Describing an artist as a visionary is almost a cliché, but if there were anyone who lived up to the title it would be Gram Parsons, the creator of Cosmic American Music: a blend of country, soul, and rhythm and blues, with a rock attitude. A trust-fund kid from Florida who helped to turn the Southern California scene onto the sounds coming out of Nashville and Bakersfield, Parsons first talked his way into the Byrds, overseeing one of their finest records, the countrified classic, Sweetheart of the Rodeo (1968). Then he teamed up with Chris Hillman, from the Byrds, to form the Flying Burrito Brothers. “Sneaky” Pete Kleinow, pedal steel guitarist extraordinaire, and Chris Etheridge, who earlier played with Parsons, completed the band lineup.

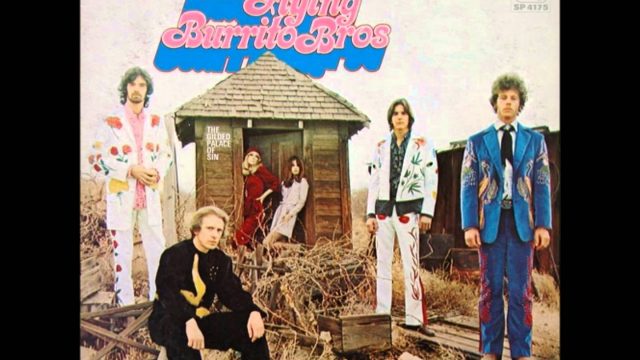

On the cover of their debut album, The Gilded Palace of Sin, the band all wear Nudie suits, custom-designed outfits made fashionable by country performers. Parsons’ suit has marijuana leaves and pill capsules on the front, and on the back (hidden from view) a Christian cross. There’s no better way to depict his status as both an insider and outsider, having the decadent habits of his social circle, yet attracted to a spirituality largely alien to it.

The first song, a nasty put down of a female groupie, “Christine’s Tune,” embodies the band’s signature sound. Written by Hillman and Parsons, it layers Hillman’s high harmony over top of Parsons’ twangy voice. Kleinow adds a spacey touch, his lead lines swelling with echo in the verse and wailing with fuzz in the chorus.

Yet this song feels practically lightweight when followed by the slower and heavier “Sin City.” Written as a traditional country waltz, Hillman and Parsons conjure up some rather striking imagery to describe LA’s day of reckoning:

It seems like this whole town’s insane

On the 31st floor, a gold-plated door

Won’t keep out the Lord’s burning rain

They proceed to dip into the R&B well, with covers of “Do Right Woman” and “Dark End of the Street.” While Parsons more than acquits himself, singing tenderly on “Do Right Woman,” “Dark End of the Street” is one of his finest vocal performances on the record—never forcing the feeling of pain over a clandestine love affair, Parsons’s phrasing at the end of the song sounds like George Jones, a country singer he particularly idolized.

In “Wheels” and “Juanita,” Hillman and Parsons flip the script on the first two songs. “Wheels” is a meditative and honest search for salvation, with Kleinow’s distorted pedal steel guitar revving like an engine. “Juanita,” another sublime country waltz, is about a girl who, as Parsons sings, “brought back the life/That I once threw away.”

That glimpse of light is swallowed up by the shadow cast by “Hot Burrito #1,” a brokenhearted country ballad, written by Etheridge and Parsons, with the stinging line, “I’m the one who showed you how/To do the things you’re doing now.” A lady killer known for turning on the Southern gentleman charm, Parsons doesn’t have to dig very deep in his own past experiences to express the desire and longing for someone whom he mistreated and needs back in his life. “Hot Burrito #2,” also written by Etheridge and Parsons, rides a groove that could’ve come from a Motown single—Parsons is past the point of pleading when he busts out in the chorus, “You better love me, Jesus Christ!” The diving and twisting pedal steel guitar runs further heat up the desperate mood, which, at the same time, is made sexy by Parsons’ vocal inflections.

No one was making records in 1969 like The Gilded Palace of Sin, and like so many visionary releases, it sold poorly. Parsons continued to cultivate his hipster cred, and fell in with kindred spirits, the Rolling Stones, leaving behind the Flying Burrito Brothers (their second record, which he was on, paling in comparison with the first). His life unraveled like a character in one of his songs. Being friends with Keith Richards did anything but help him become a more prolific songwriter. He preferred to spend his time partying with Richards, being able to pay his own way to follow the Stones to France for their recording sessions for Exile on Main Street (1972), which has a sustained feeling of country soulfulness they would never again achieve.

Parsons only made two more albums, but the second, Grievous Angel (1974), has a relatively older and sadder outlook that further enriches songs like the desolately dramatic “$1000 Wedding.” His self-destructive tendencies were little reduced after the recording sessions. In a celebratory mood, Parsons took it way too far, dying of a drug overdose in 1973 before Grievous Angel was even released. He may have idolized George Jones but lacked his longevity, checking out before the age of 30. In a bizarre chain of events, Parsons’ road manager, claiming he was acting on Parsons’ own request, stole the body after the funeral and cremated it in the Joshua Tree desert in California.

As for the fate of his Cosmic American Music, Parsons had to bear the indignity of watching the Eagles strip his creation of its parts to manufacture pop hits. In 1972, he wrote, “I’ve developed some sort of rep for starting what I think has turned out to be pretty much of a country rock dry f-ck.”

Emmylou Harris, who got her start singing harmonies with Parsons following his departure from the Flying Burrito Brothers, helped to keep his legacy alive by performing his songs during her own, far more successful, career. Harris contributed to the founding of Alternative Country, a far-ranging genre that includes Steve Earle, Uncle Tupelo, and Ryan Adams.

The Gilded Palace of Sin is a late-night listening experience that you’re more than likely will find irresistible. Not only does it give off a languid, sultry heat like few other records; it travels the heartbreak highway that runs through Southern California–in search of the secret soul of LA.