Imagine a split-screen image with rural Northeast Ohio on one side and Birmingham, UK on the other: you couldn’t help but notice similarities in their relatively blank, monochromatic landscapes, if you’d notice either of these places at all. Having the dubious honor of known for being perennially under the cultural radar, both places elicit feelings of austerity that could serve as powerful artistic fuel.

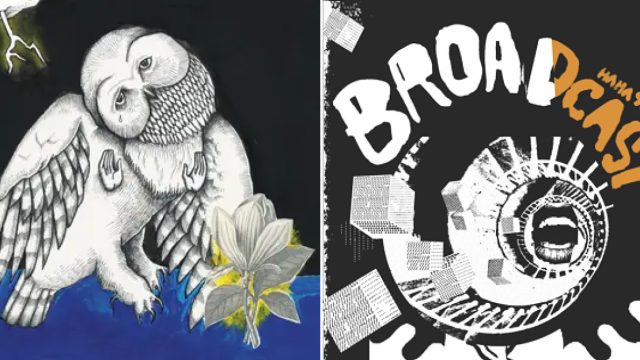

Songs: Ohia, the name of Jason Molina’s solo project, of course, traces his Midwestern roots, while Broadcast was formed in Birmingham by vocalist Trish Keenan and bassist James Cargill. In 2003, Molina released The Magnolia Electric Co. and Broadcast put out HaHa Sound. Both records fill in the spaces of what seem to be experiences partially recalled, partially dreamed, mythical as well as cosmic. Magnolia opens with the moan of a slide guitar sounding like the mill closing down for the weekend, or maybe forever. Then a sonic gale erupts during Molina’s first line: “The whole place is dark,” with every instrument, in the dense mix, dialed in perfectly. HaHa Sound starts with fluttering keyboards and Keenan singing: “I am grey, still on the page/Oh colour me in,” her voice floating over an increasing racket of electronic effects.

Play the two records back-to-back, and they ebb and flow uncannily in concert with one another. Magnolia mines the music of Bob Dylan and Neil Young. HaHa Sound continues Keenan and Cargill’s infatuation, featured on their 2000 debut album The Noise Made By People, with the underground psychedelia of The United States of America, whose 1968 self-titled record Broadcast took as a founding document (for Keenan’s spaced-out vocals, especially). As Keenan joked in a 2003 interview, “That’s it, we’ll rip that off for the next 10 years.”

In a rather morbid connection, both Molina and Keenan evoke that unexplored country they’d arrive at too soon: Molina died 10 years later from alcoholism at the age of 39; Keenan 8 years later from pneumonia at the age of 42. You can’t help but feel moved right down to your very soul when Molina sings, “Almost no one makes it out/ You’re talking to one right now/ For once, almost was good enough.” While, at the end of HaHa Sound, Keenan turns these feelings of loss back on us: “Speak your words, define my grief for me/Out of reach, some things just cannot be.”

I trust, of course, that no one thinks I’m calling Magnolia and HaHa Sound advance obits for Molina and Keenan; after all, that long goodbye is a recurring theme in country and psychedelic music, which spang up from wherever folk music had been or was going. Even when Molina lays his cards on the table, he’s got a joker up his sleeve: “And everything you hated me for/ Honey, there was so much more.” Molina’s doubling down on despair has a tragic humor that fits with the pantheon of country-folk troubadours from Hank Williams Sr. to Townes Van Zandt.

As for Keenan, she’d be the first to tell you creepy death images go hand in hand with stories of a woman’s sexual awakening: she’s an obsessive fan of Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970), a completely bonkers Czech film that uses the vampire trope to play in the garden of earthly delights. “Valerie,” from HaHa Sound, pays homage by riffing on the film’s theme music, making it noisier, more electronic – owning it. One of the keys to unlocking Keenan and Cargill’s repurposing of the past, “Valerie” grimes up the retro-futurism of the space-age swinging bachelor-pad set.

What, however, separates the two records is how they were made. Magnolia was cranked out in just three days. The band that Molina assembled for the album had only a brief chance to hear the songs before tracking them at the Chicago studio of Steve Albini, the guy you’d absolutely need to handle the technical demands of such a time-sensitive project. In contrast, HaHa Sound took nearly three years, as Keenan and Cargill’s artistic process involved using a church hall as a makeshift echo chamber to add ambience to the songs crafted at their home studio.

Regardless of the production differences, the casual listener is likely not to recognize them on either record without the backstory. At the start of the bridge of “Just Be Simple,” Molina and his band slide into a liquid chord change that could’ve been from Neil Young’s Tonight’s the Night (1975), on which Young and his band got wasted to mourn the deaths of their close friends, stumbling their way towards making an essential text of the downer-rock canon. Yet Magnolia, on the whole, has an unnerving precision, as if Molina conjures a guiding force, or, as he puts it, “I’ve been riding with the ghost.” An unearthly presence also registers on HaHa Sound: the standout single, “Pendulum,” has the first-take intensity of 60s garage rock welded onto Keenan’s experience of astral projection (which, she says, happened to her in real life): “I’m in orbit, held by magnets/And the force feels so much closer than love.”

And for Molina and Broadcast, these records are career milestones. Molina’s artistic accomplishment so inspired him that he changed the name of his band to Magnolia Electric Co. HaHa Sound sits in the middle of an impressive three-album run. The subtle focus shifts of The Noise Made By People set a high standard, but HaHa Sound further enriched and expanded the tonal color palette. Then two years later, Tender Buttons (2005) went the opposite way, subtracting ruthlessly to amplify an avant-garde, (post-)modernist buzz, turning Gertrude Stein, from whose 1914 book of poetry the album title was taken, into a fellow astral traveler.

Of course, the 20-year anniversaries of Magnolia and HaHa Sound have now been duly celebrated (here and here). If that’s what it takes to get people to listen to them, so be it. But these records also have a timeless quality, reflected in their koan-like messages: “For once, almost was good enough” and “so much closer than love” shake us out of our expectations and invite us to consider what’s yet, even, to be dreamed. Here’s hoping people pick up on that too.