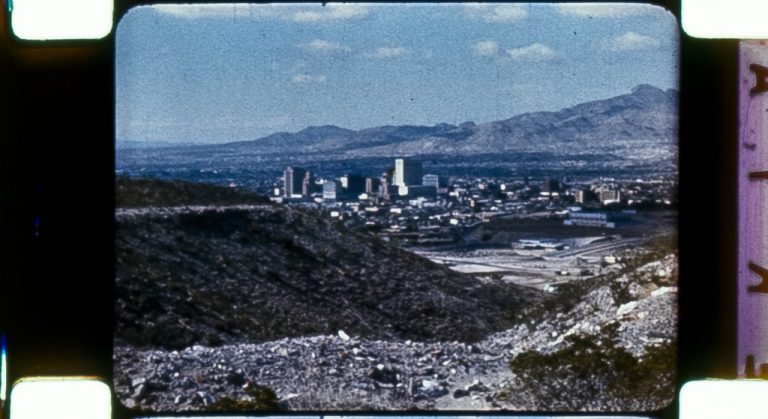

The story behind Manos: The Hands of Fate is almost as legendary and unintentionally fascinating as the movie itself. A part-time actor and full-time fertilizer salesman named Hal P. Warren runs into Hollywood screenwriter Sterling Silliphant (whose In the Heat of the Night would premiere just one year after Manos) in El Paso, Texas. The salesman doesn’t think Silliphant’s business is so hard, and he makes a bet that he can produce a film of his own. His acting experience is on display in Manos as the father, Mike – but it shows way more of his experience in shoveling a whole load of fertilizer.

As a result, Manos has developed a reputation as one of the best bad movies of all time. Despite that, it can be a tough watch. Certainly, the subject matter, including sexual harassment, sexual slavery, and child abuse makes it hard to point and laugh along. Even the fast-talking wisecrackers of Mystery Science Theater 3000 can only groan in disgusted horror when the ending reveals little Debbie has become one of the Master’s wives – and their Rifftrax commentary shows they still couldn’t come up with anything funny about it twenty years later. Then, again it was hard for me not to bust up watching the cut to creepy old Torgo’s face peeking in the window as the heroine undresses.

A lot of the same things that make it fascinating when you first put it on can wear on you by the time you get to the end. The production was so shoestring that Manos has literally no editing, which goes a long way to explain the bizarre shots of actors apparently making faces at the camera as they try to figure out whether it’s rolling or not. We should probably be grateful Warren’s primitive equipment shut down every 32 seconds. The Videohound Golden Movie Retriever describes its lowest rating, the “WOOF!” as “Watching your neighbors’ vacation videos might be less painful,” and a good chunk of Manos is literally that, with long, long shots of the Texas freeway from the car. Or, as Mike Nelson put it on the Rifftrax commentary, “Oh look, vacation footage from my trip to hell!”

And that’s appropriate, because there is something genuinely unsettling here unrelated to any of the movie’s attempts at horror. There’s a weird dream geography to the “big place” where the Master and his wives slumber, which doesn’t seem to exist anywhere in directional space relative to the house where most of the movie takes place. The amateurish nighttime photography has a gritty, creepy atmosphere that you can see David Lynch emulating (purposely?) in his experiments with flashlight-lit night shots. Not that Manos is consistent – the famous “it will be dark soon” scene could not have been filmed on a sunnier day! The consumer-grade equipment occasionally gives Manos the feel of a prehistoric found-footage horror movie.

The plot, such as it is, involves a stereotypical middle-class family on their “first vacation,” who get some bad directions that send them off into the desert. They stop at a rundown old shack for directions, and find Torgo, a strange little man with inexplicably enormous kneecaps. Allegedly he was supposed to be a satyr, but he put on the goat-leg rig backwards. That’d also explain his bleating voice tHaT fAnS lIkE tO iMiTaTe LiKe sO. Whatever those kneecaps were supposed to be for, they clearly weren’t easy to get around in, as Torgo awkwardly stumbles around like he’s trying either to get his groove on or just not fall flat on his face. His substance intake can’t have helped: pretty much the whole cast and crew agree his actor, John Reynolds, was an avid drug and liquor enthusiast, and he’s obviously sloshed out of his mind in most of his close-ups.

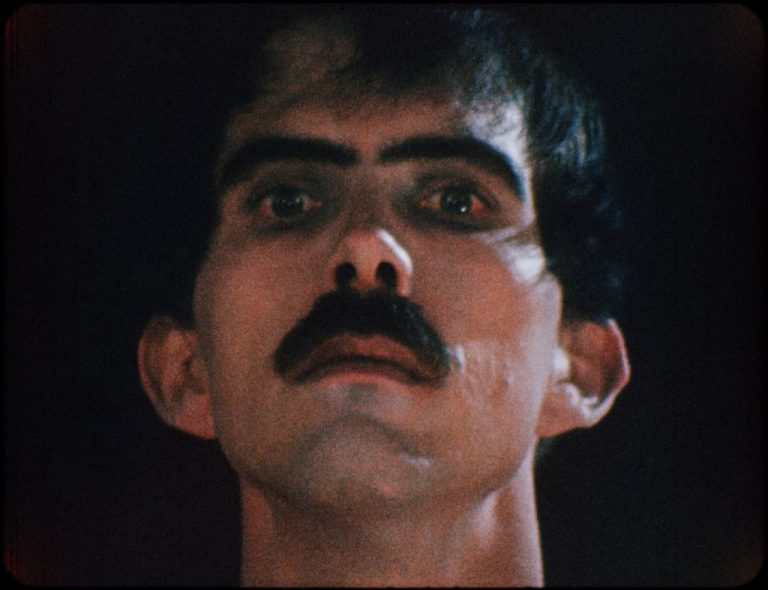

He warns them that “the ma-aster would not appro-ove,” and he’s right: the Master is a sinister devil-worshipper whose gaunt, mustached face sometimes looks creepy, but other times looks like jolly old Ned Flanders.

The strange little man who warns the heroes of impending doom is a boilerplate horror character. But Manos, completely by accident, takes it in a strange new direction. Mike doesn’t just ignore his warning. He straight-up demands that Torgo let them stay in his hideous shack.

The strange little man who warns the heroes of impending doom is a boilerplate horror character. But Manos, completely by accident, takes it in a strange new direction. Mike doesn’t just ignore his warning. He straight-up demands that Torgo let them stay in his hideous shack.

He’s another stock character: the disbelieving husband who pooh-poohs his wife’s suggestions that anything horrible might be going on. But Warren puts his own spin on this stereotype too – by ratcheting it all the way up to “gaslighting asshole.” Even before they get to the house, he insists they’re going the right direction as he drives through the middle of a post-apocalyptic wasteland, because, “I’ve never gotten us lost before,” even though it’s his “first vacation.” And once things do start getting weird, he ignores them all. Having to sleep in a nasty old shack? It’ll be fine! Creepy portrait of some guy who Torgo insists is dead but “always with us”? “You’re probably just imagining things!” Dog gets murdered? Probably just a wild animal! Wife gets molested by the creepy housekeeper? Alright, I guess we can leave if you’re gonna make such a fuss about it. See a horrible satanic sex cult with your own two eyes? Well, now, panicking won’t get us anywhere! When Joel and the bots imagine him comforting his grieving daughter with the kind words, “You never had a dog!” it’s not much of an exaggeration.

People like to say that learning any skill involves learning what not to do. If that’s the case, Manos is practically a film school all by itself. If you want to be generous, and plenty of people do, you can say it’s a work of outsider art with a filmmaking style that’s not so much bad as outside the rules of the bourgeois Hollywood establishment. But whether or not every filmmaking choice is wrong, they’re just all so weird.

The writing is wrong – the redundant repetitiveness of the line, “There is no way out of here. It will be dark soon. There is no way out of here,” is legendary, but that’s not just Torgo’s weird speech patterns – everyone talks like that, as if Warren ran out of ideas for lines and just recycled them to fill up the script. Even Mike, our beacon of normalcy, pulls it out a couple times, and one of the wives somehow manages to repeat and contradict herself at the same time: “The woman is all we want! The others must die! They all must die! We do not even want the woman!” Or how about this surreal little one-act play near the end?

“Vacations are fine, but this one should be great!”

“Yeah the whole gang’s coming up for the weekend what a blast!”

“Hmm.”

The action is wrong – Warren’s attempt to give us a horrifying chase scene mostly involves the characters inexplicably falling over, and over, and over again. And then Mike has the bright idea to go back and hide at the house, which if you’ve been paying attention (and even if you haven’t!) is the exact place they’re running from. And then there’s that bizarre shot of the wives attacking Torgo, which gave Manos’ only contemporary review its hilarious headline: “Hero [sic] Massaged to Death in ‘Manos – T he [sic] Hands of Fate!’”

The dubbing is wrong– Hal Warren’s primitive equipment couldn’t record sound, so he had to loop it after the fact, and only a fraction of the cast could make it. Little Debbie is dubbed by a middle-aged woman doing some kind of voice that sounds nothing like any human child, and that’s when it’s intelligible at all. The child actress allegedly burst into tears when she heard what Warren had done to her voice! At one point, Warren dubs a conversation between Mike and a state trooper all by himself without varying his inflection even one little bit. With their backs to the camera, we can’t see either character’s lips move, and we have no choice but to conclude Mike’s talking to himself!

The filming is wrong – when critics are looking to damn with faint praise, they often say, “At least the actors are in focus,” but Manos can’t even get that much right. Even in a climactic shot of the Master descending on the hapless family, the focus is squarely on the wall behind him! As eerie as the nighttime photography can be, it creates its own set of problems. Stunt coordinator Bernie Rosenblum (one half of the teenage couple who we keep cutting back to for no apparent reason) prided himself on his most impressive trick as he played Mike tumbling off a cliff – until he found out the scene was so dark he was invisible! And if you look closely, you can see that the cameras and lights attracted swarms of moths.

The editing is wrong – we already talked about how little of it there was, but one smash cut, from the Master raising his wives to him sitting on the bench with a look of hilarious irritation on his face as they all shout over each other at once, is so bizarre it’s hard to believe it wasn’t an intentional joke.

The music is wrong – Manos is occasionally soundtracked by an extremely tone-deaf diva performing some kind of torch song with relevance known only to her. Other times, there’s a jazzy flute that seems just as off-key, even if it’s hard to tell how much of that is because of the cruddy, degraded sound quality. And, of course, there’s the “haunting Torgo theme,” which sounds more appropriate for a circus clown – which might actually fit pretty well, come to think of it. The first time I saw the clip of him carrying the bags on YouTube, I couldn’t stop laughing, especially when it abruptly stops and just as abruptly starts back up again.

Even the title is wrong. If you took even one Spanish class, you probably know it translates to Hands: The Hands of Fate. But the real question is, what made Warren think he could get away with it in the majority-Hispanic city of El Paso? And, like everything else in this weird, weird little film, what made him think it was a good idea to begin with?