If I may repeat myself from the last time we discussed Peanuts: once upon a time, my mom caught me pulling out our old VHS of Snoopy Come Home.

“This always used to make you so happy!” she said.

“But why?” I responded, “It’s so sad!”

But like all of creator Charles “Sparky” Schulz and director Bill Melendez’ work, that’s kind of the whole deal. There’s a lot of sadness in Charlie Brown and Snoopy’s world, but there’s also a lot of joy; and the most of the sadness there is the cathartic kind, with a heartbreaking beauty that goes far beyond its cartoon simplicity and even its occasional outright shoddiness. The long history I’ve mentioned with the movie makes me doubt my continuing love for it. Could this cheapie little cartoon really be as powerful as it seems to me? Isn’t it just the stimulus and response of nostalgia? But if Snoopy Comes Home continues to move me even after multiple viewings as an adult, there must be something to it. To paraphrase Schulz and Melendez’ first collaboration, it’s really not such a bad little cheapie cartoon.

(Funnily enough, as you might have guessed from my conversation with my mom, I don’t remember it affecting me in nearly the same way as an impressionable kid. Maybe it was over my head. But then, I also started bawling when I watched Snow White die for the fiftieth time and already knew she’d be fine, and I was too scared to watch The Hunchback of Notre Dame for years, not because of any of its truly disturbing moments, but because of a goofy slapstick gag where a little old man falls down a manhole — so who even knows what was going on in that little bitty brain of mine.)

Like Melendez’ previous feature-length adaptation, A Boy Named Charlie Brown, Snoopy Come Home doesn’t so much have a plot interrupted by comic or artsy interludes as it’s a series of interludes that are occasionally interrupted by the plot. It’s a remnant of a time when kid flicks could fill out their runtime with whatever little side alleys the creators felt like going down, for good and for bad. Since Disney’s nineties resurgence and Dreamworks’ establishment of an equally hidebound alternate model, these types of movies have been the victim of relentless studio notes to “tighten up” their screenplays and cram them chock-full of formula boxes to check off. Snoopy takes over twenty minutes before the plot even introduces itself: Snoopy receives a letter from someone named “Lila” and dashes off with Woodstock to visit her in the hospital. (I told you this was sad — don’t worry, she’s released before the movie’s over.)

This is all based on a story that Sparky got through in a week or two’s worth of four-panel strips. He and Melendez come up with ways to expand the plot — Snoopy’s adventures on the way to Lila or his decision of what owner to stay with — but they’re at least as interested in bringing it up to feature length with a series of vaguely connected vignettes. Most of them are simple gag setpieces, either based on Sparky’s Peanuts strips or taking advantage of the medium shift for elaborate cartoon slapstick that would have been impossible on the static newspaper page. But others are unexpectedly lyrical and impressionistic. Melendez had taken this approach for A Boy Named Charlie Brown in the psychedelic sixties, and while nothing here is as unassumingly avant garde as Schroeder’s Beethoven recital or the multi-screen baseball game, it still makes the case that Melendez wasn’t just a hired gun for the Peanuts mini-media empire, but a great filmmaker in his own right.

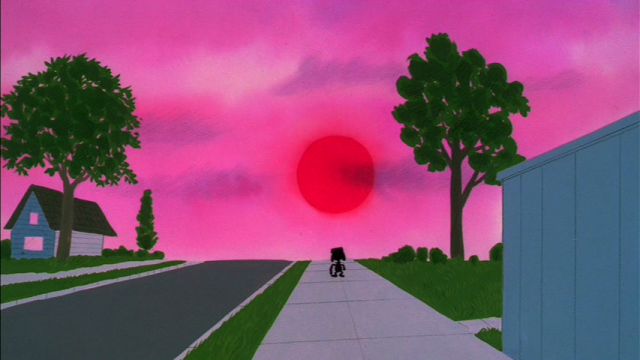

There’s long, atmospheric pans over landscapes that resemble Schulz’s artwork less than the era’s children’s books or even fine-art watercolor studies, filmed with what appears to be a downmarket version of the “multiplane” camera Disney developed for The Old Mill and Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Some scenes just take a moment to observe the beauty of nature without regard to the plot or characters, like an animated version of Tarkovsky or Terrence Malick: the brilliant red of the sunset, or the grace of a flock of geese passing in front of the full moon. Charlie Brown’s psychedelic effects return for the wonderfully bold, nearly abstract opening credits and for a dream sequence where Snoopy and Woodstock wander transparently over a series of equally abstract watercolor landscapes. Necessity might have been the mother invention here: not only do these scenes fill time, they presumably save money (that was certainly the case for Charlie Brown’s flying ace dream sequence, which, strikingly designed as it is, also allowed the crew to reuse animation from It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown). But whether or not Melendez set out to make fine art, that’s what he did. If nothing else, as kids’ media gets noisier and more frantic seemingly every generation, it’s refreshing to see something that encourages them to be quiet for a moment. Could my adult love of slow, arty films be down to my early exposure to this movie? I’m not ruling it out, that’s all I’m saying.

A major reason for Snoopy Come Home’s patient quietness is also a matter of necessity: its primary character doesn’t talk. This makes him a very different character from the verbose Snoopy of the comics; in some ways, it flattens him into less of a misanthropic intellectual and more of a cute cartoon animal. But not completely; Snoopy Come Home’s expressive animation brings a lot of his personality to the screen, and one of the movie’s major themes is what it means for Charlie Brown and his friends to love someone who’s often pretty unlovable. He’s not completely voiceless either: Melendez himself provides unique and memorable animal noises for him and, starting with this film (the credits proudly declare “Introducing Woodstock” like he was a major movie star) Woodstock too. Melendez and Schulz even manage to make their star’s voicelessness a plot point and a setup for some of the movie’s most memorable gags. When Snoopy gets Lila’s letter, he runs off without telling Charlie Brown where he’s going or who wrote it, leaving his poor owner with no idea what’s going on. (“If I don’t find out who Lila is I’ll go crazy!”) Of course Snoopy doesn’t explain — how could he? When he returns, Charlie Brown peppers him with questions and, in a moment of self-awareness, looks out to the audience to tell us, “I’m not getting any answers.”

This is just one of Melendez’ eccentric casting choices. Another, more obvious one, is the decision to have the human characters played by real children. Nearly all animated children are voiced by adults (as Bart Simpson wrote on the chalkboard for his voice actor’s birthday, “I am not a 32 year old woman, I am not a 32 year old woman, I am not…”) Peanuts is the last series you’d expect to break with that tradition. After all, half of the comedy comes from just how un-childlike these children are. But even though it required frequent recasting (Snoopy Come Home has an almost completely different cast from A Charlie Brown Christmas and It’s the Great Pumpkin), it was the right decision. Melendez wouldn’t have as good of luck in the future (I’m still a little haunted by a later special I saw as a kid where Lucy throws Schroeder’s piano down a storm drain and jokes that if he tried to play it now he’d hit a “sewer note” — but Lucy’s voice didn’t understand the pun and butchered it by emphasizing the wrong word!). But this second generation of Peanuts Players do beautifully with Sparky’s dialogue, selling the incongruity of lines like “I’m going to destroy you economically, Charlie Brown” or “A beep on the nose is a sign of great affection” coming from the proverbial mouths of babes. Though they’d each make a brief career out of playing these characters, they still keep that nonprofessional edge that makes them seem more like real kids than sitcom cuties, no matter how far their vocabulary gets above their grade level. Sometimes, though, that works against them — I have to feel sorry for the poor kid who played Charlie Brown when he gets a solo musical number well out of his range. But even there, the straining voice fits poor Charlie Brown, straining with emotions he can barely process.

That amateur ethos is essential to what makes the Peanuts films and specials work. Most low-budget animation, like the assembly-line entertainment Hanna-Barbera was cranking out at the same time and that’s only gotten uglier with modern technological shortcuts, looks like it was made without heart or care. There’s not a huge difference between that and what Melendez is doing here at a technical level. But the unpolished performances and artwork — Snoopy Come Home is a very tactile movie, with its watercolor splotches and pen-nib scratches — create a feeling, based in reality or not, that we’re looking at a scrappy labor of love and not the half-hearted work of budget-conscious drones. It probably doesn’t hurt that Melendez had some serious talent on board despite his limited means. The credits for “Graphic Blandishment” include Rod Scribner, who’d animated some of Looney Tunes’ looniest moments for director Bob Clampett, and Phil Roman, who’d later go on to found Film Roman, the studio behind The Simpsons and King of the Hill.

Ironically, one of Snoopy Come Home’s weakest aspects came from its big-name professional songwriters, the Sherman Brothers. They had decades of success and experience creating the iconic soundtracks for Disney movies like Mary Poppins and The Jungle Book. Some of their work here lives up to that standard, especially our introduction to Lila with Shelby Flint’s haunting soprano performance of “Do You Remember Me?” But others suggest they were phoning it in, or, with the unfortunately omnipresent “The Best of Buddies,” seeing how much instantly-dated seventies lingo they could cram into one song, with lyrics like:

We’ve got good vibes,

Our friendship jives…

Harmony is where it’s at,

And where it’s at for you is where it’s at for me…

Now we’re groovin’,

Gettin’ it together,

Makin’ it all come right,

Really movin’,

Gettin’ it together.

The feelin’ is

Out of sight…

A-OK now,

Ramblin’ and a -rappin’

Shakin’ the status quo!

Much better is “No Dogs Allowed,” more of a running gag than an actual song, which has had a long life in my family. And no wonder: that refrain is bellowed by Thurl Ravenscroft, who had previously engraved “You’re a Mean One, Mr. Grinch!” and “They’rrrrrrrre great!” on all our consciousnesses. Even better is the instrumental score by Don Ralke, which turns on a dime between goofy and moody, and which brings out the atmosphere of Melendez’ silent interludes.

So, why is this movie so sad I couldn’t believe it used to make me happy? Well, when Lila recovers, she asks Snoopy if she can re-adopt him. With the impossible choice between her and Charlie Brown and all his other friends, Snoopy goes home to say goodbye. This leads to the movie’s peak, a farewell party where the whole cast cries their eyes out. It’s so over-the-top that it’s both hilarious and heartbreaking — there haven’t been this many tears on screen since Alice literally cried a river in Alice in Wonderland. It’s all the more effective because the kids are played by real kids — when you’re listening to a whole roomful of little children bawling all at once, just try to ignore the primal mother instinct telling you to join in. Melendez even manages to make his sped-up cartoon voice for Snoopy chillingly effective when he starts howling and sets everyone else off.

After Snoopy leaves, Charlie Brown deals with his grief in much smaller, but no less moving ways. He’s gotten his grand shows of emotions out of the way, and now he expresses his loss more subtly: lying awake in bed, making himself a bowl of cereal that he’s unable to eat, walking to Snoopy’s doghouse in the dark, and resting his head against it. The Shermans expand his comic-strip one-liner, “Goodbyes make my throat hurt. I need more hellos” into a haunting little mourning song.

Like I said, it’s an impossible situation. How can Snoopy decide between his ramshackle little neighborhood family and a sickly little girl who loves him just as much? The solution doesn’t quite land, even if it does pay off the “No Dogs Allowed” runner when Snoopy discovers it written on a plaque outside Lila’s apartment building. It’s a little too easy a solution to a dilemma the movie had dealt with up until then with surprising depth and maturity. And Snoopy’s a little too happy to abandon Lila — he doesn’t even try to hide it from her!

And when Snoopy, as the title promised, comes home, the movie ends on an oddly sour note. He demands Charlie Brown’s friends give him back everything he left to them when he thought he wouldn’t be coming back. They all storm off as Lucy yells, “That does it, Charlie Brown! He’s your dog and you’re welcome to him!” Charlie Brown’s left alone with Snoopy, and as Snoopy dramatically conducts the end-credits music, Charlie Brown rolls his eyes, shrugs, and leaves too. The scene touches on that theme I mentioned earlier about loving someone unlovable. But in the process, all the relationships we’d gotten so improbably invested in for a silly little cartoon are damaged. Snoopy’s left alone, and suddenly it’s just a silly little cartoon again. It’s a weirdly flat ending for a series that has been so graceful dealing with complex and conflicting emotions, on screen and in print. It leaves viewers with an oddly cynical image of the relationship that the past hour and a half had handled with so much tenderness. And after exploring the serious issues of friendship and loss with so much depth of thought and feeling, Snoopy Comes Home suddenly abandons them for a quick fix to restore the status quo (I thought we were shakin’ that up?) in time for the next special.

Oh well. At least we have time for one more moment of beautifully calibrated catharsis on our way to that literal shrug of an ending. It even justifies the existence of the “Best of Buddies” song. Woodstock silently pecks for food on the sidewalk, another scene that modern animators would demand be actioned up. The song starts playing softly, and Woodstock puts his ear (do birds have ears? anyway…) to the ground. He hears Snoopy walking back, and the music swells as Woodstock whistles along. Soon all the kids see Snoopy’s back and they join the song, carrying him home on their shoulders like a football champ. It’s a scene that calls back to the iconic chorus of “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing” in A Charlie Brown Christmas, and if it doesn’t have quite the same power, it’s darned close. Scenes like these display what Peanuts can be at its best: a comic to make you chuckle politely over your morning coffee, sure, but also one that’s capable of moments of heart-stopping beauty. If Snoopy Come Home can’t live up to that standard all the time, the moments that do make it more than worthwhile.

Want to keep Sam up to his best? Then donate to his Patreon!