Something I forgot about the famous exchange in The Fugitive is that when Richard Kimble (Harrison Ford) tells Sam Girard (Tommy Lee Jones) “I didn’t kill my wife!” Girard doesn’t immediately say “I DON’T CARE!” He has a moment of genuine shock that Kimble would think this really matters, that this would make the U.S. Marshal stop what he’s doing. The line is famous because its funny and unexpected but also because it cements how The Fugitive is about roles and goals coming into conflict with each other. Kimble is trying to find the true killer but also surviving, avoiding capture as long as he can (after all if he gets caught it’s lethal injection). Girard however is a Marshal and what that means is that he hunts down men like this every day of his life, and he’s very good at it. As he says, “I. do not. bargain” and he does not compromise. Andrew Davis’ 1993 film depicts how these two men must meet in the middle for justice to happen – Girard may not compromise but Lee Jones subtly depicts how his belief in Kimble’s guilt disappears, and Kimble becomes less concerned with running and more with vindication. The film works so brilliantly because it shows a journey towards mutual understanding, the point where Girard doesn’t quite bargain with Kimble as much as empathizes.

But there are many, many reasons The Fugitive is so good. Its a thoroughly Midwestern, Chicago film in locale and tone: while some of the flashbacks are more glossy (which makes sense stylistically), the film is to the point, does exactly what its supposed to do. The main characters exist in the waters, the cold, on the streets, slipping in sewers and struggling for leverage over those who would see them in prison or incapacitated. The Marshals work out that Kimble’s back in Chicago when they hear an L train; in a remarkable chase Kimble slips away from Girard, only a few feet behind, in the St. Patrick’s Day Parade, slipping off his coat and barely getting past the barriers. Giant set pieces and tight pursuits interlap. The glorious one take train crash (why does it feel so enormous? Because it is a real train coming down that track) leads into the absurd moment where Kimble steals an ambulance and is besieged by Marshals and cop cars. This is an almost pure genre piece that allows just enough subversion to never be tedious on a writing level (observe Kimble calling the Marshals from the one armed man’s house and leaving the phone off the hook so they’ll track the location – its a great plot beat but also shows how Kimble wants Girard to see he’s not guilty).

The Marshals are the perfect contrast to Kimble here. Where Ford is haunted, nearly silent in his dogged pursuit of the one-armed man, the Marshals are chatty, weird, hyper-competent, entertaining themselves. These are people who are good at what they do and are used to working with each other (Girard asks one of the team to get him a chocolate donut and you get a sense he’s done this many times before). The script contrasts these different modes of work and professionalism, showing how the Marshals collaborate, spitball, while Kimble uses friends for help but has to rely on himself, using everything he has to press on and find the truth.

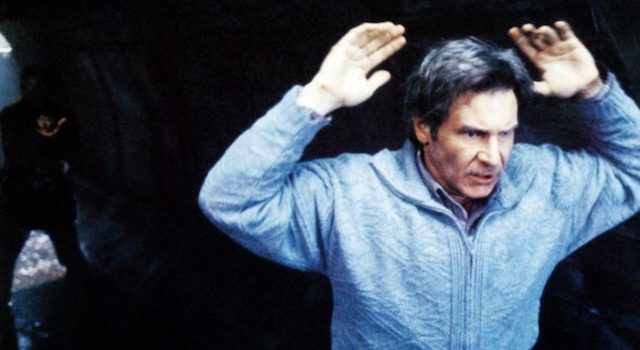

Ford in particular brings to the table a sense of pure determination. Kimble is a smart man who has shoved everything else to the back of the mind, only fueled to prove that he’s an honest man (the power of the Wrongfully Accused man trope I think is that we always want people to believe us), and to avenge his wife. When he snaps back into Surgeon Mode taking care of a kid on the gurney its like he’s coming back to a part of himself he’d forgotten, and it rings true to the films theme of professionalism versus necessity. I’d forgotten in particular how good Ford is at being a movie star, that sense of charm and confidence, and one of the joys of the movie is seeing him and Lee Jones, never more casually funny in his cruelty and cold attitude, work together. The third act with the two villains deals with them so swiftly that it could feel anti-climactic but the movie knows that the central relationship is what’s important here (though my biggest critique is that the big reveal still feels convoluted). When Girard unlocks Kimble’s handcuffs it’s just the right ending. He had to bring him in not as a prisoner, but as the man he was. In the pursuit they have gained a respect for the other’s nature.