“The Trial is the best film I have ever made.” – Orson Welles

That’s a bold statement coming from Welles, who, after all, also directed Citizen Kane, widely considered the Citizen Kane of movies. But watching The Trial, it’s easy to see why he’d make it. Even in Welles’ career, there are few movies like The Trial. Working on a production so cheap his producers couldn’t even afford their hotel rooms, filming in abandoned and empty buildings, including the enormous Parisian train station that would later become the Musee D’Orsay, Welles created an entire, alien world in a way that enormous Hollywood epics struggle to. The Trial exists in a postwar Europe that seems to be not just decaying, but dying like a living thing. The courts are made of moldering plywood, and K’s apartment sits in the middle of a barren wasteland; even the towering office buildings are full of shattered windows.

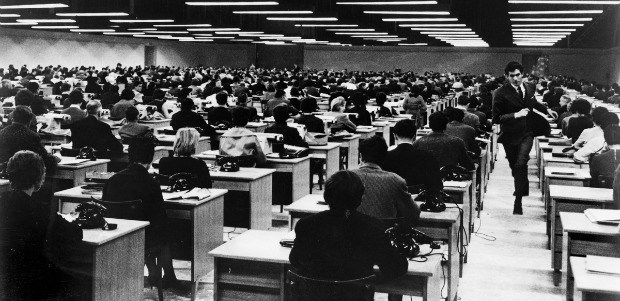

To represent the oppression of The Trial’s world Welles departed from the “cramped” setting a participant in Welles’ University of Southern California Q&A found in Kafka’s novel. If the book was claustrophobic, the film’s cavernous train-station sets are agoraphobic, dwarfing Anthony Perkins into insignificance just as his character, Josef K., is insignificant in the eyes of his world’s sprawling bureaucracy. The spaces of The Trial are horrifying not just in their hugeness but in their emptiness, visualizing the script’s sense of a world empty of hope and meaning. It’s been said you never saw a ceiling on film before Citizen Kane, and The Trial continues that tradition in Welles’ work. It seems like we’re always looking at ceilings here, alternately looming and falling apart.

The version of The Trial I watched opens with a long title card in French that I didn’t even try to read. Welles’ own introduction following the fable of the man before the law says everything you need to know to watch the movie much more succinctly: “This tale is told during the story called The Trial. It’s been said that the logic of this story is the logic of a dream… a nightmare.” It’s fitting then, that as we transition to the main story we see K, like the hero of Kafka’s other great novel, The Metamorphosis, “awaking one morning from uneasy dreams.” One of the first thing he sees this morning is a trio of policemen who tell him he’s under arrest, but won’t tell him why. Welles himself plays the Advocate, a satanic tempter who leads K to despair from his sickbed. So if the movie is a nightmare, it’s a prophetic nightmare of the kind of police states that would take over Kafka’s homeland, first during World War II and then following it, and Welles’ update draws heavily from these images. The Trial explores the ways Kafka’s nightmares have become reality, adding a scene with one of the era’s primitive computers that wouldn’t have been out of place in the original novel and, like The Crowd and The Apartment before it, imagining the modern office as a Kafkaesque place of drudgery and conformity with identical desks stretching out to infinity under chilling fluorescent lights.

We’ve talked about Welles’ agoraphobia, but The Trial can be just as claustrophobic as its source material. Most memorably, we have the scene where K finds a closet in his office building that, with the spatial logic of dreams, is also the Court’s interrogation room. After the officers had threatened him and demanded bribes, he made his own threat to denounce them before the Court, and casually does so at his first hearing. Then he finds out that he’s accidentally sentenced the officers to flogging, and if that sounds uncomfortable, the cinematography makes it even worse. The space is so tight that the flogger is constantly upsetting the lightbulb that hangs from the ceiling and sending strobes everywhere. And the camera makes the space feel even smaller, constantly pushed right in the actors’ faces, so that they weave in and out of frame with every small movement they make. And there’s a lot of movement here: the scene isn’t just claustrophobic, it’s violent, with officers constantly ducking their superior’s belt, and the edits taking the form of the quick, disjointed cuts the French New Wave had pioneered just a few years earlier.

We’ve talked about Welles’ agoraphobia, but The Trial can be just as claustrophobic as its source material. Most memorably, we have the scene where K finds a closet in his office building that, with the spatial logic of dreams, is also the Court’s interrogation room. After the officers had threatened him and demanded bribes, he made his own threat to denounce them before the Court, and casually does so at his first hearing. Then he finds out that he’s accidentally sentenced the officers to flogging, and if that sounds uncomfortable, the cinematography makes it even worse. The space is so tight that the flogger is constantly upsetting the lightbulb that hangs from the ceiling and sending strobes everywhere. And the camera makes the space feel even smaller, constantly pushed right in the actors’ faces, so that they weave in and out of frame with every small movement they make. And there’s a lot of movement here: the scene isn’t just claustrophobic, it’s violent, with officers constantly ducking their superior’s belt, and the edits taking the form of the quick, disjointed cuts the French New Wave had pioneered just a few years earlier.

If the closet seems like a surprisingly shabby place for an organization as grand as the Court, its more official venues are no better. The courtroom is cobbled together on rickety stilts, seeming, like the buildings of The Nightmare Before Christmas like it could topple over any moment.

The portrait painter’s house is made out of nothing but these slats, so haphazardly that eyes can peer in from every direction, raised above industrial machinery like a Nightmare treehouse.

The Advocate’s house seems to have a room given over for a garbage dump, and when his nurse breaks a mirror to get K’s attention, it’s doubtful anyone will notice. I’ve described The Trial’s world as decaying, but you could just as easily call it post-apocalyptic, most frighteningly in the pit where K is taken to be executed, which could just as easily be a bombed-out crater. And after two World Wars, maybe that’s the most realistic thing about it.

The score combines classical and jazz elements, and the filmmaking itself sometimes resembles a kind of visual jazz. That’s what Welles’ New Wave contemporaries were doing across town from the Orsay station, after all, and Welles may have been an Old Hollywood veteran, but he wasn’t such an old fogey he couldn’t keep up (in fact, looking at some of his earlier films, maybe the New Wavers were just then catching up with him.) When K visits the painter, we see his distracted gaze constantly flitting to the disembodied eyes watching him through the gaps in the slats. There’s another frantic scene where K tries to keep up a conversation with a court clerk as her husband carries her away, hidden and then revealed again as they run in and out of the courtroom’s barriers.

This clerk is one of many women to throw themselves at K, a touch from the novel that captures a uniquely surreal kind of eroticism. Anthony Perkins uses his long-rumored homosexuality to deepen the strangeness, constantly having to insist to these gorgeous women that he really does find them attractive even as their flirtations keep him from work that can mean his life or death to him. And in the shadow of Holocaust-era persecution of the gay community and the more recent “Pink Scare” in Welles and Perkin’s homeland, the events of The Trial take on an added resonance.

Though K lives in a dream world, he reacts as a waking man, and a major part of The Trial’s truly Kafkaesque horror comes from his helplessness as reality is being unwritten from under him. The entire premise has him accused of a crime he not only never committed but is completely unaware of. Every word and action he uses to protest his innocence is turned against him. When he corrects the inspectors on their use of the nonsense phrase “ovular shape,” he’s accused of denying the ovular shape exists at all, and the inspector mocks him for using the word when he reviews his notes as if it were his own. After he explains why he doesn’t want to get dressed in the hall, another inspector materializes and accusatorily asks him why he wants to get dressed in the hall. And when K explains why that’s the exact opposite of what he just said, the inspector moves the goalposts again: “I don’t see what you want to get all dressed up for anyway. You’re not going nowhere. You’re under arrest.” When he apologizes to his neighbor (New Wave star Jeanne Moreau) for his officemates disrupting her photographs, she doesn’t even notice until she turns around and accuses him of messing with them. The audience at his first hearing applauds and laughs apparently at random, seeming to side with him before turning on him for no apparent reason.

Roger Ebert says“The world of the movie is like a nightmare, with its hero popping from one surrealistic situation to another. Water towers open into file rooms, a woman does laundry while through the door a trial is under way, and huge trunks are dragged across empty landscapes and then back again.” The nightmare atmosphere reaches the peak of its effectiveness in the climax, at least as good as anything in the works of David Lynch. About to pass out from the heat in the painter’s stuffy room, K tries to escape as the artist keeps pushing more canvases on him, and leaves through the backroom (of what, let’s remember, is a small, raised shack) into the offices of the Court he’d seen earlier. The shabby, handmade room sits incongruously next to the cold, fluorescent-lit office, adding to the surrealism. He flees into the most simply effective of the film’s sets, a tunnel made of those same unsteady slats, as a crowd of girls chase him, the white light striping through the gaps in the black boards to create an almost abstract scene.

Somehow this leads to another tunnel, this one concrete and subterranean in a tribute to Welles’ old collaborator Carol Reed and The Third Man, but this time more like an ancient catacomb than a modern sewer.

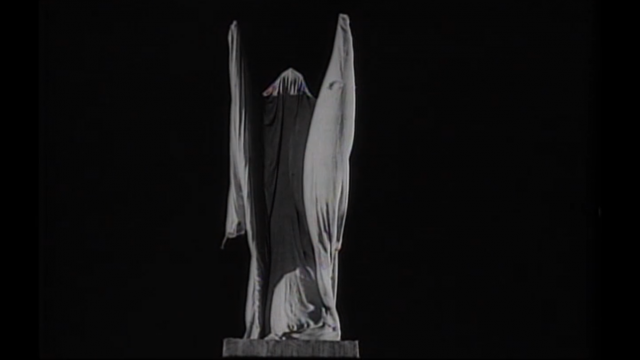

K finally stops in a huge, churchlike room, its Medieval designs clashing with its industrial steel-and-rivet supports. This is a pure dream scenario: running from an enemy even though there’s no indication of what it will do, only that it’s something horrible. But the visuals are just as important, near-total darkness like a half-awake dream where you can still see the darkness of your own eyelids. The Advocate returns, somehow no longer sick, almost entirely invisible in the shadows.

This sequence is the best argument for Welles’ assessment of the movie as his best. What follows is more controversial, as two agents of the court drag K off to the pit to execute him. Just as in the book, they pass the knife back and forth and K realizes that they want him to do the deed himself. But instead of “dying like a dog,” the movie K refuses to go gently, crowing at the agents’ cowardice as they leave him until they toss a hand grenade into the hole. The film ends with an enormous, fiery explosion – the farthest thing from the subtle, creeping horror of Kafka (the fact that K’s chosen insult is “dummies” doesn’t make it any easier to take it seriously). When asked about his decision to change the ending at the Q&A, Welles responds, “Because the book was written before the Holocaust” — and the room goes so silent you can feel it. He goes on: “and I couldn’t bear the defeat of K in the book after the Holocaust. I am not Jewish, but we are all Jewish since the Holocaust. And I couldn’t bear for him to submit to death as he does in Kafka — masochistically submit to death. It stank of the old Prague ghetto to me, and I had to let him, I had to let him shout out defiance until he was blown up.” Hopefully he isn’t claiming the victims of the Holocaust submitted — but his words are consistent with the way the period between the completion of the book and its adaptation shaped the film. Certainly, Welles doesn’t shy away from Holocaust imagery: just look at the haggard, nude figures K meets on the way to his first hearing.

As near as I can tell, Welles’ point is that now that the horrors Kafka imagined have become reality, the idea of submission to them has become too horrible to contemplate; that the film cannot, in good conscience, model any behavior through its protagonist but resistance, futile though it is. K was already defiant in the book, but Perkins emphasizes that aspect of the character throughout, pushing against the world’s injustice even to his own destruction, his scrawny physicality and reedy voice only emphasizing his impotent rage.

If the ending is too bombastic for what came before it, the epilogue is a perfectly subtle, melancholy touch. There’s a freeze frame of the smoke rising from K’s grave, letting his death sink in, as Orson Welles softly reads the names of the cast and crew. As we transition to the Advocate’s flickering slides, he concludes, simply, “I wrote and directed it. My name is Orson Welles.” He has said that the reason he chose The Trial over his other films is it was the only one he had total creative control over. After decades of studios mangling his work, this is his own act of quiet defiance. And if there’s a note of pride, after making such a masterpiece, he’s earned it.