I’m very interested in the cultural work films do, that is, how the conditions of their production help to shape how they are received. It is indeed an especially critical matter in films whose reputation proceeds them, All the King’s Men a prime case. On the one hand, All the King’s Men is a timeless story about the abuse of power by a corrupt politician, Willie Stark. On the other, the film makes rather telling references to a historical figure, Huey “the Kingfish” Long, governor of Louisiana and the state’s senator in the mid-1930s, who was assassinated in 1935. His slogan: “Every man a king.”

A year before Long’s death, Robert Penn Warren, who wrote the novel of the same name, on which the film was based, was teaching at Louisiana State University. He said, “If I had never gone to live in Louisiana and if Huey Long had not existed, the novel would never have been written.”

The film follows the 1946 novel, which won the 1947 Pulitzer Prize, in navigating the always fraught connections between myth and history. Penn Warren created a larger-than-life persona of evil out of the historical circumstances surrounding Long’s rise and fall. The pertinent question that comes to the forefront: what kinds of liberties may Penn Warren have taken with these historical circumstances—and to what ends?

Keith McCrea argues:

There is more to Huey Long than the yokel turned strutting demagogue All the King’s Men shows us and, while one can’t necessarily fault director-producer Robert Rossen with omitting them (he was a film-maker, not a historian), those omissions ought not be overlooked.

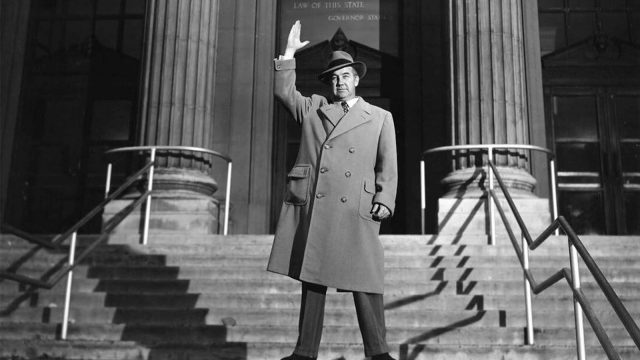

This argument can be easy to miss, lost in the Academy-Award-winning performance of Broderick Crawford, who, as Stark, gives us an indelible portrait of unearned gravitas. A key piece of evidence in the film is when Jack Burden, a newspaper reporter recruited into Stark’s inner circle, and the film’s narrator, discovers that his boss is in the pocket of corporate oil interests, a plot point that initially triggers his suspicion.

Long, in fact, did just the opposite: his lobbying for a tax on Standard Oil (modest as the tax was, the oilmen screamed it was socialism) created a windfall that led to the inauguration of a public highway program and the modernization of the state university. Twenty-five years later, Randy Newman, in “Kingfish,” observed Long from his constituents’ perspective:

Who took on the Standard Oil men

And whipped their ass

Just like he promised he’d do?

Ain’t no Standard Oil men gonna run this state

Gonna be run by little folks like me and you

While being characteristically tongue in cheek, Newman captures the past political climate, detailing the threat Long posed to the old social order.

This threat is cranked up to melodramatic heights, as befits a political potboiler. Retaining his upper-class status (regardless of how many times he tries to renounce this status), Burden is complicit in how Stark’s “you’re either with us or against us” ethos wreaks statewide havoc. Stark’s rise to power is catalyzed by his giving the rural poor what they need—healthcare and education—in exchange for their votes. In marked contrast to the borderline fascist tendencies of the lower class, Burden’s friends from the landed gentry are harder to corrupt, because, of course, there’s less that Stark can offer them that they don’t already have.

Visually the film distinguishes between the fire of the torchlight rallies for Stark, staged to resemble those in Nazi Germany, and the water of the bay that cordons off Burden’s upper-class enclave—the last refuge for the democratic principles besieged by Stark’s political machine. When an uneasy truce is brokered, the honorable Judge Stanton, whose family and the Burdens have long been tight, agreeing to be Attorney General, it’s the calm before the storm.

At this juncture, it’s well worth noting that the film paints a rather curious picture of democracy, one that disenfranchises everyone except the upper class. This move has its roots in the creation of the Constitution. Southern leaders demanded that slaves count in a state’s population for calculating seats in the House of Representatives. A compromise was reached: each slave counted as 3/5 of a person. This logic has always been behind voter suppression tactics—only the right people should be allowed to vote (Hi Mitch, glad to see you again!)

The film then shifts into the mode of a heroic tragedy, starring Stanton. One of Stark’s cronies is caught with his hand in the till. Stark’s attempt at a cover-up angers Stanton, who resigns and immediately goes over to the side of those launching impeachment proceedings against Stark. In retaliation, Stark orders Burden to dig up dirt on Stanton.

Reluctantly Burden goes about his research, and, surely enough, discovers that Stanton, in the past, participated in a shady deal. Burden confides, in private, to Stanton’s son, who is his best friend, and daughter, who is his love interest. In a profound betrayal, the daughter informs Stark (she is his mistress)—just in case you didn’t think the film was also blatantly sexist.

Stark confronts Stanton. He falls on his sword; behind closed doors, he blows his brains out. The stage is set for a revenge straight out of Greek tragedy. In a restaging of Long’s assassination, Stanton’s son shoots Stark. His last words:

Stark confronts Stanton. He falls on his sword; behind closed doors, he blows his brains out. The stage is set for a revenge straight out of Greek tragedy. In a restaging of Long’s assassination, Stanton’s son shoots Stark. His last words:

It could have been the whole world, Willie Stark. The whole world…Willie Stark. Why did he do it to me… Willie Stark? Why?

Sic semper tyrannis*, I guess.

Having been canonized as a classic by having won Best Picture, All the King’s Men does the cultural work of legitimizing the Southern aristocracy’s rewriting of history. It’s aestheticizing of political rhetoric in this manner traces back to The Birth of a Nation (1915).

*”Thus always to tyrants” Variant: “Ever thus to deadbeats, Lebowski” (in The Big Lebowski)