While the “Golden Age” is mostly used now by DC and Marvel to milk nostalgia for men in capes punchin’ Nazis, what really made it golden was the variety. There was something for everyone, from Fairy Tale Parade for pre-literate storytime to Young Romance for adult or aspiring-adult women. And that made comic books more popular than they’ve ever been since. Even now that characters who originated there are dominating other media, comics can’t hope to match the days when 41% of men and 28% of women read six comics every month, based on a 1944 survey that doesn’t even get into how enormous funnybooks were with their core kid audience.

Every publisher tried to cover as much of that market as they could, but EC Comics covered it all, and they did it better than anyone else. Science fiction in Weird Science, romance in Modern Love, humor in Mad and Panic, crime in Shock and Crime Suspenstories, and war in Frontline Combat, not to mention all but inventing the horror comic with the wildly successful Tales from the Crypt and its spinoffs. They even dabbled in superheroes with Moon Girl before it was retooled as A Moon…A Girl…Romance! and finally Weird Fantasy.

Unfortunately, they got too successful for their own good, and the big dogs moved in to protect their territory. Exploiting the moral panic over crime and horror comics, the major publishers, led by DC and Dell, created the Comics Code Authority in 1954, allegedly to protect the fragile little minds of America’s children, but actually to run EC and other upstarts out of business.

And it worked. By 1956, EC was down to a fraction of its former output, with that number declining every month. By summer, Mad was the only book they had left. By fall, DC’s Showcase introduced a new version of the Flash, a blockbuster hit that solidified DC’s dominance and opened the door for Green Lantern, Supergirl, the Justice League, and all the rest — and, eventually, the Marvel Age of Comics. The Golden Age was offically dead. Long live the Silver Age.

Mad turned out to be the key to EC surviving as long as they did. The book’s creator, Harvey Kurtzman, pushed his boss William Gaines to upgrade it from a flimsy comic book to a slick black-and-white magazine (we’ll get to that). Soon, Mad was bigger than ever, and Gaines began transitioning his other books to the same format.

That’s how we got Picto-Fiction, a middle ground between comics and the combination of text and “spot illustration” that was popular in contemporary fiction magazines. After all, the Comics Code Authority couldn’t touch books that technically weren’t comics, right? The Tales from the Crypt equivalent is even named Adult Tales of Terror Illustrated, just to make sure nobody got the wrong idea.

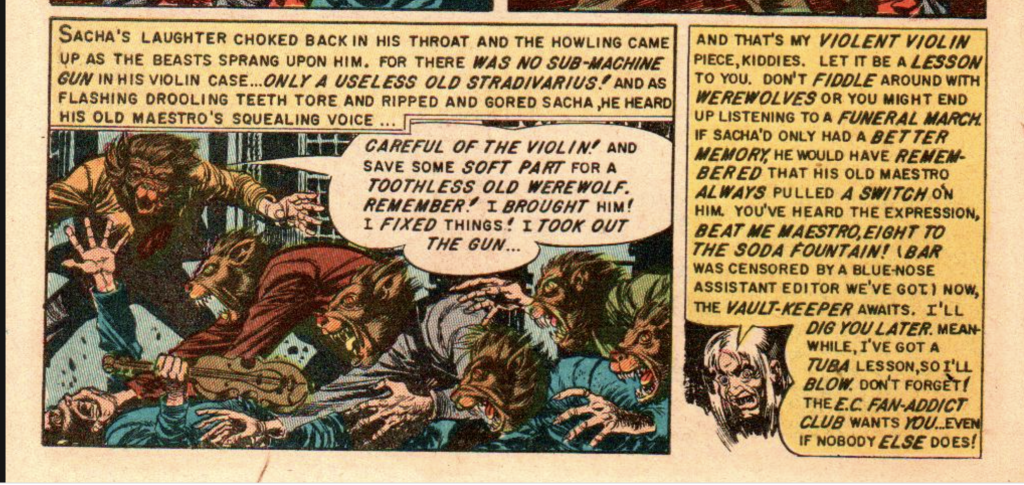

Picto-Fiction was more than just a utilitarian move. It was the direction EC had been headed all along. Al Feldstein’s stories were already too wordy to fit into the conventional comics format. How many Tales from the Crypt stories wrapped up by squeezing out the art to make room for the florid descriptions of the twist ending and the sizes of the Crypt Keeper’s pun-soaked epilogues reducing him to a tiny floating head?

It’d be easy to assume Picto-Fiction would privilege the stories above the art. But the reality was just the opposite. EC’s greatest strength was always its stable of artists, who read like a list of the greatest of the era: Kurtzman, Wally Wood, Jack Davis, Reed Crandall, John and Marie Severin, Russ Heath, Graham Ingels, Al Williamson. It was also a training ground for the greatest artists of the future: Frank Frazetta, Alex Toth, and Gene Colan all cut their teeth at EC. The Picto-Fiction magazines put them right up front with a table of contents crediting each one. The writers were often pseudonymous (we’ll get to that too) or, in Confessions Illustrated, not credited at all.

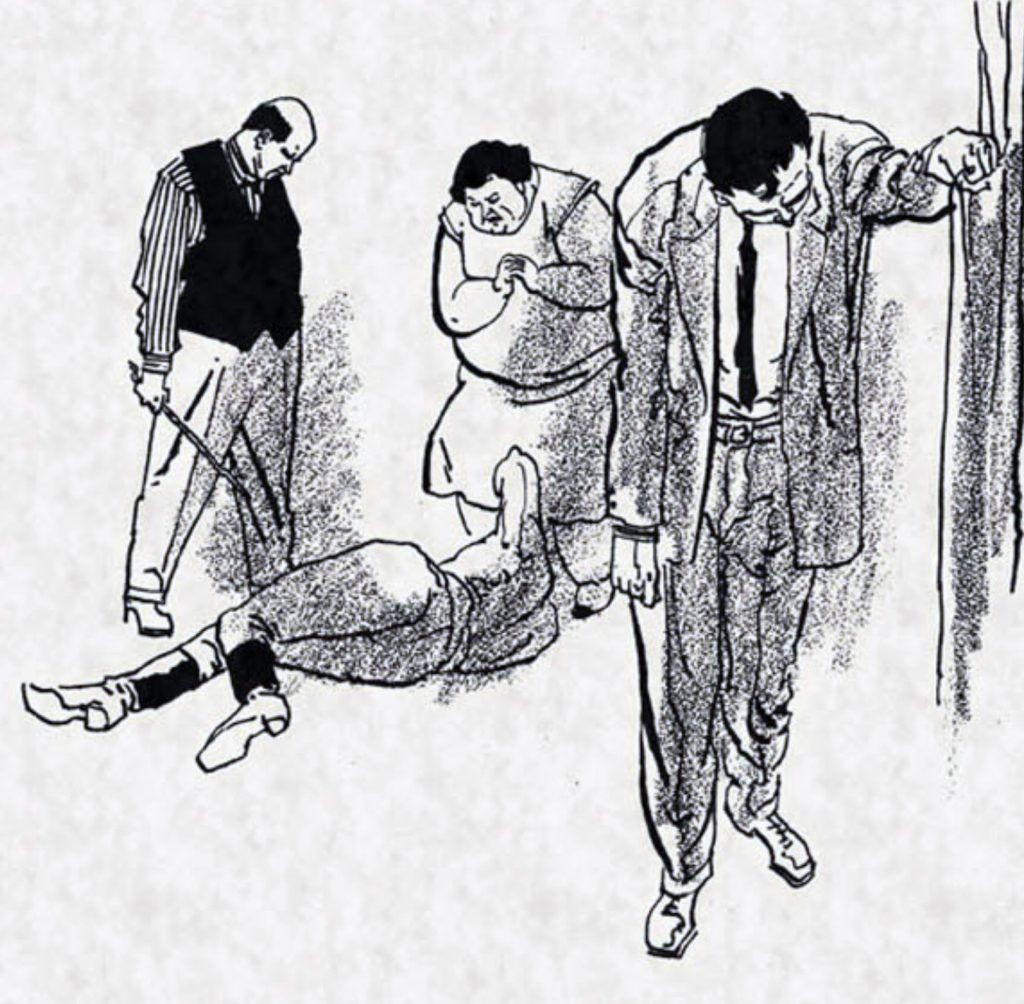

As for the artists, the transition to black and white was addition by subtraction. They lost Marie Severin’s lurid colors but their linework gained new clarity now that it wasn’t messily covered up by cheap printing. They got to experiment with all kinds of media — charcoal, halftone paper, white-out.

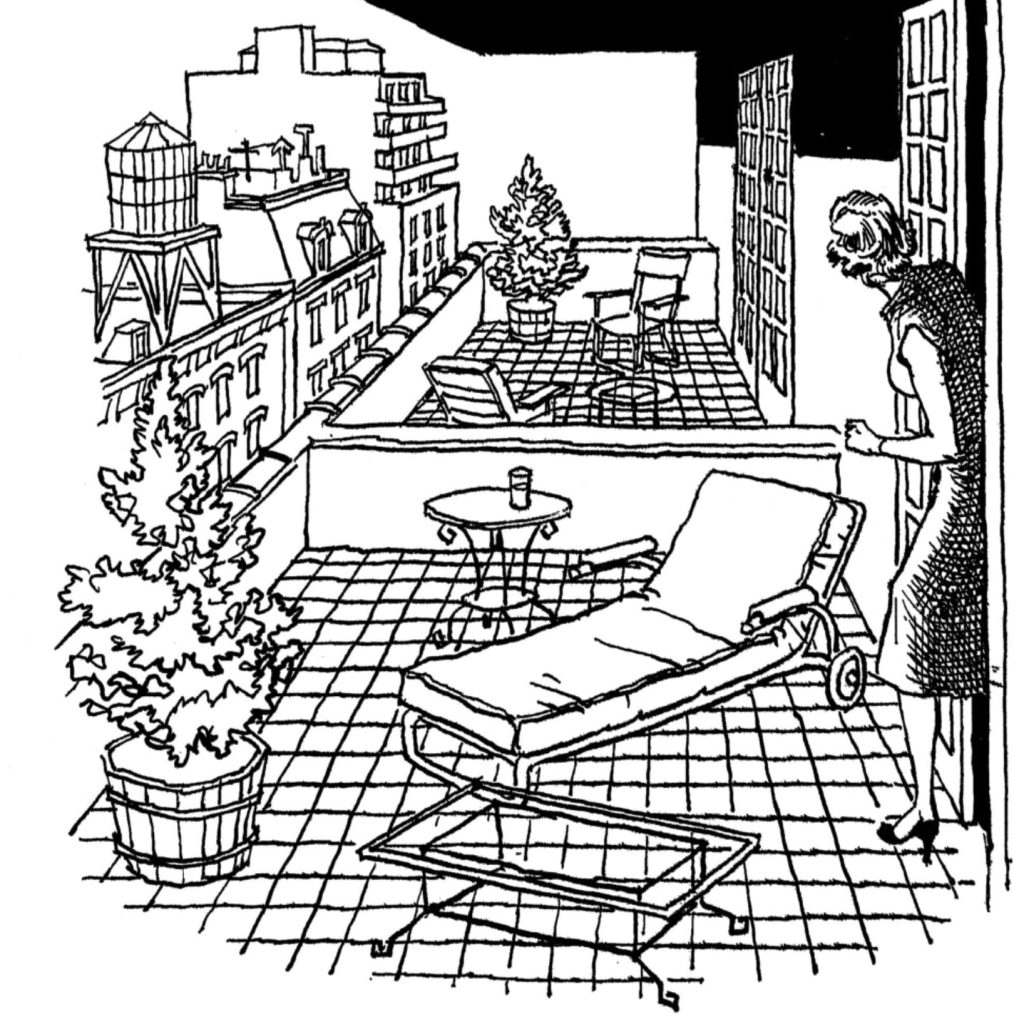

None of them took to the opportunity quite like Reed Crandall. He had already had some of the cleanest and most expressive lines in the EC catalog, but Pict-Fiction took him to another level. His enthusiasm is infectious as he uses every technique and style he can think of. His art is full of all kinds of shadow — jet black, soft grey, curves, cross-hatches, and dots. And when there’s no shadows at all, or when all that matters is the characters in the foreground, his backgrounds are sketchy or even doodly in ways that anticipate the art of ten or twenty years later.

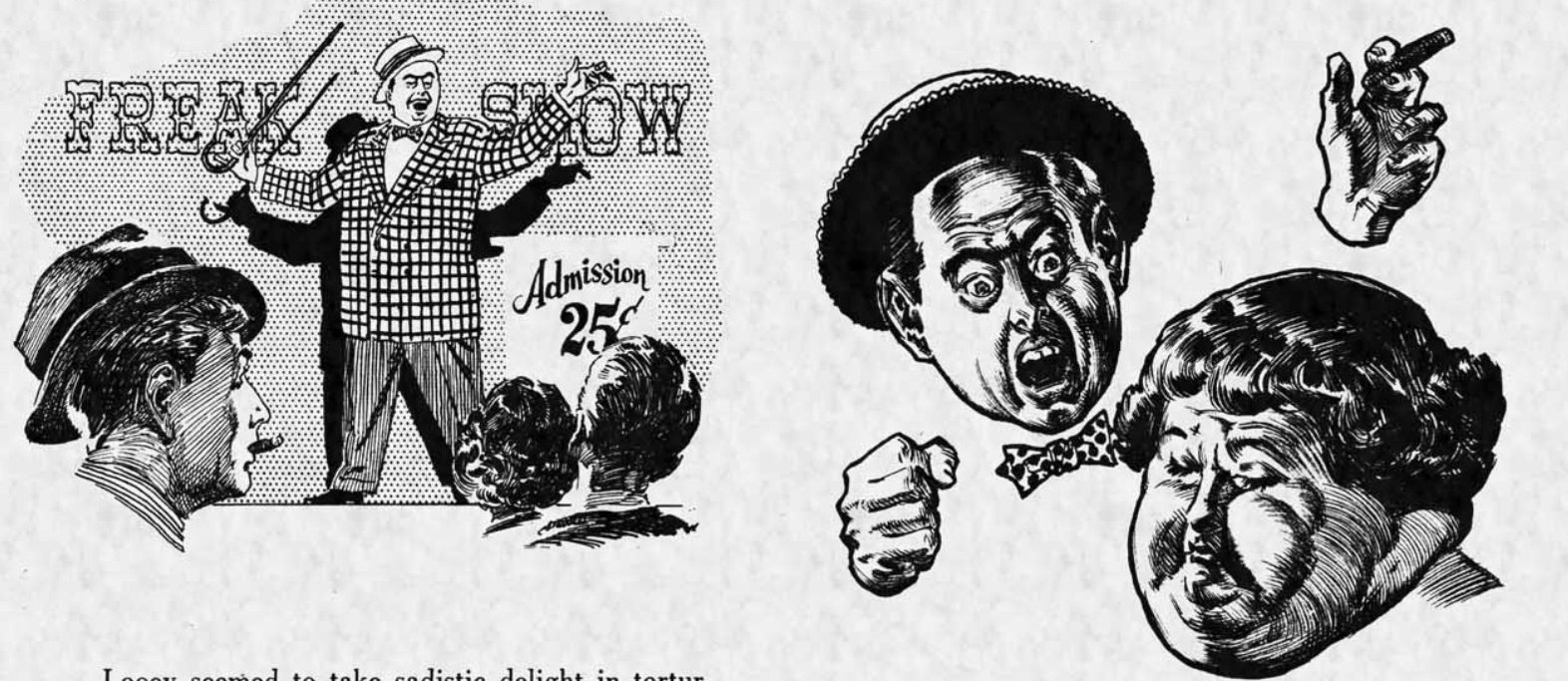

His most powerful use of this technique is in “Horror of the Freak Tent” for Terror Illustrated, where a moment of tragedy turns the whole world more abstract and the charcoal shading doesn’t even match up with the line art.

Crandall’s versatility is dizzying — he can switch from lush shading to blocky expressionism to grotesque hyperrealism within and between consecutive panels like a collaboration between Charles Dana Gibson, Milton Glaser, and Charles Burns. But it’s all him.

You can see all the artists playing off each others’ experiments and drawing from the world of commercial illustration. Instead of using line or color to define shapes, they simply let your brain fill them in.

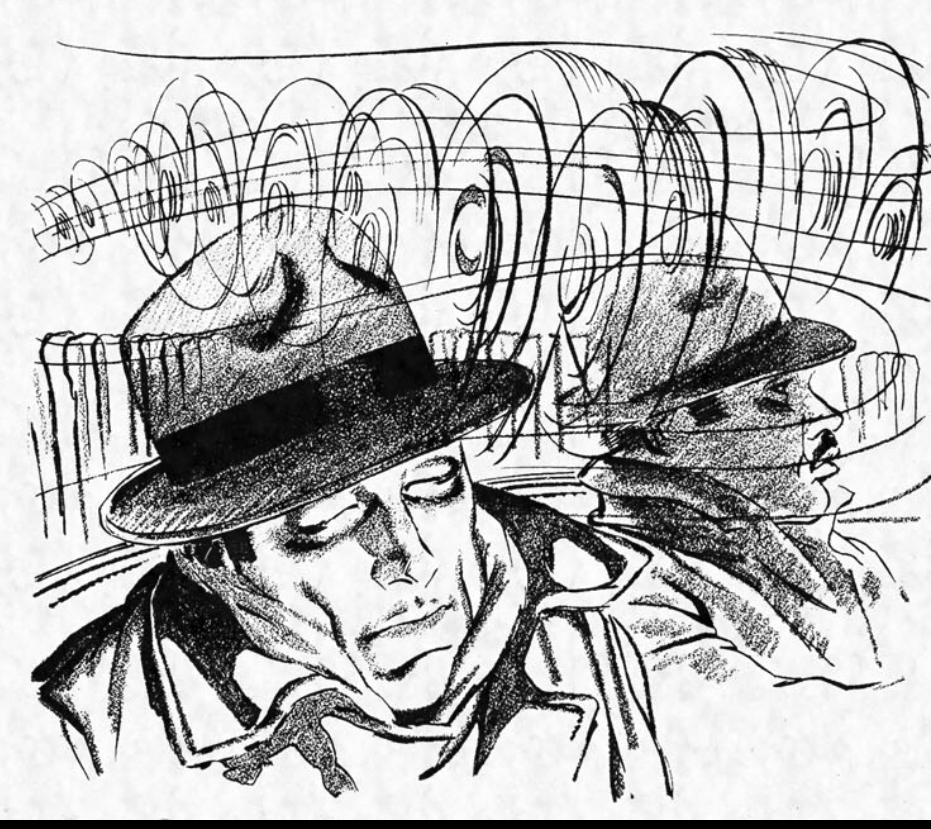

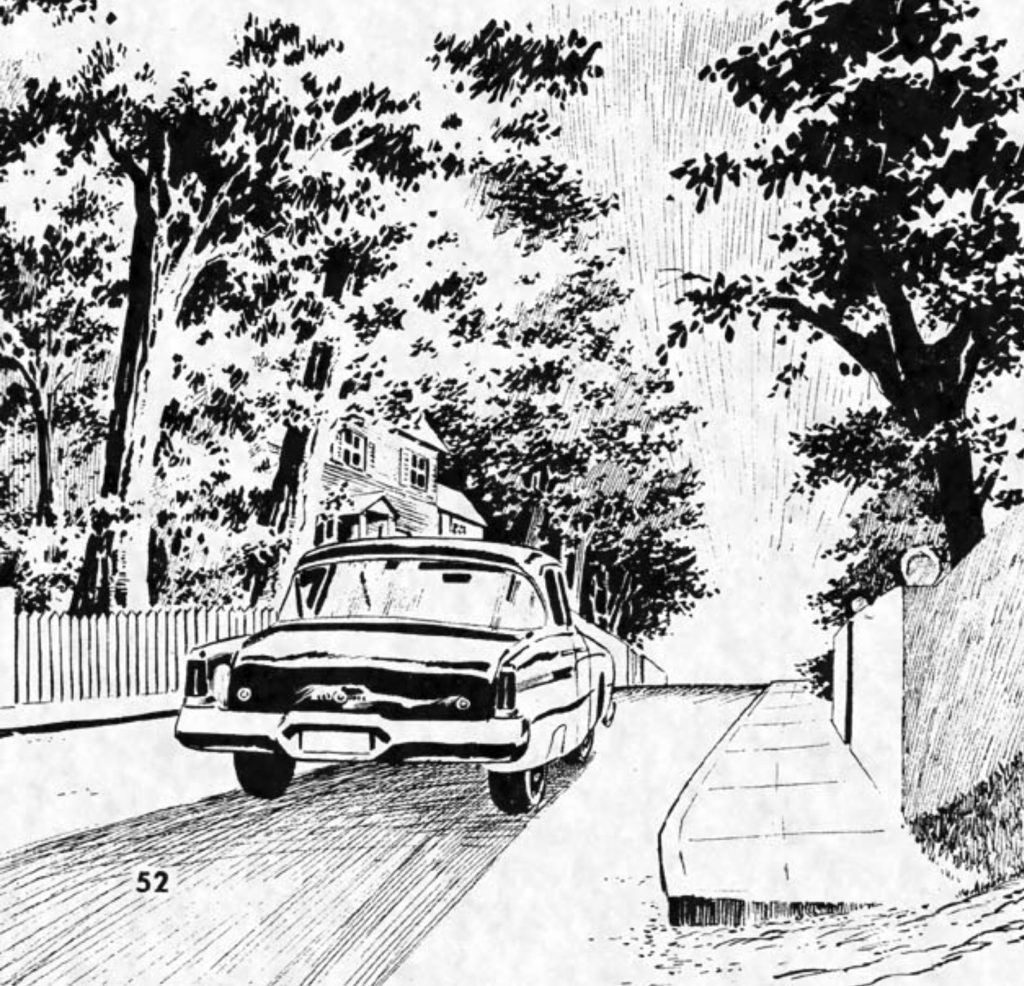

I keep staring at this art by Johnny Craig and I could swear I see the curve of the steering wheel, but he never drew it.

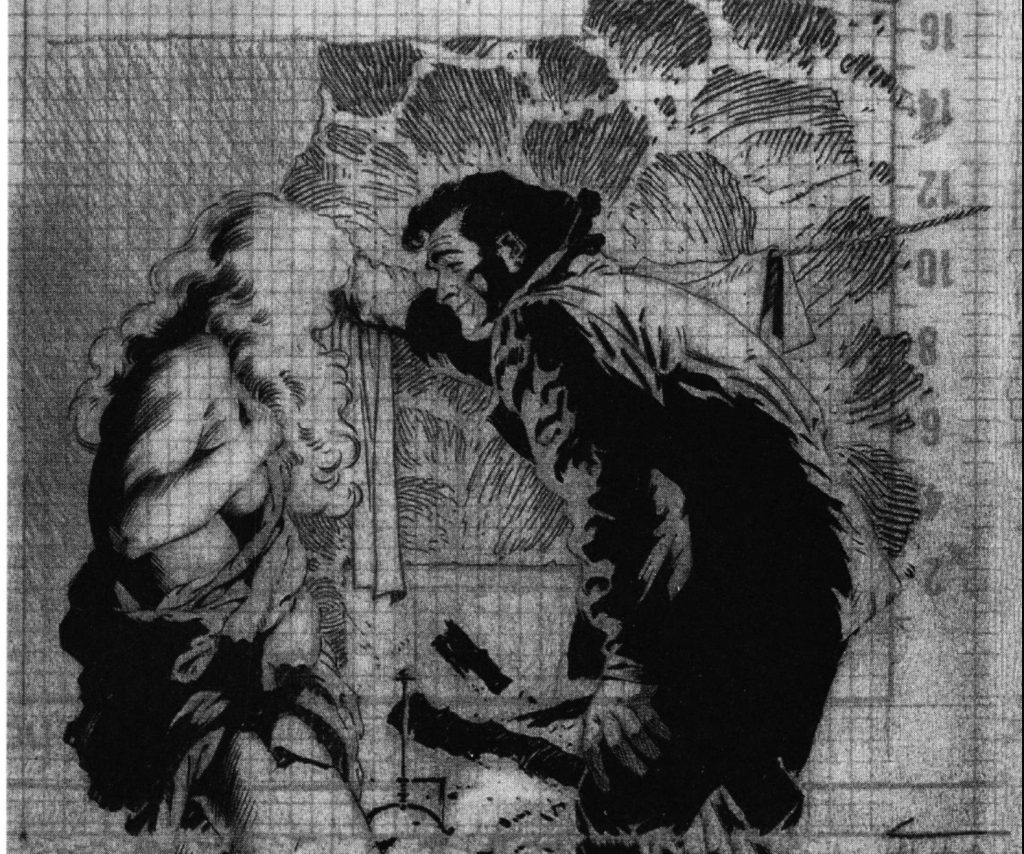

It’s probably not a coincidence that two of EC’s best artists, Davis and Frazetta, graduated to commercial illustration after this. Unfortunately, Frazetta’s one shot at Picto-Fiction was left unfinished when Shock Illustrated went under, but his sketches for an update of Wood’s “Came the Dawn” still show all the grace and energy that would make him one of the biggest names in the field. The panels he began inking show his beautiful use of clean, deep blacks, atmospheric shading, and lifelike texture.

His legendary horniness is also on full display — the female characters’ clothes are just about painted on, and the pencil art confirms the suspicion he started with a nude figure and clumsily covered it up.

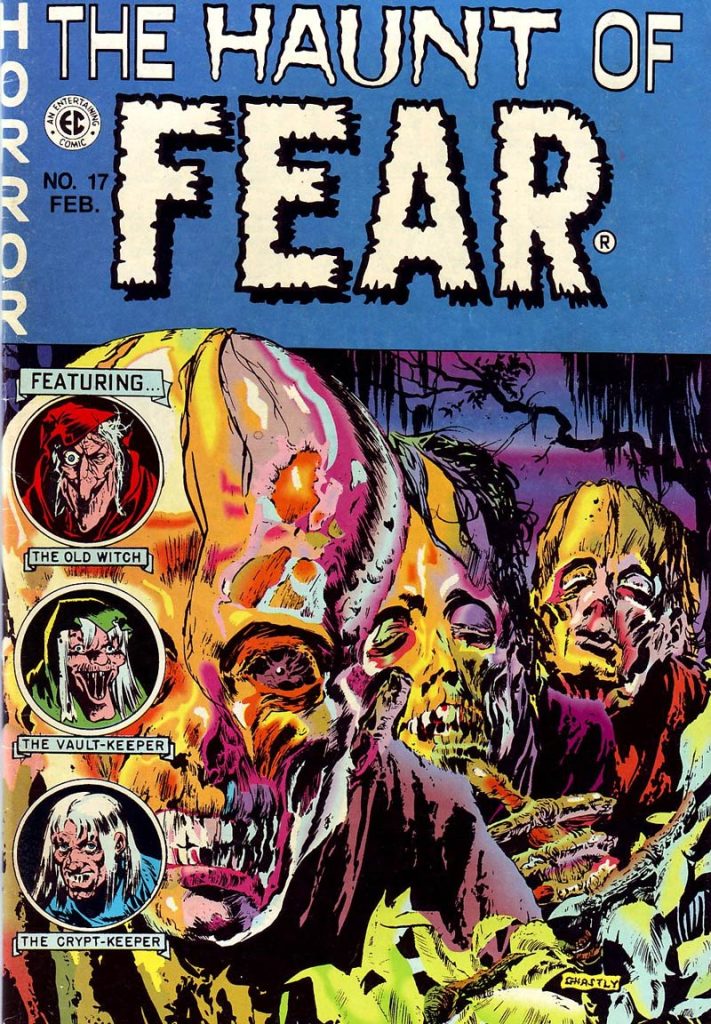

“Subtle” is hardly a word anyone would use to describe Graham “Ghastly” Ingels’ previous horror comics…

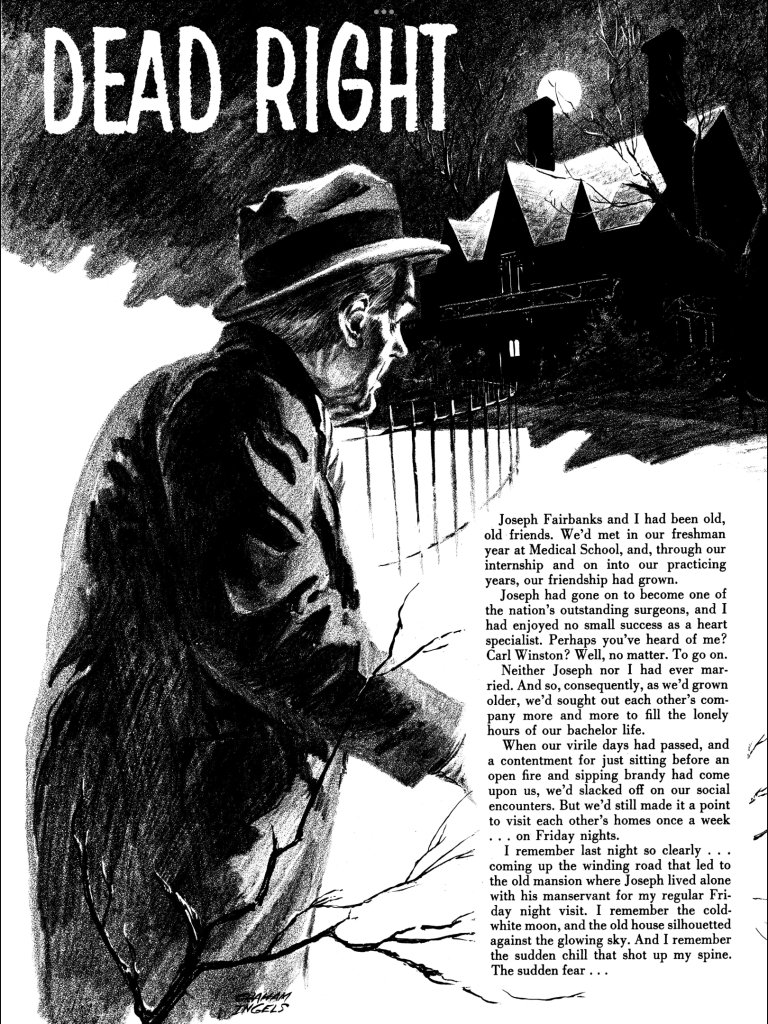

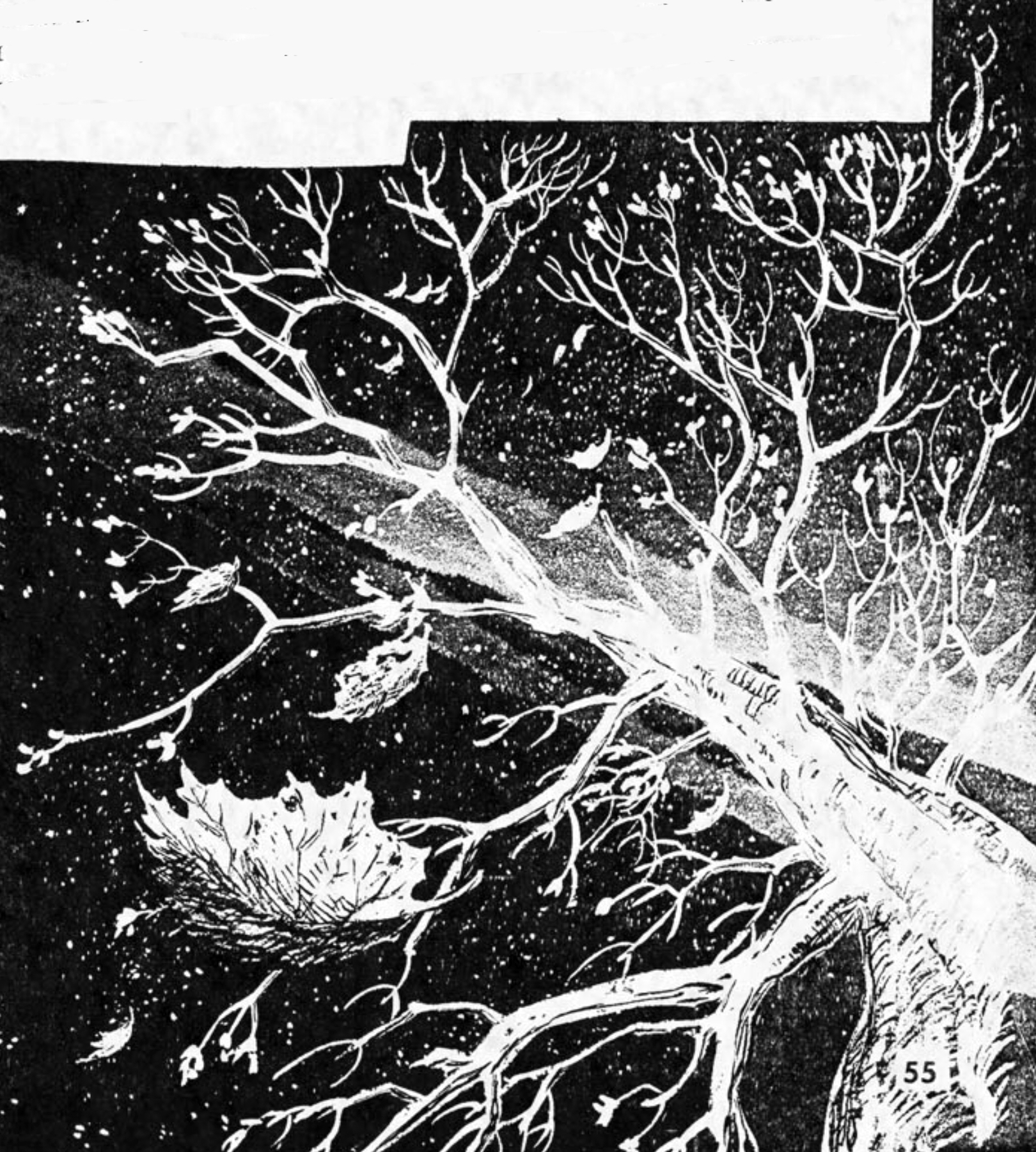

but it absolutely applies to his work on “Dead Right” (another remake, this time of a Jack Davis story from Crypt — you get the sense Feldstein saw the writing on the wall and knew it wouldn’t be worth the effort to crank out all-new material). It opens with a beautifully atmospheric full-page drawing of a scene illuminated by a full moon that seems to really glow with some careful charcoal textures.

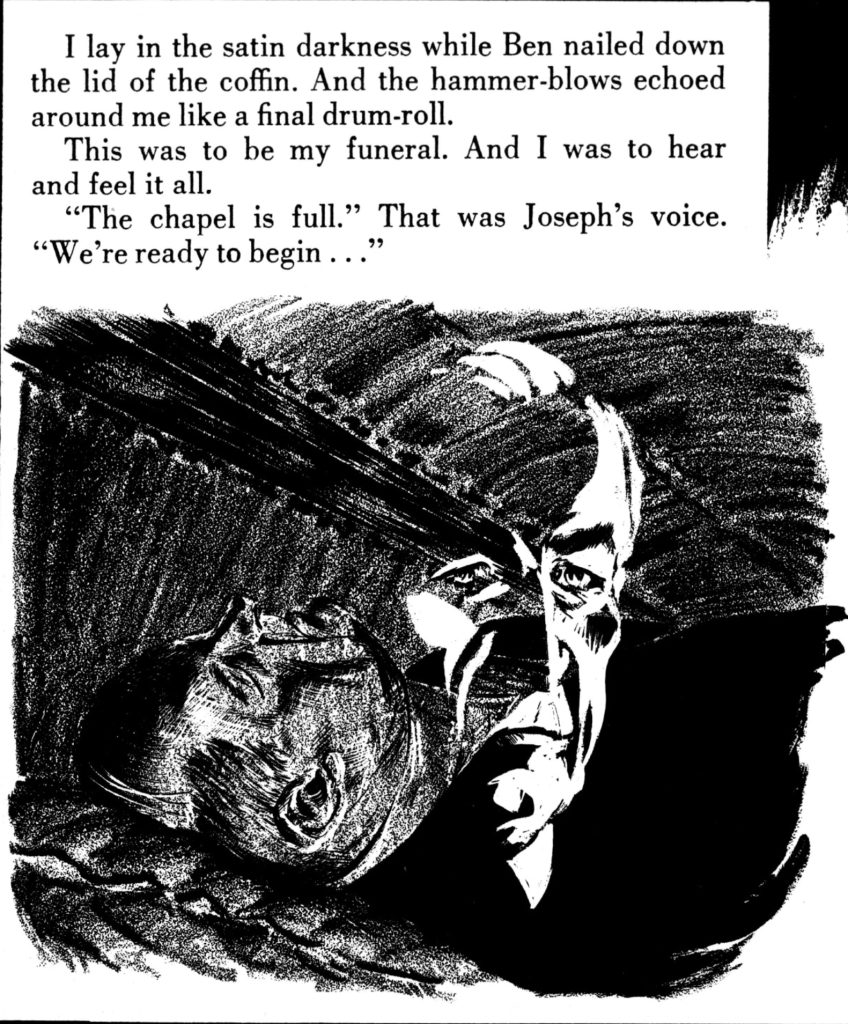

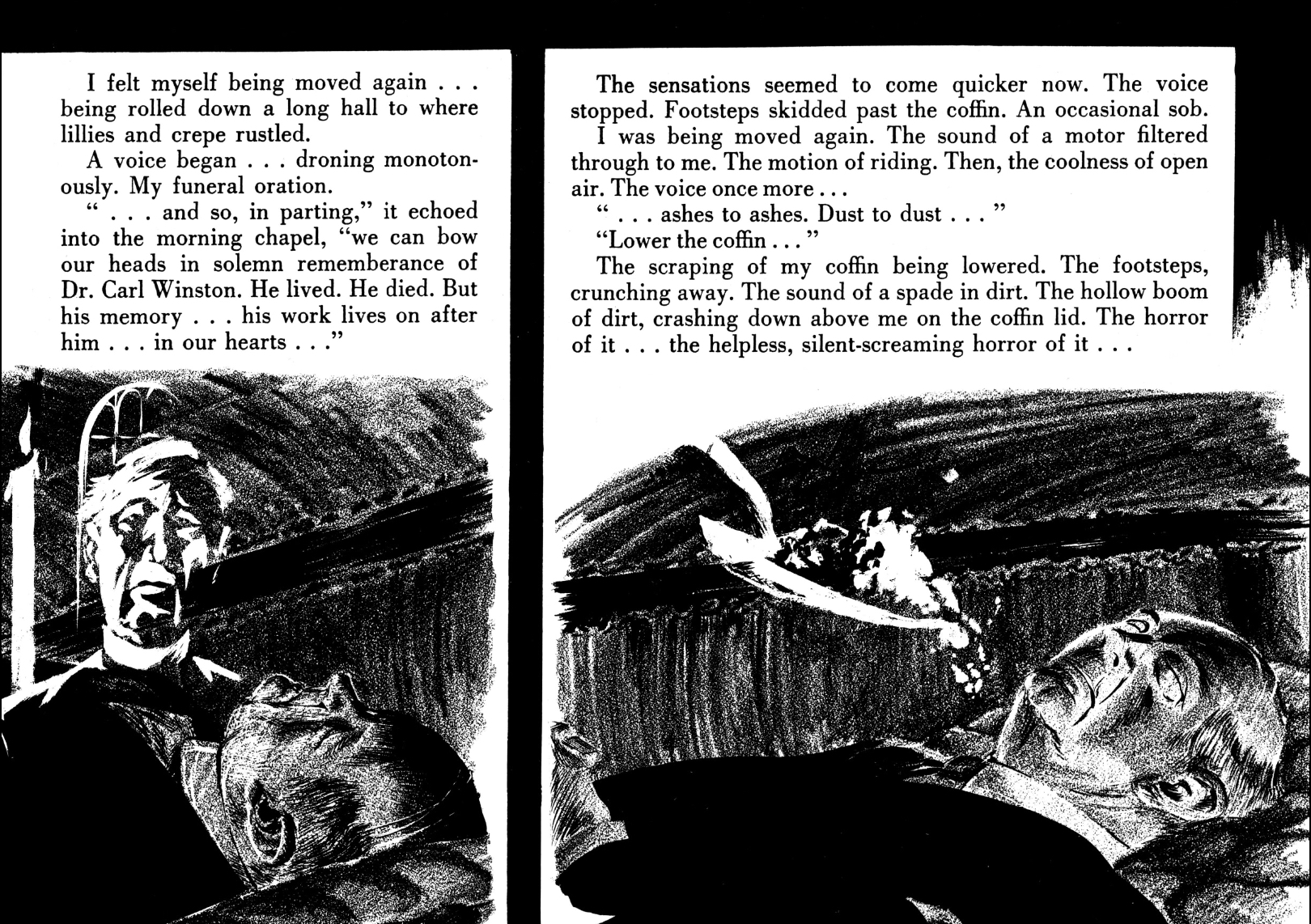

Ingels uses similar effects throughout the story before going full-on experimental, overlaying images in white over his black charcoal drawings to show the world outside the coffin as the narrator is buried alive.

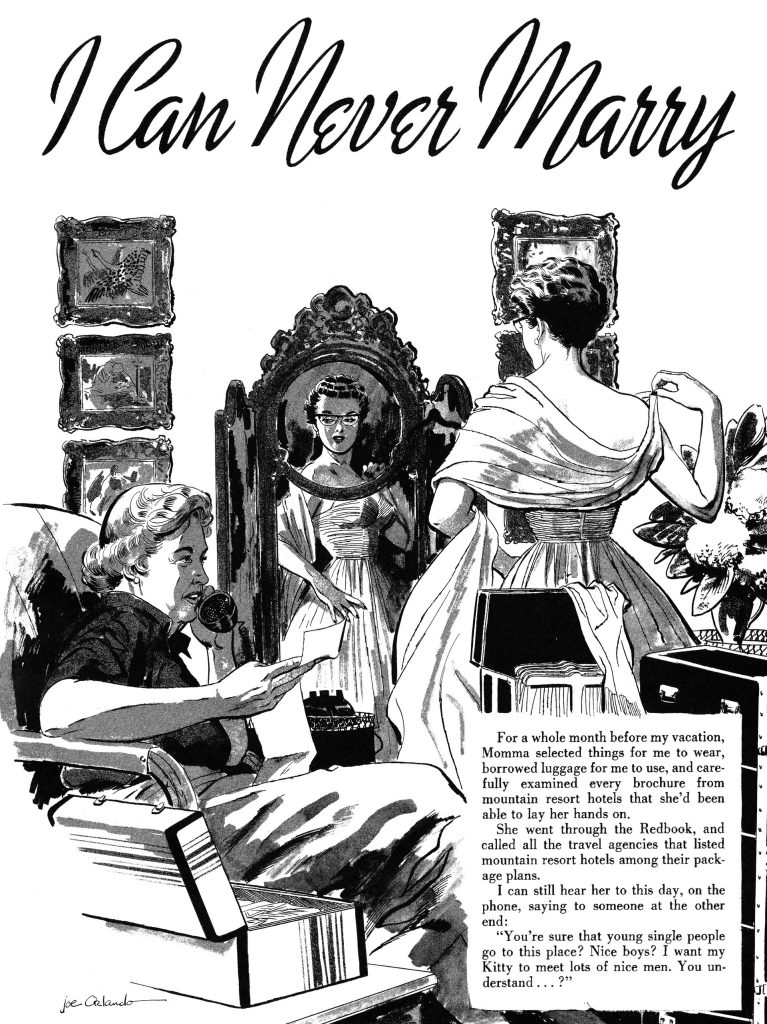

So how are the stories? Well, reading them all at once can get a little monotonous, especially in Confessions Illustrated, where each story features a young woman leaving her comfort zone and being pressured into sex and/or crime. So many of them have identical endings with the wayward wife narrating how happy she is back with her husband or fiancee the artists can’t be bothered to illustrate it. Some of it’s painfully ’50s, “exposing” the dangers of counterculture groups like teen gangs and Greenwich Village beatniks. But the subversiveness that makes the best of EC so timeless (and set off the backlash that killed it) creeps into Joe Orlando’s “I Can Never Marry,” where the one doing the pressuring is the thirty-year-old protagonist’s mother who insists she show herself off so she can land a husband before she becomes “a withered old maid.”

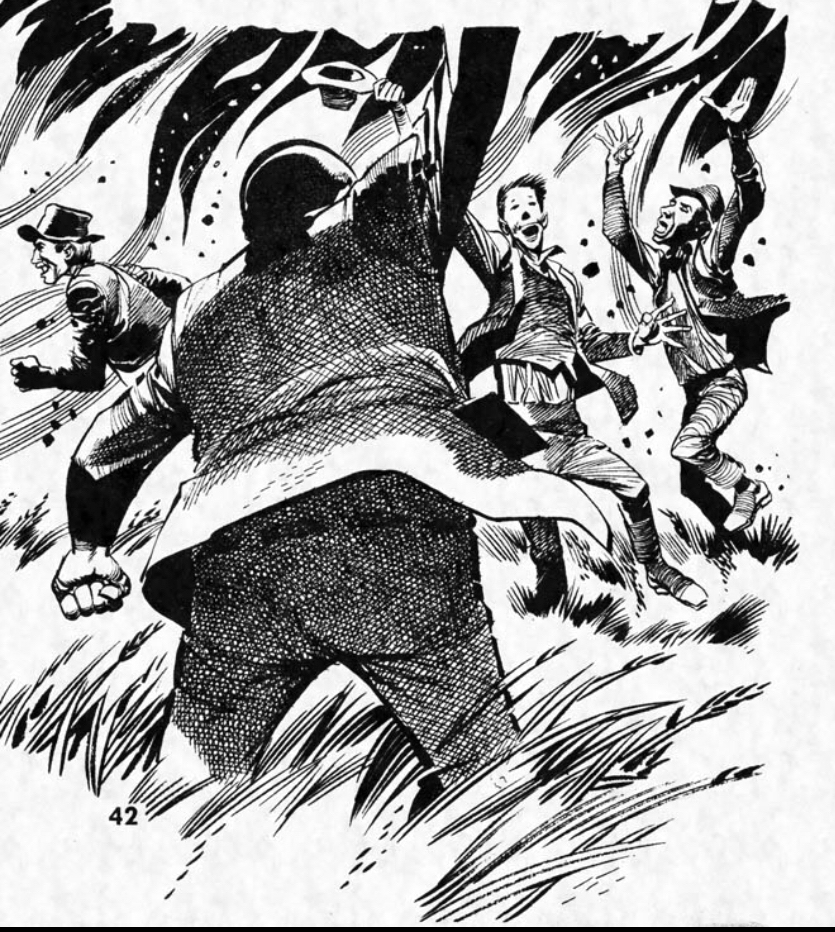

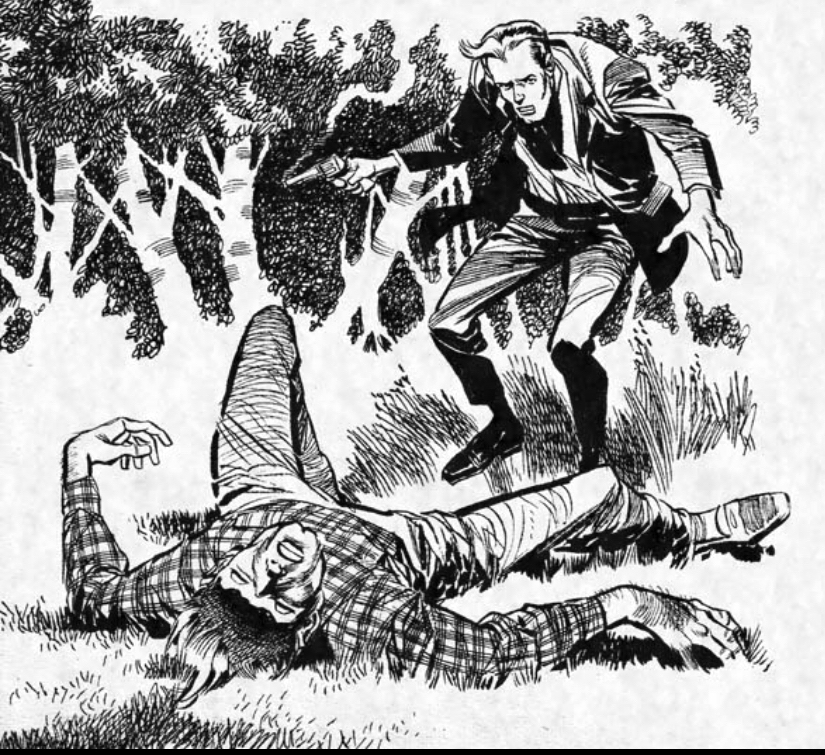

Jack Oleck and Jack Davis’s “Headman” in Terror Illustrated goes even further, exploiting our assumptions about childhood innocence for one of the most chilling of EC’s trademark twists in a story about a little boy whose mill-owner father won’t let him play with the workers’ kids, a serial child-killer, and a lynch mob led by the boy’s father.

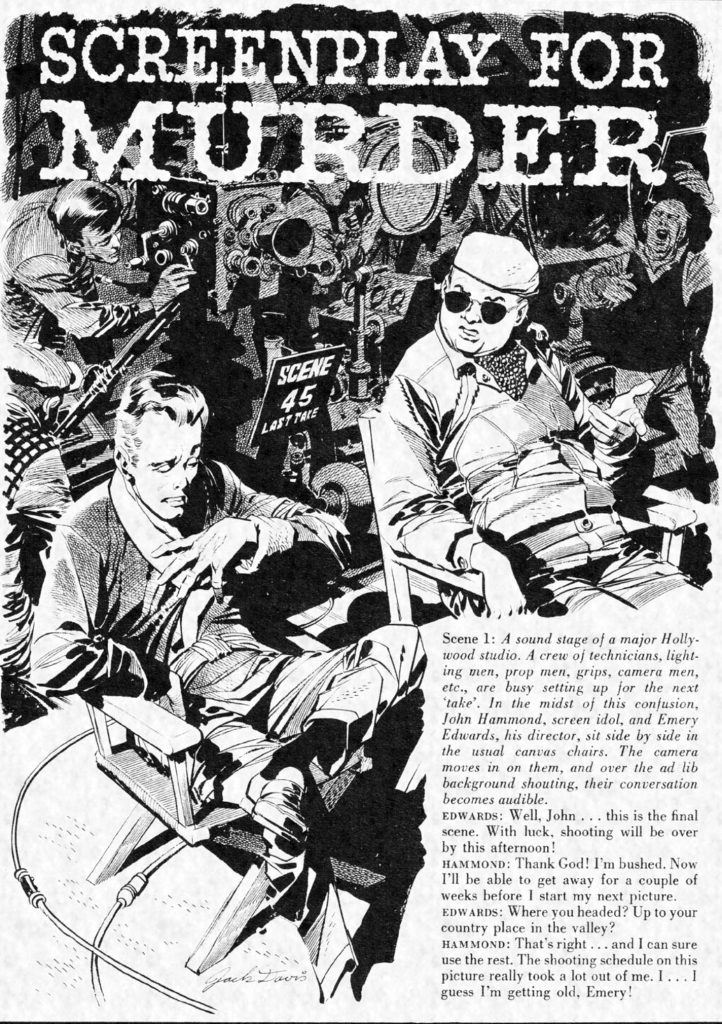

Davis also collaborates with Al Feldstein on “Screenplay for Murder,” which suggests the Picto-Fiction format could have inspired as much experimentation on the story end as it did on the art end with Feldstein’s inspired decision to write his story of Hollywood homicide as a movie script. All that, and some gruesome ironic justice courtesy of Chekhov’s lawnmower.

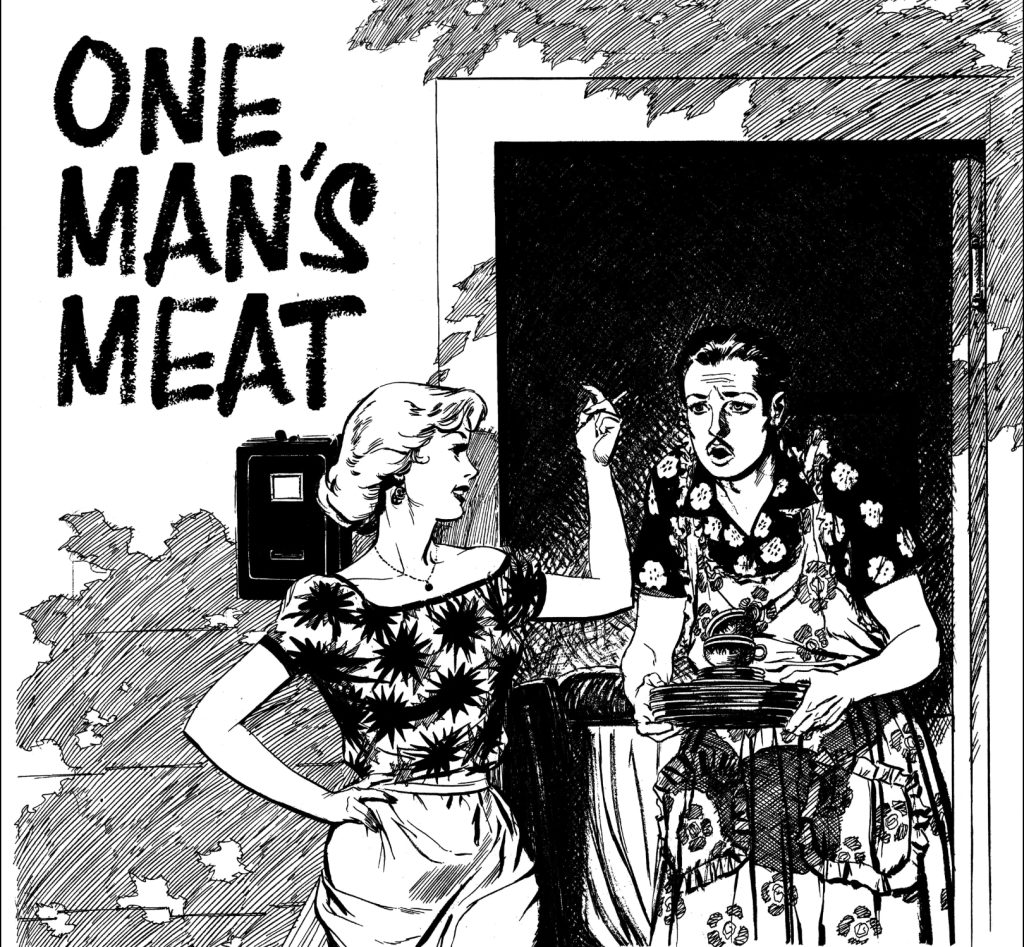

Meanwhile, other stories are so offensively dated they’re almost quaint. Oleck and George Evans’ “One Man’s Meat” in Shock Illustrated stars a clearly gay-coded man in a John Waters mustache who’s driven to murder because he’s too “effeminate” to please his wife, what with doing all the cooking and chores. Ladies, is that really such a bad deal?

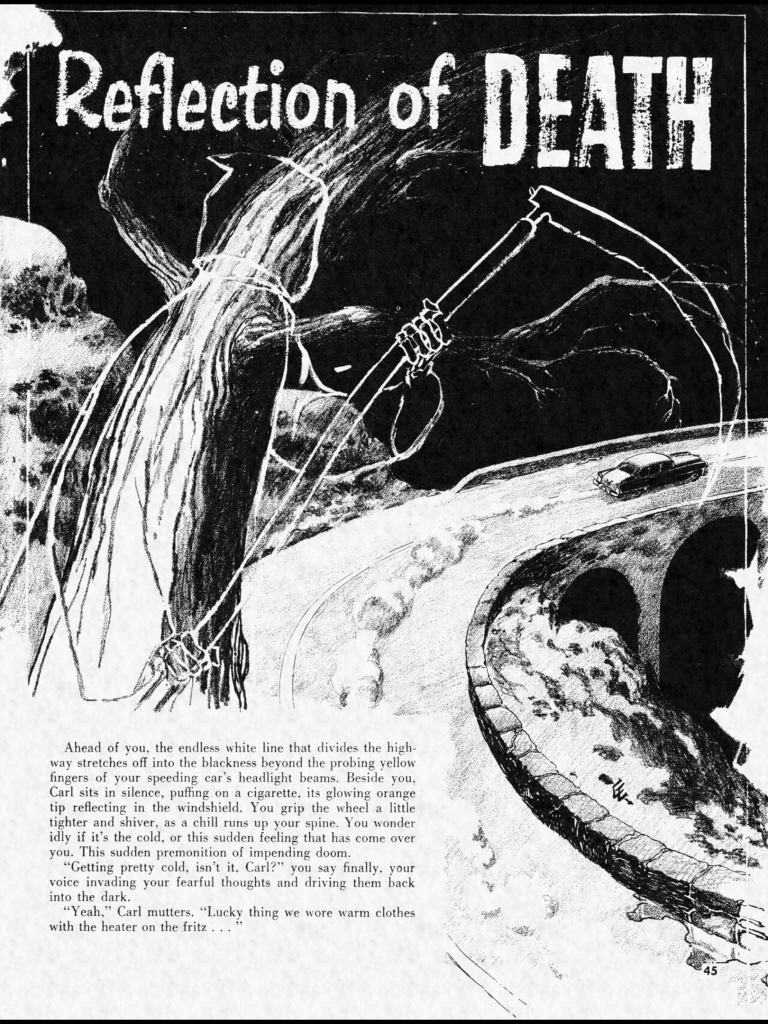

Pitco-Fiction inspired stunning work even from the artists who, at least to my mind, make up the middle tier of EC talent. Evans seems like a textbook second-stringer — prolific, dependable, but mostly anonymous. None of that stopped him from creating a masterpiece with “Reflection of Death.”

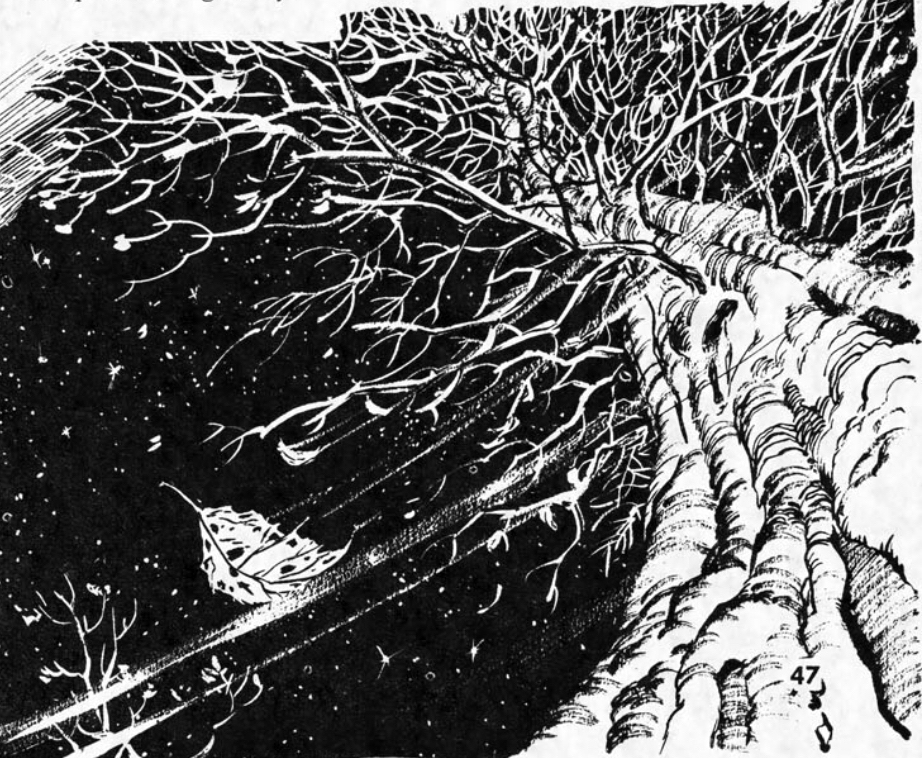

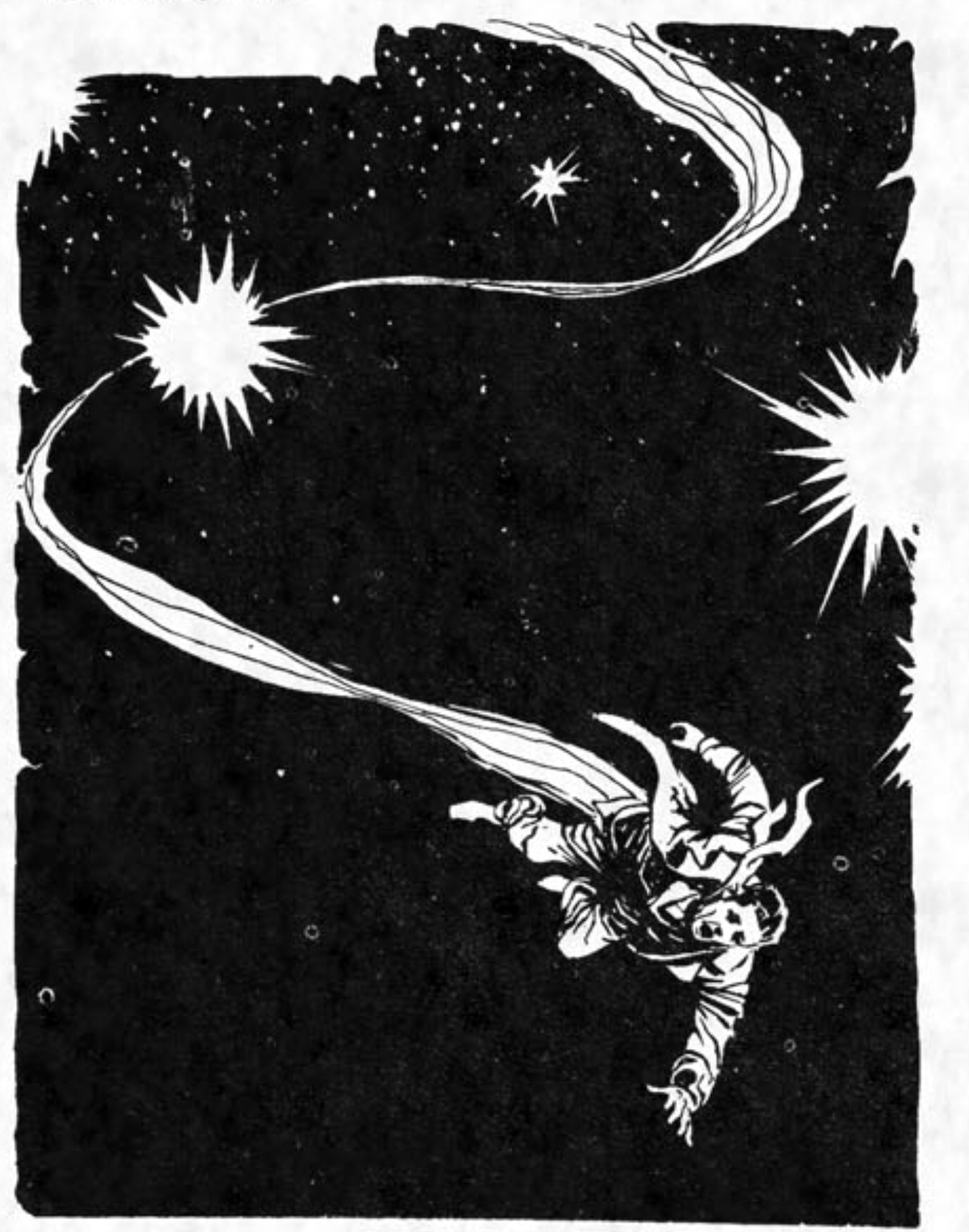

It opens with the striking image of the white outline of the grime reaper looking out over the highway and continues with more striking experiments: the protagonist floating in space as he loses consciousness. The black and grey textures of a gnarled old tree with its delicate, white-lined branches standing out against the night sky. The whole tree overlaid in white as history repeats itself. An almost Duchamp-esque montage of the characters in the car overlaid with dozens of sketchy, spinning wheels. The white rings scratched out half-tone paper around an incoming car’s headlights.

It helps that Evans is working with good material. The story of a man who wakes up from a car crash to find the sight of his face terrifies everyone he meets is as eerie as it gets, all the more so for the effective use of one horror comics’ best tricks (borrowed from radio) of second-person narration. It’s so good it’s hard to understand why the writer took his name off it — until you get to the part where he pulls out the worn-out “it was all just a dream!” bit and just keeps going.