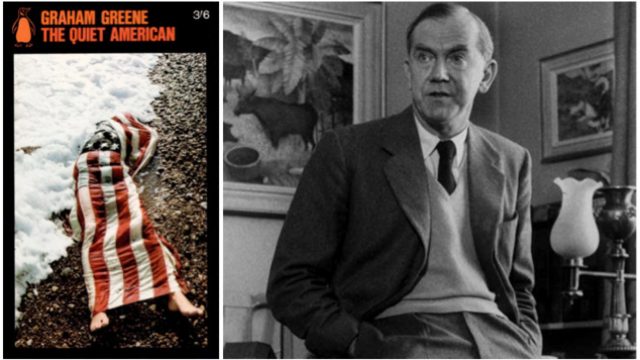

The political noir genre and unreliable narrator go together like love and war. But in The Quiet American, written by Graham Greene, the narrator, Fowler, a British journalist in Vietnam, isn’t exactly lying to us when he tells us what he’s done. Due in part to bad timing (a letter that arrives too late), he’s profoundly compromised himself, trashing his ideals for what he believes is a last chance at happiness.

Of course, someone needed to stop Pyle, the rogue operative—the quiet American himself—from killing innocent civilians in his misguided conspiratorial quest to remake Vietnam into a quasi-American democracy. Greene, however, suggests that Fowler sets him up to prevent him from taking Phuong, his lover, away from him. There’s the rub: can an act be heroic if committed because of a cowardly motive?

Now, I’m speeding up the narrative, which moves with a graceful pace, to point out that we most probably like Fowler and don’t much care for Pyle, at least as Fowler characterizes him: “He belonged to the skyscraper and the express elevator, the ice cream and the dry martinis, milk at lunch, and chicken sandwiches on the Merchants Limited.”

After this earlier take down, it’s tempting to keep laughing at Pyle, even as he goes to his end, which we may well say he rightly deserved. Yet such an attitude brings us closer to the conclusion that the end justifies the means, the same belief that Pyle held. The more we find the novel entertaining, the more we overlook its ethical implications. Greene makes sure we can’t have it both ways.

But not only is the novel entertaining; it does have a moral certainty about the brutality of war. A French officer with the colonizing forces describes the aerial view of a napalm bombing: “You see the forest catching fire. God knows what you would see from the ground. The poor devils are burned alive, the flames go over them like water.”

Before American troops were on the ground, which blew up this corruption into a “bright shining lie,” the novel focuses on a series of small, questionable acts. There’s something downright creepy about Fowler’s view of Phuong: while the logic he uses to justify their relationship may not be as confining as Pyle’s stale romantic fantasy, the pride he takes in granting her a certain measure of freedom does not lend itself to a very charitable interpretation.

Fowler may not have the money Pyle has (who, at times, becomes a symbol for American economic imperialism). Greene would remind us, however, that money is not the only corrupting influence. Fowler will find other means to do his dirty work, all done with the cool detachment of his favorite nightly ritual, getting ripped by smoking opium.

The French officer, quoted earlier, says to Fowler, “We are fighting all of your wars, but you leave us the guilt.” Fowler’s thinking, throughout the novel, that he’s not taking a side, is a delusion, a chemically-enhanced image of himself as a man of reason.

Although Fowler’s penchant for understatement is not as grating as Pyle’s doublespeak (a chilly Orwellian breeze blows through Greene’s evocation of Vietnam), Fowler’s embrace of Vietnamese culture has more than a hint of a colonialist tunnel vision. That he’s there because of a prolonged self-exile from England doesn’t do him any favors when he makes it a habit to refrain from taking the higher moral ground in his arguments with Pyle.

After we’ve unpacked how Pyle’s saving Fowler’s life is a riff on Pyle’s missionary zeal (saving someone who couldn’t really care less if he were saved) and then added up the carnage Pyle has caused, our attention is pulled back to Fowler. While he may not be an unreliable narrator, there are critical moments when he commits the sin of omission. These moments pile up at the end to suggest the pain of holding back and turning away from the future. Granted, there’s a grim logic here: things won’t get better for the Vietnamese; they’ll only get worse. American troops will see to that.

The Quiet American is a fine example of how taut writing can get to the traumatic core of warfare. Robert Stone’s pulse-pounding Dog Soldiers (1974) seems influenced by Greene’s razor-edged depictions of moral dis-ease. Stone transforms the recreational opium use in The Quiet American into a shipment of uncut heroin smuggled from Vietnam to America. Chaos reigns: Pyle’s country has degenerated into lawless, wanton brutality. The cops are dirty; the American journalist in Vietnam who arranges the drug deal appears even more feckless than Pyle.

Published in 1955, The Quiet American (drawing on Greene’s experiences as a Vietnam journalist) chronicles a time well before the war came home to America. But the seeds are planted for the catastrophe of Dog Soldiers. The belief that a person or a country can do no wrong twists and deforms the legal criteria for determining why America was in Vietnam in the first place.

Reading Greene’s novel also, I think, may give a better appraisal of the argument that Steven Spielberg sort of lost the thread in The Post (2017). The publishing of the Pentagon Papers, which disclosed the extent of American involvement in Vietnam never made public, happened after much of the damage was done. It may have helped resist the authoritarian impulses of the Nixon administration; the responsibility, however, for what was done could only be assumed after the fact.

We’re well aware that Fowler doesn’t go for easy sentiment, which further toughens the sentence passed on Pyle. Greene lets us see the making—and unmaking—of Pyle, casting light on the creation of fantasies about Vietnam, already in progress, that would lead to an all-out American military campaign.