I’ve got wild, staring eyes.

And I got a strong urge to fly.

But I got

Nowhere to fly to

Fly to

Fly to…

Where we came into an album can affect how we view it. I first* discovered Pink Floyd’s The Wall after loading up a CD carrier with albums at a garage sale in the summer of 2016. At the time, I was mostly thinking about the deal – a couple dozen CDs for ten dollars, and that was mostly to cover the cost of the carrier. But once I popped this specific album into my car’s player, it was the start of an obsession that would last most of the next year.

It’s certainly an album that invites obsession, in all its musical and lyrical complexities. But at the same time, it probably shouldn’t have been — not just because of all the trials and tribulations that went into its making, but because the entire concept seems so unlikely. We’d seen plenty of bombastic rock operas by 1979, but The Wall’s noticeably light on epic struggles between good and evil on a dramatic backdrop of magical lands or the endless vastness of space. In fact, most of the album takes place in a single hotel room, even if it is “bigger than my whole apartment” as the groupie describes it. Heck, the beginning is a more dramatic version of the old cliché, “Yep, that’s me. You’re probably wondering how I got into this situation…” If you own The Wall on vinyl, you can scratch your needle to get the full effect.

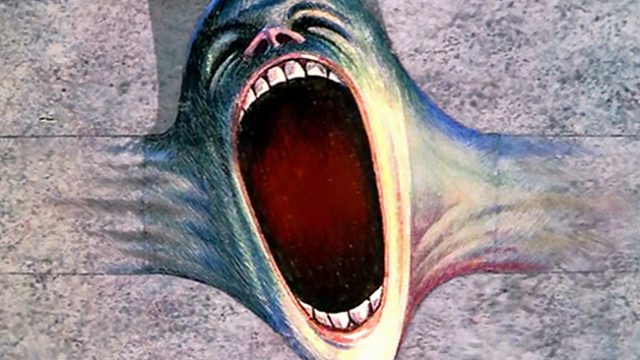

From there, though, we get sonically yanked back into the past by the sound of the entire band banging on their instruments and a diving fighter plane (and yes, Pink Floyd actually brought one out onstage – predictably, it started a fire at least once, which the fans assumed was all part of the show) transitioning into the narrator, Pink’s first cry. Recreating film language in a medium without visuals (“Lights! Roll the sound effects! Action!”), Pink Floyd ended up creating an effect more cinematic than any actual movie.

From there, The Wall sits its narrator down on the couch to review his formative experiences, the traumas of the loss of his father to the war, the horrors of the Blitz, and his abusive schooling in “Another Brick in the Wall Pt. 2,” the big hit single for a band that didn’t do singles and certainly didn’t try to make them hits. After the fury of that track, Roger Waters audibly takes a deep breath to prepare himself for the next one, “Mother.” At first, it seems like the song itself will be a breather, with the soft strumming of folkie guitar. And “Mother” is, like “Comfortably Numb” and “Goodbye, Blue Sky” a work of incredible beauty. But The Wall always sounds the most beautiful when it gets the ugliest. Nestled in the comforting melodies, the song shows the beginning of Pink’s descent into evil, with Mother raising him into the cold, callous creature we see for the rest of the album. The best example of this approach is when Waters sings “Hush now, baby, baby/Don’t you cry/Mama’s gonna make all of your nightmares come true,” substituting the word “nightmares” for “dreams” with such a barely perceptible change of tone that I must have listened to it five or ten times before I could stop doing a double take whenever I heard it. (He pulls off the same trick to equally chilling effect later in the album – on “In the Flesh,” he calls out “All there any queers in the theater tonight?” holds for applause, and then calmly adds, “Put ‘em up against the wall.”) Chilling subtlety is the hallmark of the album, and here it is again, with the soft, trembling delivery of, “Mother, did it need to be so/High?” followed up immediately with a child innocently saying, “Look, mummy, there’s an airplane up in the sky” that turns out to be an Axis bomber.

We check in on Pink as an adult, now a rock star, but one less like his namesake and more like their cock rock competitors, as parodied by David Gilmour’s meathead holler on “Young Lust.” The lyrics show Pink cruising for “a dirty woman,” but when he calls his wife and finds another man on the line, he frighteningly and totally snaps. There’s a heavy sense of dread over “One of My Turns” even before Pink lets loose: under the heavy levels of reverb and instrumental drone, the groupie’s intonation of “wanna take a baaaaath?” sounds less like a come-on and more like a threat. When he does let loose, it only becomes more horrifying, as he suddenly jumps from depressive to game-show-announcer manic (if this had come out a few decades later, I’d call it a pitch-perfect parody of MTV’s Cribs). Pink Floyd’s career-long experiments with musique concrete sound effects pay off here, with the sounds of violence crashing over Water’s vocals. It’s the rock-star fantasy of trashing a hotel room recast as horror, Floyd switching out “nightmare” for “dream” at the last second again. We see the narrator revealed as a monster, but like all the great monsters he inspires pity as well as fear. The lines “Would you like to learn to fly?/Would you?/Would you like to see me try?” develop an image of entrapment Waters introduced in “Mother’ (“Mama’s gonna keep baby under her wing/She won’t let you fly, but she might let you sing”) and that he’ll return to later. And in the song’s last lines, he transforms what seems like a joke on paper into something deeply haunting as his voice echoes and all other sounds drop out:

Would you like to call the cops?

Do you think it’s time I stopped?

Why are you running away?

It only gets darker from there. “Don’t Leave Me Now” is a blast of equally potent sadness and horror, as Pink tearfully begs his absent wife to comfort him while also revealing in the most shocking ways that he’s responsible for his own isolation:

Oh, babe,

Don’t leave me now.

I need you.

To beat to a pulp on a Saturday night.

Pink Floyd has been accused of pretension, and by no means wrongly, either.** But it takes a real humility to make yourself look this bad, not just to draw such a deeply loathsome character from your own personality, but to inhabit him with such raw emotion it pushes your voice past its limits, leaving only an awkward, off-key squawk. It could have been comic, and it’s all the more tragic for that. As I mentioned in my last Pink Floyd review, you’d think a prog rock monster like them would be antithetical to the punk movement — remember that live show with the giant friggin’ airplane? But The Wall has a surprisingly punk attitude, not just in the antiauthoritarian viewpoint of tracks like “Another Brick, Pt. 2,” but in the DIY disdain for conventional ideas of beauty and professionalism in Waters’ vocals here. Who knows? Maybe that’s why punk rocker Bob Geldoff was able to overcome his contempt for the album as “overblown and old hat social-conscience -stricken-millionaire leftism” and play Pink in the movie.

Waters has credited his own wife for saving him from becoming Pink, but the stories from behind the scenes of the album make you wonder how successful he was. His singular, tyrannical vision led him to violently clash with his collaborators and attempt to take sole credit for The Wall and mark it as “A Roger Waters album with music by Pink Floyd.” (There’s a reason I’ve been crediting all the artistic choices to Pink Floyd. Even if it’s not strictly accurate, I’d rather not give Waters the satisfaction.) He succeeded in taking keyboardist Richard Wright and drummer Nick Mason’s names off the record — Mason would have his credit restored on the second pressing, but Wright would be gone entirely by their next album. “Don’t Leave Me Now” shows how misguided that decision was – David Gilmour’s screaming guitar gives the repetition of the lyric “Why are you running away?” from the previous track far more power than it ever could have had on its own. That said, the nonmusical elements of the track are equally important, as the changing channels on the television begin to bleed into each other, building to a crazy-making din that finally climaxes with Waters’ guttural scream as he smashes the set. The chaos settles into the deliberate, military march of “Another Brick in the Wall, Pt. 3” as Pink sets in the final brick, declaring “I don’t need no arms around me/I don’t need no drugs to calm me.”

For all the improbability of setting a grandiose rock opera in an empty hotel room, this section is really the centerpiece of the album — not just because it sits square in the middle, but because it’s where The Wall reaches the height of its sad, lonely, horrible power. “Hey You” has Waters and Gilmour pouring their soul into the narrator’s desperate howl for help, with all the musical bombast only increasing its frightening intimacy. While The Wall draws from the modernist tradition of isolation narratives like Invisible Man and Taxi Driver, it fits equally well into the classical tragedy, and an omniscient narrator briefly pokes his head in for a good dose of tragic fatalism

But in the end it was only fantasy.

The wall was too high, he could not break free,

And the worms ate into his brain

While it’s not a song in a traditional sense (two repetitions of the title make up the entirety of the lyrics), “Is There Anybody Out There?” is still essential to the record, shrouding those five words in echo and a creepy mind’s-ear soundscape to deepen the nightmare atmosphere. If Pink Floyd drew from punk, they were equally willing to straddle the line with its musical antithesis, and the lush orchestra of “Nobody Home” is every bit as powerful as “Don’t Leave Me Now”’s ragged minimalism. “Bring the Boys Back Home” is worth a mention too, as one of the few areas the movie actually improves on its source material. The mock-opera chorale’s more than a little overblown, but what’s silly on record is shatteringly powerful on film, with every one of those voices looking intently into your eyes as you watch. If the minute-and-a-half interludes of “Boys” and “Vera” are a little thin, that’s because they’re just a warm-up for “Comfortably Numb,” possibly the greatest song in the whole suite. While it doesn’t hit me as hard personally as some of the others, that’s more from familiarity than anything else — I’ve heard it on the radio many times even above dozens of times I’ve spun the album as a whole. What’s undeniable is the tragic beauty of the imagery and the looping, Philip-Glassesque strings. At this point in Pink’s delirium, past and present are merging into each other: the shouts of his manager literally echo with the abuse of the schoolmaster, and the call of “Is anybody out there” is ironically flipped as the manager asked “Is there anybody in there?” before pumping Pink full of enough drugs to wake him up. As much as Pink comes from Waters’ psyche, this track gains much of its heartbreaking power from its resonance with Pink Floyd’s founder, Syd Barrett, who never came out of his drug-induced haze.

If the drugs were meant to keep Pink docile and controllable, they fail miserably. In “In the Flesh,” he marches out onstage and turns his rock concert into a fascist rally. I probably don’t need to underline the reasons an entertainer leading a grassroots authoritarian movement can seem a little too familiar to the modern world. That said, other recent events and other grassroots movements have soured my old my worshipful view of the album. For instance, the two years since I first heard The Wall have seen terrorist attacks by “incels,” disaffected young white men much like Pink who claim their loneliness and isolation justify their atrocities. My admiration for Pink Floyd’s ability to find empathy for their monstrous antihero is lessened now that I’ve seen that as long as these lonely young men have the right skin color, they find no shortage of empathy from a media that thinks they should be given license to rape to keep them happy. So much great art finds the humanity in the very worst straight white men, but does that have the same value when we seem to be the baseline for humanity in our culture’s mind to begin with? What does it say when we seem to have as many works empathizing with them as every other demographic combined, good or bad? Empathy for a racist misogynist no longer seems as radical when you’ve seen all the ways society privileges these men above their victims. What are the implications of siding with Pink after we see his violence against women and stoking of racial hatred? Or of portraying a fascist as the victim and not the people he’s victimized? What does it mean to be asked to feel the pain of a man who believes you’re subhuman? The movie shows him leading his followers to acts of rape and murder (though in the movie, even more than the album, it’s never quite clear what’s inside and outside Pink’s head) — doesn’t it take a little more than a dream trial to redeem him from that, if he is redeemed? These are questions I can’t answer, but it seems dishonest not to raise them.

Waters may have been too close to Pink (last name Floyd) to walk the empathy-without-sympathy tightrope of something like Taxi Driver. That said, he does seem to recognize the fraught territory he’s working in. “Don’t Leave Me Now” contrasts Pink’s self-pity against the violence that’s the real cause of his troubles. With the line “I’ve got a silver spoon on a chain,” Pink Floyd suggests privilege can be its own prison, and we can certainly see how it has further warped Pink’s psyche — doesn’t the first side describe how the wall was built from good schooling, an attentive mother, and heights of fame and fortune? (While they’d almost certainly get the wrong message, I feel like the incels need to listen to this album just so they can see that even having superhuman amounts of sex can’t cure the real heart of loneliness.) The expanded movie version of “Empty Spaces” develops this idea further against Gerald Scarfe’s animated backdrop of a wall made of luxurious possessions:

Shall we buy a new guitar?

Shall we drive a more powerful car?…

Fill the attic with cash,

Bury treasure,

Store up leisure,

But never relax at all

With our backs to the wall.

However eager Pink Floyd is to absolve their namesake of responsibility for his demagoguery, they don’t shy away from the horror of it. The martial percussion works things up to a fever pitch, while incongruous poppy elements — backing lyrics by Bruce Johnston of The Beach Boys and Toni Tennille of The Captain and…, disco synths on “Run Like Hell” – only make it more horrible. There’s imagery of a complete break from the self – “Pink isn’t well/He stayed back at the hotel” – and rhetoric taken from real world fascists. Most frightening of all is “Waiting for the Worms,” opening with a TV-Nazi cackle of “Ein! Zwei! Drei! Ha!” From there, Beach Boys-style harmonizing sits uneasily next to promises of a new British Empire, threats threats of a new Holocaust, slurs, an unintelligible voice barking orders over a megaphone, and the insistent, pulsing repetition of the two syllables “wai-ting.” That harmonizing fits into the album’s pattern of making the ugliest moments sound prettiest in the first lines, as Pink makes it clear that the man we knew did indeed stay back in the hotel:

Ooh-ooh

You cannot reach me now.

Ooh-ooh

No matter how you try.

Goodbye, cruel world, it’s over.

Walk on by.

The violence builds to greater and greater intensity as the song goes on, not slowing down as it comes back from the harmonic interludes. The chant of “wai-ting” is replaced with shouts of “ham-mer!” the intensity continuing to build until it reaches its peak and a conscience-stricken Pink cuts it off, screaming for the chaos to stop.

Roger Waters once said about the director of The Wall’s film adaptation, “I once had a very heated conversation with Alan Parker where he said to me that the perfect film is made up of one hundred perfect minutes. That, to me seems to be wrong. There’s got to be lots and lots of imperfect minutes to make a perfect hundred.” That sums up The Wall’s musical incarnation. It explains the use of false notes and “bad” singing to convey emotional rawness. It explains the structure, more like a true opera than a conventional album, with many tracks functioning less as independent songs than developing musical and philosophical themes from earlier on the record to make a whole greater than the sum of the parts. And it explains how I can forgive The Wall for faltering at the crucial moment. The Wall promises an epic, but in its climax, “The Trial” can only deliver camp. But if Pink Floyd could live up to their ambitions, we couldn’t believe they were high enough, and so the imperfection of “The Trial” doesn’t detract from the perfection of The Wall. And make no mistake, it is imperfect. At the story’s most serious point, Pink Floyd retreats into scatological humor and silly voices (without making it any easier to distinguish the characters). This is where the band loses control of their symbology as well — the track is supposed to represent Pink opening up to his own feelings and the people around him, but they’re all shown as hateful monsters, and the Judge, in a line Waters deliciously sinks his teeth into, accuses Pink of “showing feelings/Showing feelings of an almost human nature” and punishes him by tearing down the very wall that kept those feelings out. But there’s still moments of real power there – the wordplay of “They must have taken my marbles away” heartbreakingly sums up Pink’s combination of insanity and helplessness.

It’s also where the narrator’s misogyny reaches its nastiest extremes, and the narrative is so far up his head it ends up reflecting on his creators as well. Pink imagines himself as a victim of the oppressive women in his life, and even the male characters are feminized — in Scarfe’s animation, the schoolmaster isn’t the real enemy, but rather his “fat and psychopathic wife” who works him like a marionette, and the Judge wears women’s heels and stockings under his robes. (The only other female characters on the album, the groupies, don’t exactly show an overabundance of respect for womanhood either.) At least, that’s what I thought until I gave the final track a closer listen.

The ones who really love you

Walk up and down

Outside the wall…

And when they’ve given you their all

Some stagger and fall.

After all,

It’s not easy

Banging your heart against some mad bugger’s wall.

So the omniscient narrator returns to show us the perspective of characters we’ve just seen literally demonized, putting the blame for the narrator’s crimes back on him. But is it too little, too late? It’s an almost inaudibly quiet track after the bombast of “The Trial,” and with almost unintelligibly mixed lyrics — in all the listens I gave The Wall, I only caught them as the end credits rolled on the movie.

Either way, it seems like a happy ending, but the careful listeners are rewarded — or is it punished? — with yet another twist. There’s a few other words hidden after the last lines: “Isn’t this…” And if you put the first disc on again, you hear the rest: “where we came in?” Pink’s sickness is cyclical, and he could be due for another “one of his turns” even after he demolished the wall. As I mentioned in my previous Pink Floyd review, they loved this sort of thing: the ending of the last track of Dark Side of the Moon bleeds into the opening of the first, Animals and Wish You Were Here are bookended by the beginning and end of a song suite, and The Final Cut by news reports before and after the apocalypse. They broke up before they could apply this trick to the effortless looping of CDs, but maybe that wouldn’t have appealed to their love of the esoteric. But even at their most esoteric, in concept albums based on Orwellian animal symbolism, in music made from ticking clocks and wine glasses, or overstuffed rock operas about bricks and worms, they could still speak past the intellect direct to the heart to make works of great emotional power.

Isn’t this?

* When I say “first,” I only mean that my attempt to watch the movie years earlier gets disqualified on a technicality – the copy I had checked out from my local video store was so beat up that what felt like half of it was unplayable. More recently, at another garage sale, I found it again and got excited that I’d finally get a chance to watch it all the way through. The other night, I opened it up, only to find it was the exact same copy I couldn’t play before.

I think this is what’s known as a small town problem.

** I once played The Wall while driving my dad to the airport and asked if he had ever listened to Pink Floyd when he was my age. “No,” he said. “I guess I never took them seriously.” I told him that was alright. They took themselves seriously enough for both of them.