The idea is to make the best animated film that has ever been made – there really is no reason why not. – Richard Williams

If Williams didn’t create the best animated film that has ever been made, it’s entirely possible it’s the best-animated film that has ever been made. And if you’re unwilling to grant even that, it’s still difficult to deny that no one else in the medium’s history animates quite like he does. The majority of animation is done by what’s called the “limited” technique – a single drawing is repeated across several feet of film, with only the moving parts being redrawn. The cheaper an animation is, the fewer pieces are drawn from scratch every frame. In The Thief and the Cobbler, every piece is a moving piece: every blade of grass, every face in the crowd, every fold of the Thief’s cloak. Even Disney looks shabby next to this. In a very literal sense, Williams’ studio was doing twice the work of the average animator: while most cartoons only include twelve frames per second, Williams’ packs in twenty-four, the most a filmstrip can hold. Even in his TV commercials, a form of artistic expression somewhere around prison architecture in respectability, that same obsessive extravagance is present.

Sometimes, the approach is almost suicidal in its ambition: where Williams plans to have Judge Doom attended by seven weasels and a vulture in Who Framed Roger Rabbit were shot down due to the astronomical cost of animating all of them, the titular thief here is accompanied at all times by dozens of constantly-moving flies.If this doesn’t already sound like one of the truest labors of love film has to offer, consider that it was put together over thirty years in his studio’s spare time. The working title was The Thief Who Never Gave Up, and that applies to its creators as much as any of the characters. Williams accomplishes things by hand here that it would take Disney thousands of dollars of technological development to achieve. Just compare the CGI tunnel chase from Aladdin, released the same year (more on that later) with anything here. Disney had to sink all that money and technology just to make a minute-long scene work in three dimensions. Williams made a whole film that did the same thing with just pen, paper, and paint, and I’ll give you three guesses which one has aged better.

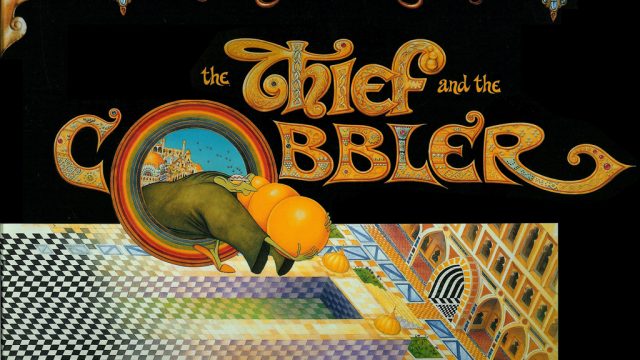

The plot’s barely even an excuse to hang the animation on, but for everyone who hasn’t seen it, it goes like this: the title characters are two Chaplinesque silent clowns, a heroic but penniless cobbler named Tack, and a superhumanly persistent thief, who picks his own pocket and steals the film itself at the end. They live in the Golden City, a utopian Orientalist metropolis climbing up an island in the middle of an oasis surrounded by a vast desert. The city remains in peace and prosperity because of the three enchanted golden balls that protect it from the highest minaret. The Thief, of course, decides to go after them, leading them to fall into the hands of the evil vizier Zigzag, voiced in an exuberant posthumous performance by a rhyme-talking Vincent Price. As if this weren’t enough, all this happens just as the king receives the news that the ferocious One-Eyes (who make up for with teeth what they lack in eyes – each of their mouths is filled with five or six rows of the things) are about to invade. So, the Princess Yum Yum, who has fallen in love with Tack, takes him and her Popeye-ish nurse to go seek the advice of a witch in the desert.

That’s not really what it’s about, though – most of what I’ve just described doesn’t even happen until the movie’s already half over. It’s just a frame to hang the Looney Tunes chases and John Ford vistas that Williams really wanted to create. Some scenes exist for no purpose at all other than pure spectacle, like one of two roses dancing in the princess’ hands, one yellow and one blue (and, if as Twin Peaks tells us, a blue rose is something not found in nature, what of a blue rose with white stars?). Each one is painted with all the detail and texture of a Vermeer painting, the petals opening and closing every moment. As for why Williams decided that such a bare-bones Arabian Nights fantasy was worth the blood, sweat, and tears that went into it, some of it might be Williams’ fascination with the Middle Eastern art he so lovingly weaves all through the movie’s world. But a more likely explanation might be in the way the region has enriched the English vocabulary with the word “arabesque,” used to describe the complex and the ornamental. Because no one in The Thief and the Cobbler, in front of or behind the camera, does anything simply. Zig Zag apparently feels that taking the stairs would be beneath him, instead launching himself from the dungeon through the palace floor by way of hundred of pulleys and springs. The witch makes her way to the pit of oracular fumes by jumping off a trampoline and swinging across the mountain by a vine like Tarzan before finally landing two feet from where she started. And then there’s the One-Eye’s war machine, a dizzying array of sledgehammers, spring-loaded traps, and enormous crossbows, so huge that it uses elephants as ammunition. Like any Rube Goldberg machine, every piece needs to be in place for it to work, and a single tack causes the whole thing to fall apart in the climactic battle. That machine ultimately serves as an apt metaphor for the movie: awe-inspiringly intricate, but finally destroyed by its own complexity.

After the success of Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Richard Williams finally got the funding to complete his life’s work and took his two and a half hours of completed pencil animation to Warner Brothers. Expecting anyone who would redraw every heart and club on a full fifty-two card deck twenty-four times a second to play fair by studio bean-counters was, of course, a colossal mistake. This wasn’t even the first time he’d gone over-budget on a feature film: the bottom fell out of the only other one he ever directed, Raggedy Ann and Andy (and it is not difficult to tell which scenes were animated before he ran out of money and which were completed after). Even Who Framed Roger Rabbit burned through its animation budget before completion, leading to the scenes in Toontown featuring less spectacular animation, a lot of it spliced in from earlier films.

Even then, the mishandling of The Thief and the Cobbler is horribly cruel. After three years at Warners’ – which, as a reminder, only makes up ten percent of the film’s overall productions – failed to produce a completed product, the backers panicked. Disney, itself an enormous war machine, had its own Arabian Nights fantasy ready for release, and if The Thief couldn’t beat it into theaters, it would either be ignored or dismissed as a knockoff. The truth, of course, was the knocking off went the other way. True, it’s no surprise that two stories in the same genre would feature a scrappy hero, a white-robed sultan and an evil grand vizier, but it’s more than a little suspicious when both viziers have a tormented bird sidekick and the exact same beard. Disney’s war machine might have sunk The Thief’s chances no matter what, though. When work began in the late sixties, Disney’s waning success left a power vacuum in the animation world, one where shaggy, experimental films like Fritz the Cat, Yellow Submarine, and Watership Down could thrive. But now that the Mouse was the top dog again (made possible, with cruel irony, by Williams’ work on Roger Rabbit), there was little room for competition, and even less so for films that didn’t try to beat them at their own game. Williams made a point of not going what he called “the Disney route.” But by 1993, all other routes had been blocked off.

With only fifteen minutes of footage still incomplete, Warner Brothers sold off the project to the highest bidder. One potential buyer, Sue Shakespeare, offered to complete it with both Richard Williams and no less a talent than Terry Gilliam (because when has any film he was involved with been left unfinished?). The ominously named Completion Bond Company also put in an offer, sans Williams. Guess who got the project?

The Completion Bond Company snatched what was left out of Richard Williams’ hands and patched together the scenes that hadn’t already taken William’s loving touch with sub-TV quality animation. As a final insult, the silent heroes were dubbed over with incessant chattering by Matthew Broderick and Jonathan Winters, and Disney-style songs (as in, someone who apparently saw a Disney movie once and took a songwriting class never threw it together) were added into the mix. WIlliam’s masterpiece, his favored child got dumped in just over five-hundred theaters, and still too late to be recognized as anything but an Aladdin cash-in.

Because of all this, underlying the joyful, almost exhausting exuberance of The Thief and the Cobbler’s spectacle is a heavy sense of loss. It’s hard to imagine how different the medium might have been if the movie had gotten the mass audience Williams dreamed of. He had already kickstarted one animation renaissance with Roger Rabbit – could he have inspired another one five years later? His low-tech 3D effects proved CGI redundant – would the technology have developed the same way if it had this to compete with? Would it have overtaken the hand-drawn method, or would Williams’ studio still be cranking out lovingly detailed masterpieces in ink and paint today? Or was his vision, like Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune too ambitious and strange to ever come into being? We can never have answers to these questions. But at least we still have The Thief and the Cobbler.

Richard Williams said that when he was a child, he had wanted to be an animator. Then, as he grew up and discovered fine art, he wanted to be Rembrandt. And then, he saw Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and realized he could be both. However unrewarded his genius may have been, he still lived up to at least that one dream.

If you’d like to learn more about Richard Williams – and why the heck wouldn’t you? – check out YouTube’s The Thief Archive for a fantastic overview of his work, including the “recobbled” cut of The Thief and the Cobbler that was the basis for this review.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCzhbXXKqKUNEI2TOFI1MI5g