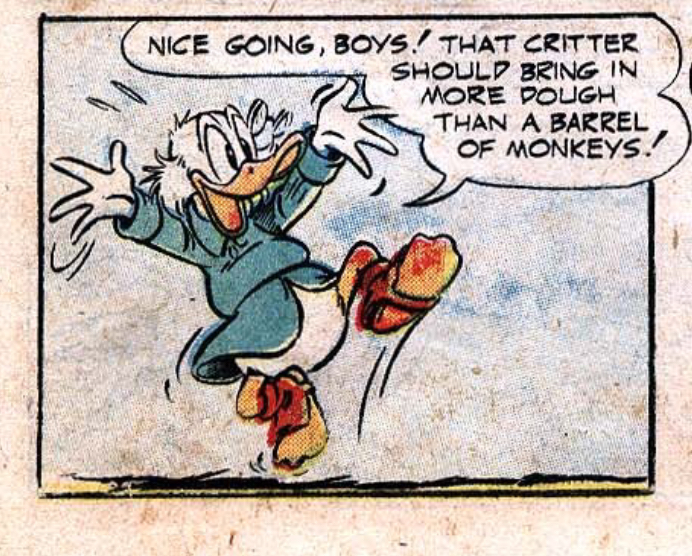

This is original artwork by Carl Barks, who created the Uncle Scrooge comics. He’s considered a bit of a genius.

— The Last Days of Disco

If John Stanley’s the unsung hero of the kid-oriented humor comics of the Golden Age, maybe that’s because Carl Barks has taken up all the space as the big fish in that small pond. He has a bit of a leg up on Stanley, since he spent his career working for one of the biggest media empires known to man and Stanley’s most famous work was based on an obscure Saturday Evening Post cartoon. Like Stanley, Barks was never allowed to sign his name. Kids in his heyday knew him only as “the good artist,” but he’s still built a worldwide cult following.

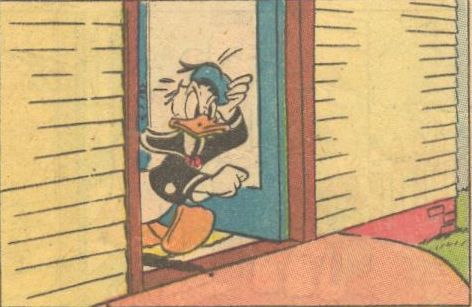

And I do mean worldwide — he’s like the prophet, not without honor save in his own country. Long after they were forgotten in the country where they began, Carl Barks’ action-hero reinvention of Donald Duck and invention of his even more adventurous Uncle Scrooge have become the most popular comics in Europe and much of the rest of the world, maybe because his blend of cartoon humor and globetrotting adventure fits so neatly alongside homegrown comics like Tintin and Asterix. Barks’ closest successor Don Rosa put it best during a visit to Sweden: “It feels like a gigantic practical joke, as if you all got together one day and whispered ‘Let’s make him think he is famous.’”

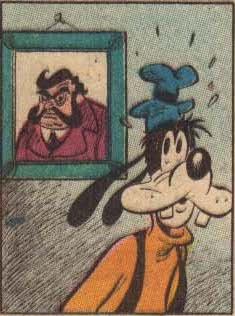

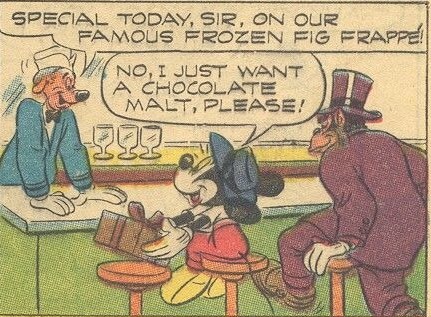

So, what makes Carl Barks the “good artist?” In researching this piece, I was able to find full scans of the 1952 issues of Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories, where I could see Barks’ art right alongside his contemporaries. They actually come off looking pretty good. Most of the other artists, like Barks, came from Disney’s animation studio, and they bring remarkable liveliness to their work that makes it look animated even on the still page. (This wouldn’t last long — a decade later, Disney comics would adopt the stiff house style of Tony Strobl.)

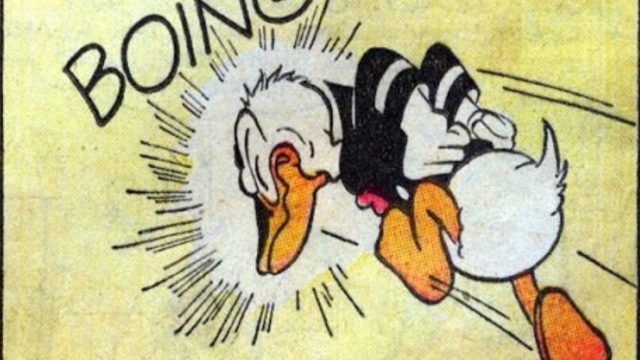

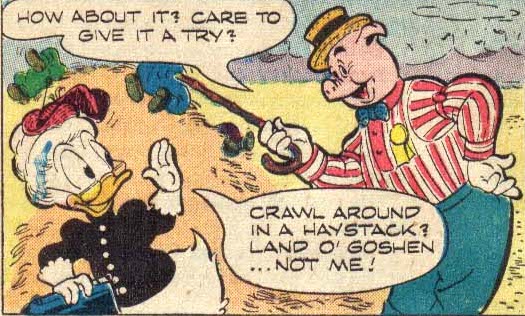

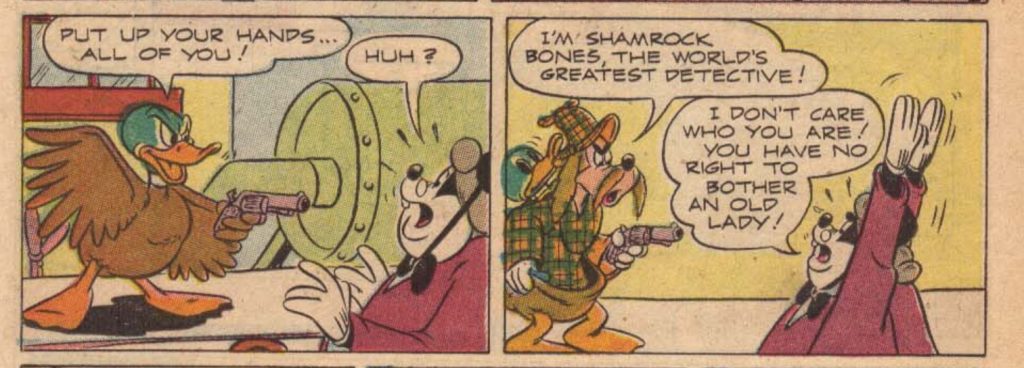

Some of these comics even made me chuckle occasionally. But Barks is something else altogether. He doesn’t fit into any kind of “house style” — these stories are loaded with original characters who fit right in with Barks’ interpretation of Donald and family but would look pretty weird in a big screen Disney cartoon. Those European comics I mentioned share more with Barks than just the combination of gags and adventure. Like Hergé and Uderzo, Barks creates a lush, lived-in world by juxtaposing his simple cartoon heroes against lovingly detailed surroundings.

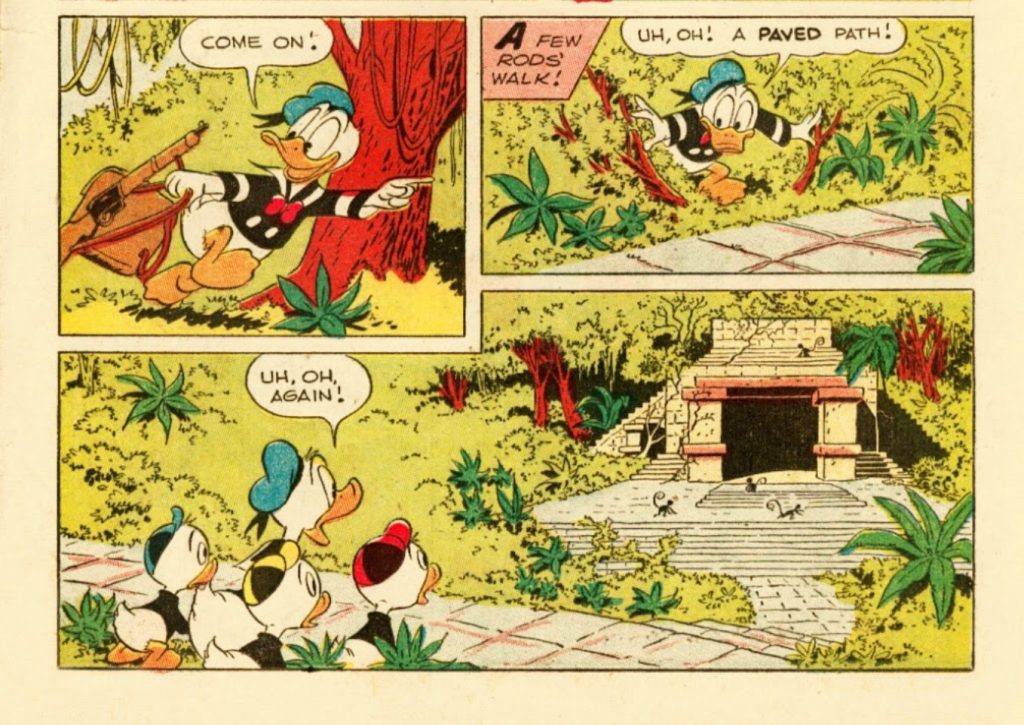

And more importantly, he wasn’t just the good artist, he was the good storyteller. These issues include some attempts by Riley Thompson and Stan Walsh to tell similar stories with Mickey Mouse, and it’s easy to see the difference. These creators don’t have the sense of pace or place Barks does. Their stories take place in a bland Anywhere, USA, nowhere near as well-realized as either Barks’ Duckburg or the far-flung locations where he’d send his heroes. Thompson’s “Shattered Glass Mystery” introduces a secret hideout in a pyramid and then does nothing with it because the story’s already almost over.

And that’s not getting into how haphazardly it’s introduced, with a travelogue, which Mickey just happens to be watching, accidentally photographing it. These stories, with plots about a conspiracy by glassmakers to slip everyone a potion that makes their laughter shatter glass or pill smugglers using migrating ducks as mules, are merely silly instead of funny. They just let those ideas sit there, without Barks’ love of absurdity, delivered, like Stanley, with a hilariously straight face.

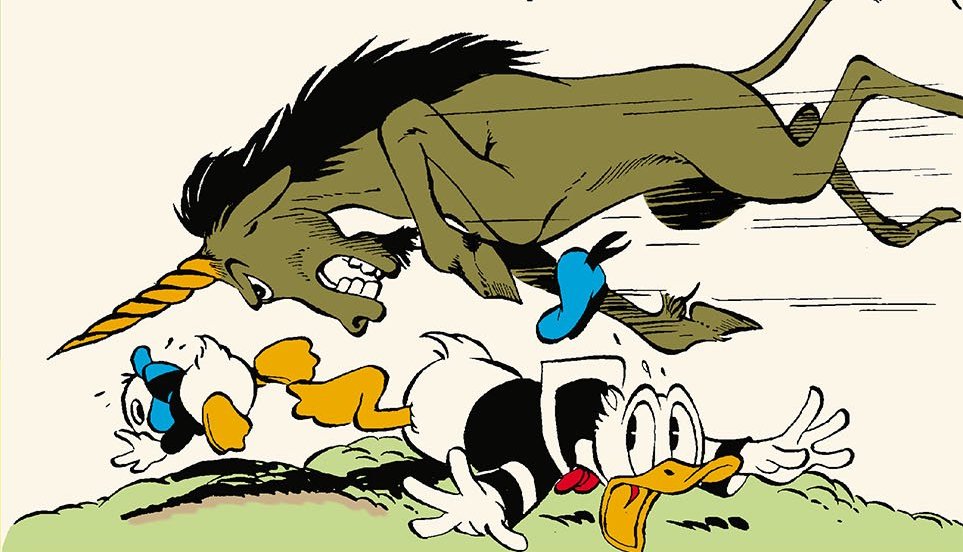

The first non-Barks issue of 1952’s new monthly Donald Duck series (continued from intermittent issues of Dell’s anthology series Four Color) also shows just what makes his work so special. In The Flying Horse Jack Bradbury and an unknown writer use a setup that’s identical to Barks’ Trail of the Unicorn: Uncle Scrooge sends Donald and his nephews to find a mythical horse for his zoo. But Barks’ story follows its own logic in a way that you can’t help but go along with it, sending the Duck Family to a vividly realized Himalyan setting and departing from the myths to create a wilder, more realistic unicorn that you can imagine could have inspired the legends of a magical beast.

In The Flying Horse, the Pegasus is plagiarized from Fantasia, and the Ducks improbably find it right in their backyard. There’s no internal logic to its existence as a creation of some local tinkerer who makes it just because the plot calls for it. And while Barks was one of the first comics writers to expand his stories from cover to cover, The Flying Horse comes and goes before it has time to make any impression.

Barks developed his own universe, separate from everything else Disney produced. 1952 marks his first Uncle Scrooge solo story and the debut of the durable wacky inventor Gyro Gearloose. That’s not as unusual in the world of licensed comics as you might think — just to look at the second-most-successful example, there’s Casper the Friendly Ghost, originally a series of threadbare Paramount cartoons until Harvey Comics expanded it into a network of Good Little Witches and Tuff Little Ghosts.

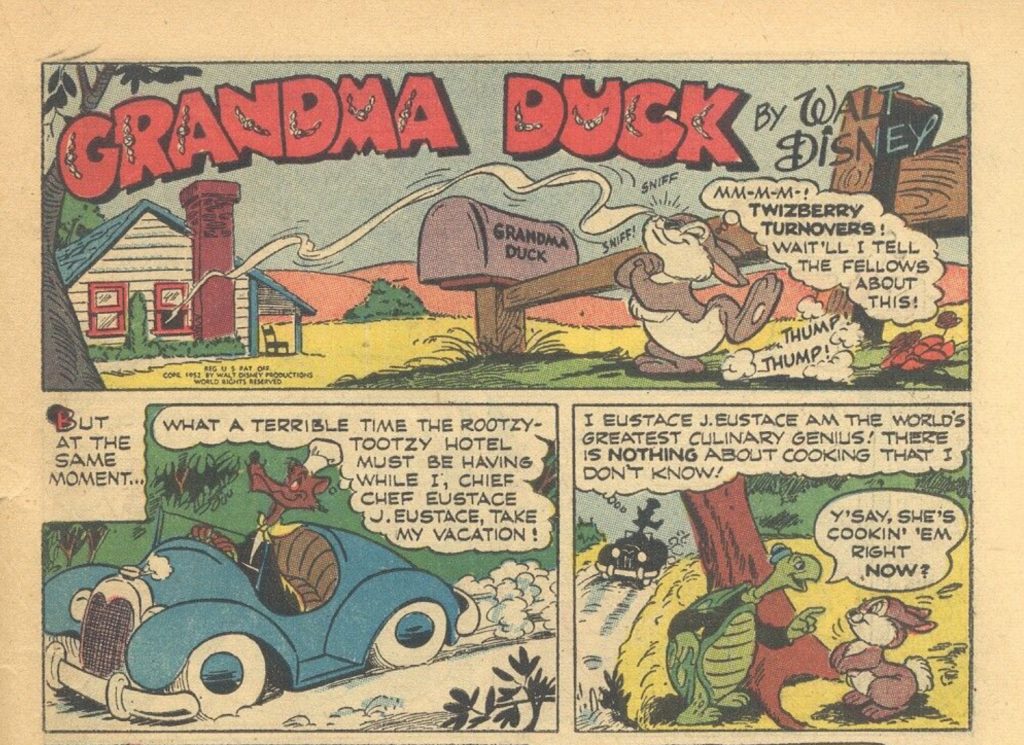

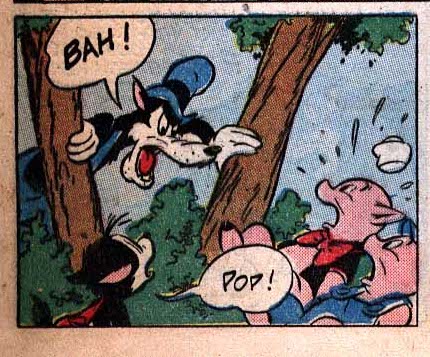

Even the rest of Comics and Stories went far afield from the source. A good chunk of their star characters, like Grandma Duck and Li’l Bad Wolf, never appeared onscreen. Barks’ contemporaries had their own (overly) complicated universe, pulling all Disney’s projects together in ways that would make Kingdom Hearts blush. Li’l Bad Wolf lives next door to the Seven Dwarfs and the cast of Song of the South. The little mice from Cinderella live on Grandma Duck’s farm, bafflingly transported from vaguely Medieval France to vaguely 20th-century America. And I can confirm that their pidgin dialogue is even more annoying in black and white. One story casually drops in a crossover between (off-model versions of) Bambi’s Thumper and the tortoise from The Tortoise and the Hare for all of one panel.

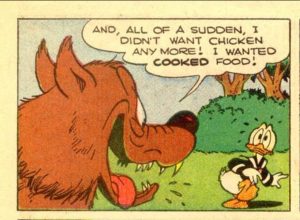

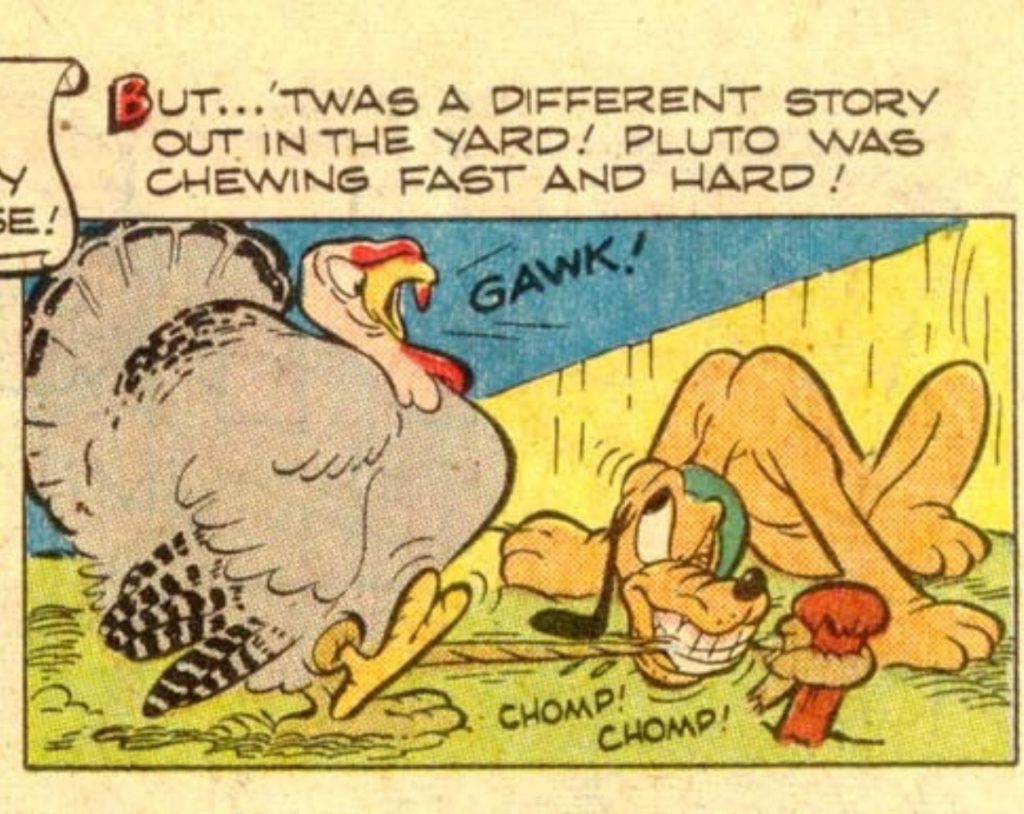

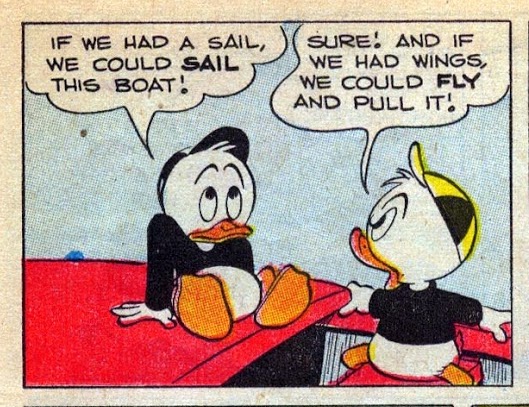

There’s a lot of confusion to reading these comics as an adult, especially with Li’l Bad Wolf, the Big Bad Wolf’s son whose best friends are the Three Little Pigs. As cartoon historian and occasional Disney Comics writer Don Markstein points out, “It was a situation worthy of the grisliest, most unspeakably gruesome horror comic imaginable — a father constantly trying to eat his son’s friends.” Even Barks, who’s admitted he sometimes forgot he was writing ducks, isn’t above a little zoological confusion.

Then there’s Gyro’s debut in “Think Boxes.” The tinkerer comes up with a device that will allow animals to talk, apparently without realizing that he’s a chicken. Just to add to the surrealism, this scene briefly acknowledges that the “human” characters are really talking animals, but that apparently only certain species of animals normally talk.

Anyway, turn the page to see the Big Bad Wolf walking, talking, and cooking without any technological aids, kiddies!