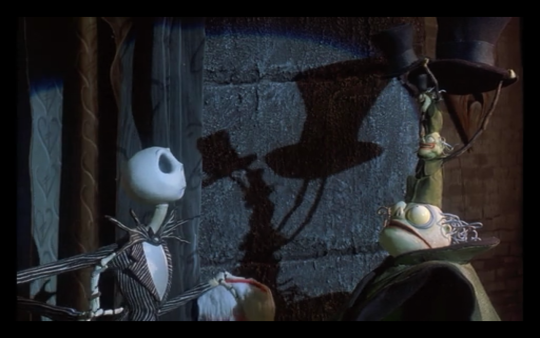

In the twenty-four years since its release, The Nightmare Before Christmas has gone from weird little sleeper hit to cult oddity to cult classic to an annual tradition for hundreds of moviegoers (and, since it covers both Halloween and Christmas, could even be watched twice a year). In a lot of ways, it’s the perfect movie to fill that role, because no matter how many years in a row you watch it, every frame is so packed with detail that there will always be something new. My viewings must be into the double digits by now, but rewatching it for this piece, I still found things I never noticed before, like the little rats in party hats scurrying around the “Making Christmas” sequence or the wonderfully creepy little touch of the demonic trick-or-treaters Lock, Shock, and Barrel kneeling before the entrance to Oogie Boogie’s lair like worshippers before an altar. Even though it was all built at something like 1/10th life size, Halloweentown feels more real than the Cinematic Universes of nine out of ten Hollywood spectaculars. A world populated entirely by spooky carnival horrors is hardly an original idea on its own; even by 1993, it was almost cliché. But producer/creator Burton and director Henry Selick (and you have to talk about them together – Nightmare almost seems like it was directed by a composite filmmaker along the lines of the “Spielbrick” Wallflower imagined creating A.I.) aren’t content to just take the familiar horror icons off the rack. There’s werewolves and vampires here, but where else are you going to find a giant, shambling burlap sack full of creepy-crawlies with a snake for a tongue, or a version of Dr. Caligari with miniature versions of himself stacked on his head like the Cat in the Hat?

We’ve seen all kinds of permutations of Frankenstein and his monster, but this is still the only time the monster was a literal ragdoll stuffed with leaves who can pull out the stitches and sew them back together so her hands can fly around on their own, or a doctor who can flip his head open to scratch on his brain.

It’s hard to remember just how unique this all is after Disney has stuck Jack Skellington’s grinning skull on every product known to man. It’s especially odd given the movie’s history — the studio originally distanced itself from the film since it got a scandalous PG rating (gasp!) and released it under the Touchstone banner.* It wasn’t until about a decade later that they realized that its viewership had grown into an enormous fandom they could cater to. And why shouldn’t it? Nightmare was to the millennial “monster kids” what reruns of the Universal classics were to Burton and Selick’s generation. And as that generation’s introduction to the Burton aesthetic they would copy in their clothes, art, and makeup, this might be one of the defining films of our generation — certainly up there with any one of Disney’s in-house productions. But there’s a paradox here — what drew so many weird, out-of-place kids to the movie was just how weird and out-of-place the movie itself is. Can that appeal coexist with the film’s transformation from hour-and-fifteen-minute passion project to global phenomenon? Disneyland has at least one whole store devoted to Nightmare merch; when the company launched its Disney Infinity role-playing game in 2013, they sold Jack in the second wave of characters, ahead of company cash cows like Winnie-the-Pooh, Lilo and Stitch, and all but the newest princesses.

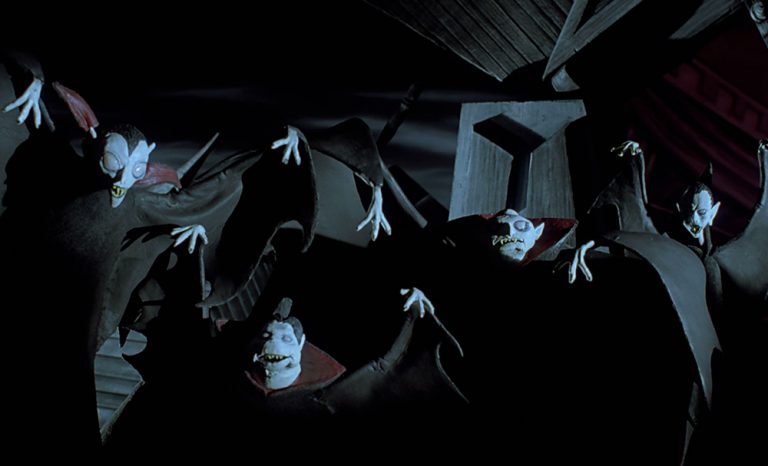

I shouldn’t be shocked that a children’s film produced by a filmmaker coming off one of the biggest movies of all time in between work on its sequel and distributed by the towering giant of kiddie entertainment would keep its hand in the marketplace for so long. I shouldn’t be offended either — it’s hard to imagine Burton and Selick went into this project hoping not to make money, after all. But watching the film itself apart from its place in the zeitgeist, it’s hard not to be struck by just how uncommercial the whole thing is. Most Disney products look sleek and expensive: this one has the kind of grungy DIY look that the studio would normally polish all the edges off of. Selick has little to no interest in hiding the seams in his miniature stars when they’re blown up across the screen. They’re remarkably tactile, and not just with the gritty, fingerprint-covered texture of other stop motion films. Their eyes are almost slimy, their skin mottled and craggy. The mad scientist Dr. Finkelstein is already grotesque enough, but he’s often placed right next to the camera so we can fully take in every one of the wrinkles where one layer of clay mashes up against another. Several of the lovingly-designed background characters have been immortalized in plastic, but can you imagine grotesquely-detailed oddly-proportioned figures like the vampires and the rotting corpse family on a toy store rack?

Jack’s minimalist, almost smiley-face design fits well on a coffee mug, but you notice how they always have his mouth closed you can’t see his crooked yellow teeth?

At a time when computer technology was making stop-motion so smooth it was almost indistinguishable from live action, Selick couldn’t care less about whether his characters dive into the Uncanny Valley, with their too-big eyes and too-small teeth. Even our hero, who seems more or less like us most of the time, can suddenly become totally alien, scuttling up walls like a spider and flipping like pressurized water in the climactic battle.

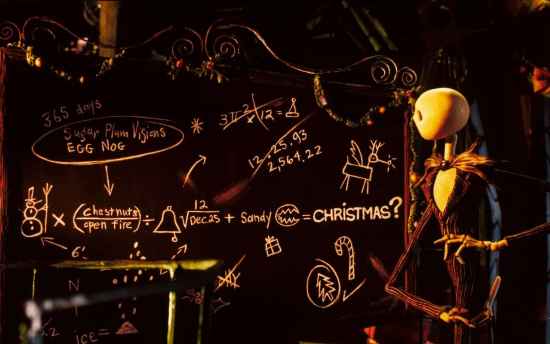

The Disneyfication of Nightmare is even more fascinating because of how much it’s reflected in the plot of the film itself. Jack becomes so possessive of Christmas that he misses what makes it Christmas and tries to recreate it as something more familiar to him. That sequence of him trying to crack the mystery with the help of his big black book labeled “The Scientific Method” is a mini-masterpiece in its own right, by the way, getting at the maddening refusal of some things to be rationalized that has driven so much of Burton’s work, to say nothing of hundreds of other great artists. Is there any more elegantly, hilariously simple distillation of the theme Wallflower calls “reason as madness” than this?

And there’s that beautifully subtle-for-a-kiddie-movie foreshadowing with all the ways Jack destroys his souvenirs of Christmastown when he tries to study them, melting the candy cane, crushing both the holly berry and his microscope slide, and shattering ornaments left and right as he dance with the tree and crows about how he’s finally figured it out. Anyway, the way he words it should be enough to bring us back on task:

And there’s that beautifully subtle-for-a-kiddie-movie foreshadowing with all the ways Jack destroys his souvenirs of Christmastown when he tries to study them, melting the candy cane, crushing both the holly berry and his microscope slide, and shattering ornaments left and right as he dance with the tree and crows about how he’s finally figured it out. Anyway, the way he words it should be enough to bring us back on task:

I think I can improve it too!

And that’s exactly what I’ll do!

That’s where Jack meets the holders of his trademark. Christmas is so wonderful, but wouldn’t it be better if the reindeer were skeletons? And The Nightmare Before Christmas is so wonderful, but I think I can improve it too, and that’s exactly what we’ll do. Jack’s blank face makes it so easy and simultaneously disturbing to identify with him, but wouldn’t it be better if he had just a little Dreamworks smirk?

And Sally’s such an inspiration to the misfits of the world, but what if we made her just a hair more conventionally attractive? And those weird, wiry eyelashes have to go, let’s space them out more and make them all pretty and delicate. And those bugged-out eyes, we can’t have that – “try something fresher, something pleasant!”

And Sally’s such an inspiration to the misfits of the world, but what if we made her just a hair more conventionally attractive? And those weird, wiry eyelashes have to go, let’s space them out more and make them all pretty and delicate. And those bugged-out eyes, we can’t have that – “try something fresher, something pleasant!”

And like Jack, despite their enormous success, the marketing people seem to miss what drew them to their subject in the first place, its weird, knobby, uncomfortable oddness. But even that’s fitting in a way. What could be a better tribute to an artist as enamored of classic kitsch as Burton than for his style to become a kitsch item itself?

I am, of course, overstating just how weird this film is — it was a Disney production from the beginning. And anyone familiar with some of Burton’s colleagues in the cinema du weird like David Lynch (the Tim Burton of the art house) can, and often do (very loudly) find him more than a little too safe. Once we graduate to those films, this one no longer seems so weird, and once we graduate to the great horror filmmakers, it doesn’t seem so dark or frightening. But in a way, the safeness of Burton’s films, this one in particular, is actually part of what makes their transgressive thrill so powerful. For one, he makes his monsters heroes rather than threats, far more explicitly than he could in a film where they have to scare the audience. Norman Bates and Frankenstein might tug at our heartstrings, but they’re still the horrific Other. When the monstrous becomes normal, does that mean what’s normal is monstrous? (That’s certainly the case in other Burton films like Edward Scissorhands). And if we identify with these monsters, that makes us confront why we identify with them, and it’s good for a guilty shiver when we realize they may be as ugly inwardly as they are outwardly – how many other movies are going to make you sympathize with a character who terrorizes children and kidnaps a figure of pure goodness like Santa Claus? It’s an effect Burton’s teacher Vincent Price perfected, and the younger filmmaker is, if anything, even more masterful with it. And just when we get too comfortable with this weird, shadowy world, the glimpses of real horror become even more shocking. Oh, Jack’s just like me…oh, did he just pull out his own rib and throw it to his dog? And that’s to say nothing of one of the most traumatic and oddly moving death scenes in the family genre, when Jack tears Oogie Boogie open and all the insect colony he was made of squirmily disintegrates as he repeats, his voice becoming steadily more inhuman, my bugs my bugs my bugs my bugs…

You can’t talk about the film’s mix of coziness and creepiness without giving due credit to composer/vocalist Danny Elfman. His music has the same tonal wrongness as the old Brecht-Weil musicals, but in his hands it’s something totally unique; his scores to this and his other Burton collaborations are immediately recognizable and unmistakable. The song score to Nightmare has a wild, careening, out-of-control sound that’s both fun and frightening — a merry-go-round broken down. I remember as a child feeling viscerally guilty to have “Kidnap the Sandy Claws” stuck in my head in church. And the score’s subtle moments are equally powerful: in a genre that, now than more than ever, feels the need to come right out of the gate with screaming bombast to hold the little brats’ attention, the quiet, melancholy notes that open Nightmare almost literally cast a spell. Almost a quarter-century later, it still haunts us.

* Burton’s fraught relationship with Disney goes beyond that: he began his career as an animator for them, and found work on The Fox and the Hound so mind-numbing that he started doodling the heroes as roadkill. Not knowing what to do with him, Disney had him doodle all day as a “concept designer” for The Black Cauldron. He later provided them with a wonderfully creepy version of “Hansel and Gretel” as a Halloween special for Disney Channel — and then pulled it for being too scary for the target audience.