a workroom in the middle of some enormous project.

As a Masterpiece of Intensity — by Jacob Klemmer

When I think of an image from The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, my mind doesn’t immediately jump to the meathooks or the mask or the dance or even Sally riding in the pickup of a truck, covered in blood, wailing in trauma. The image I think of, at about an hour and five minutes into the movie, is relatively simple: two lights, the headlights on a car, hurtling toward the camera over a black screen. It’s Old Man, pulling into the driveway in preparation for the family dinner. What strikes me most is the pure abstraction — we see only the bare minimum necessary to understand the image, but even then the shot is bombastic in its quickness, its directness, and in just how close the headlights get to the camera and how loud the car is. Yet even when they get close, they’re still out of focus.

This unremarkable shot, for me, is the skeleton key for the whole of the film, and not just because it’s the gateway into the film’s most terrorizing section — the family dinner. It crystallizes the film’s ultimate formal contrasts: intensity and abstraction, bombast and minimalism. You can see it in Leatherface’s first kill: a quick hit to the head with a hammer, far away from the frame, over as soon as it starts — thrilling in both how quickly it passes and how far away it is. You can see it in all the kills: flurries of montage, keeping all of the gore offscreen but presenting the textures of blood, dirt, and grime in such stark view that you feel as if you’re looking at gore, even if you’re looking at a wall.

In fact, most of the horror comes from the sound and not the images. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is unique in that its score doesn’t have as recognizable and iconic a melody as, say, The Exorcist or Halloween, but its sound design is even more crucial. Even as the images pull away, the sounds smother you. In the early hitchhiker scene, in the dinner scene, and in those crucial kills there is always an overabundance of sound and not a shred of quiet: shrieking, laughing, crying, radios playing country music, unintelligible arguing, motors running, and of course the unending sputtering of the chainsaw. The titular weapon is so horrific not just because of its potential for gore but because it just never shuts up. This, perhaps, is what makes that final cut to black so unnerving: it’s not the blackness that frightens us but the sudden silence. What score does appear in the film is ambient and stressful, noisy and amelodic, just as textured and non-concrete as all those shots of filthy walls and bloody floors.

All this frenetic montage, abstraction, heightening of textures and lack of true narrative captures the feeling of a waking nightmare. The film passes from day to night and day again, and never is there a wink of sleep: it is perversely continuous and uncompromising, even as it doesn’t really show you very much. “Your mind fills in the gaps” has become a cliché when talking about horror films that, frankly, just don’t deliver the goods. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre comes at you as quickly and intensely as those headlights, freaking you out while beckoning you to come in; like an invitation to the most fucked up dinner party of your life. Most horror films dare you to look away. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre dares you to look closer.