It took me as long to acquire inhibitions as others (they say) have taken to get rid of them. That is why I often find myself at such cross-purposes with the modern world: I have been a converted Pagan living among apostate Puritans.

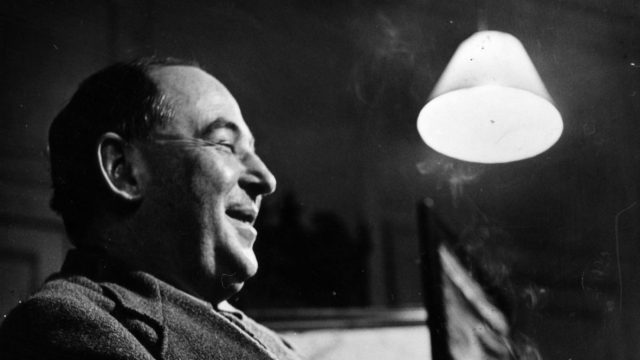

I don’t know if any other writer has influenced me as much as C.S. Lewis. I picked up Surprised by Joy years since the last time I’ve read one of his books, and I still find his voice everywhere in my work: the rhetorical flourishes, the integration of quotations into sentences, the total disinterest in the belief that you can’t open a sentence with a conjunction (he’s the only other writer I can think of to open a sentence with “neither”), lists just like this one. While he has been adequately, maybe even over-recognized, for his impact on modern Christianity, he never seems to have taken his place alongside the great secular writers of the century — I underlined more passages in this book than I have for any other writer besides Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

My copy of Surprised by Joy tags it as “Religion/Autobiography,” but it’s pretty far from the usual, events-based form of the genre. Much of it takes place inside the author’s mind: the climax takes place while he’s sitting still on top of a bus. Most of the major supporting characters are long-dead authors. And not because the young Lewis’ life was uneventful: in between his “life of the mind,” there’s hints of life in the trenches of World War I that he brushes off as “even, in a way, unimportant.” Even at the time, he recalls looking at his life with detached intellectualism: “This is War. This is what Homer wrote about.” A few pages later, he writes that the primary impact of the war was in helping him understand the philosophical ideas of Emmanuel Kant and the reading he did in the hospital. And he doesn’t focus on his solitary moments for lack of company either: he briefly describes a number of great friendships, one of them, with Arthur, among the vividest I’ve ever read. But his primary interest is in what they taught him — even J.R.R. Tolkien, one of the most famous literary partnerships not to involve Parisian cafés, gets a single sentence (and that sentence is less about him than how he overcame Lewis’ prejudices against Catholicism and philology). So, is this a self-centered, navel-gazing text along the lines of other, lesser memoirs? Not really — while he valued solitude, Lewis’s philosophy doesn’t have much room for self-regard. His approach becomes clearer when he describes his life studying with Professor Kirk (published the same year as his origin story for another Professor Kirk in The Magician’s Nephew): it was “selfish, but not self-centered: for in such a life my mind would be directed toward a thousand things, not one of which is myself.” Or, when, in the Preface, he’s asked to explicitly outline his intentions, showing his classicist discomfort for modernist self-contemplation: “The story is, I fear, suffocatingly subjective; the kind of thing I have never written before and shall probably never write again” and “The book aims at telling the story of my conversion and is not a general autobiography, still less a ‘Confessions’ like those of St. Augustine or Rousseau. This means in practice that it gets less like an autobiography as it goes on.”

It certainly starts out a lot like an autobiography, an extremely dry and statistical one: “I was born in the winter of 1898 at Belfast, the son of a solicitor and a clergyman’s daughter. My parents had only two children, both sons, and I was the younger by about three years.” Mercifully, it picks up from there, colorfully describing the character he inherited from both his mother’s and father’s side. (He doesn’t remark on the fact that a man so synonymous with Britishness actually grew up in Ireland, but there you are.) Then he introduces his definition of Joy, and it only gets better from there. While the word suggests fulfillment of desire, here it describes a painfully, beautifully unfulfilled one — and discovering what the desire is for becomes the central thread of the conversion narrative. (And even if he denies any similarity to Augustine’s Confessions, he’s still following along with that book’s most-quoted passage and statement of intent: “Our hearts are restless until they find their rest in Thee.”) “I am only a reminder,” Joy says, personified, near the end. “Look, look! What do I remind you of?”

It’s an old cliché that any work with a first-person narrator exists in two timelines: the timeline of the events being described, and the timeline they’re being recalled from. Part of the fun of this book, though, are the ways Lewis makes that literal, especially here in the first chapter when he twice yanks us out of his memory to the exact moment of his writing the words we’re currently reading: he wonders why his mother would have bought him a pop-up book with a movable stag beetle that traumatized him throughout his childhood “unless, indeed (for now a doubt assails me) unless that picture is itself a product of my nightmare” and a few pages later “Where all these books had been before I came to the New House is a problem that never occurred to me until I began writing this paragraph. I have no idea of the answer.” It doesn’t often get that literal again, but you can still see Lewis regarding himself from a comfortable distance — there’s a rich vein of self-deprecation here. If you were to compare most author’s memoirs with their fiction, you’d probably see them in their heroes. But the chubby, “priggish,” determinedly rationalist young Lewis most resembles Narnia’s “young boy named Eustace Scrubb, and he almost deserved it.” In fact, Lewis’ metaphor for his conversion is almost recycled from Eustace painfully shedding his skin to be restored to human form after becoming a dragon: “I unbuckled my armor, and the snowman started to melt.”

Speaking of Narnia, Lewis’s account of his childhood includes a kind of embryonic version, first called Animal-Land and then, merging with his brother’s imaginary playland of a fictionalized India (insert commentary on colonialism here) Boxen. Then again, the connection may be more tenuous than it appears. Lewis himself sees them as two very different animals (heh): “It was almost astonishingly prosaic…Animal-Land had nothing whatever in common with Narnia except the anthropomorphic beasts. Animal-Land, by its whole quality, excluded the least hint of wonder.” That said, it’s hard not to see an echo of Lewis’s childhood pseudo-history of armored animals in Narnia’s Reepicheep, or the maddeningly allusive timeline (who was Camillo the Hare?) in some editions of the series. His recollections are among the highlights, and when he says “And now that I have opened the gate, all the Boxonians, like the ghosts in Homer, come clamouring for mention. But they must be denied it. Readers who have built a world would rather tell of their own than hear of mine; those who have not would perhaps be bewildered and repelled,” my response has always been “No! Keep going!” The Lewis estate seems to have felt the same way: they published the surviving notes as Boxen: The Imaginary World of the Young C. S. Lewis in 1985.

One of the Boxonians, Lord Big, serves as a mirror of Surprised by Joy’s most memorable character, Lewis’s big, blustering Irishman of a father. As a lawyer, the elder Lewis had developed a great talent for oratory that fit comically poory into the context of fatherhood. See, for instance, the moment when young Lewis comes to see his father as a clown rather than an authority figure, after the old man had caught him and his brother dismantling a ladder to build a tent:

“Then the lightnings flashed and the thunder roared; and all would have gone now as it had gone on a dozen previous occasions, but for the climax–‘Instead of which I find you have cut up the step-ladder. And what for, forsooth? To make a thing like an abortive Punch-and-Judy show.’ At that moment we both hid our faces; not, alas, to cry.”

In addition, he had a great talent for “reading between the lines” to find complex meanings in simple things: always completely wrong, of course, and always completely unshakable.

“One conversation, held several years later, may be recorded as a specimen of these continual cross-purposes. My brother had been speaking of a re-union dinner for the officers of the Nth Division which he had lately attended. “I suppose your friend Collins was there,” said my father.

- Collins? Oh no. He wasn’t in the Nth, you know.

- (After a pause.) Did these fellows not like Collins then?

- I don’t quite understand. What fellows?

- The Johnnies that got up the dinner.

- Oh no, not at all. It was nothing to do with liking or not liking. You see, it was a purely Divisional affair. There’d be no question of asking anyone who hadn’t been in the Nth.

- (After a long pause.) Hm! Well, I’m sure poor Collins was very much hurt.

There are situations in which the very genius of Filial Piety would find it difficult not to let some sign of impatience escape him.”

The record of Lewis’ life as a reader as he approaches adulthood is especially interesting from six decades’ distance. The basic outlines will seem familiar to anyone familiar with the Nerd Narrative: a lonely, introverted youth throws himself into stories of heroic fantasy. But instead of comic books and Hollywood blockbusters, Lewis finds his solace in the great classics: Homer, Wagner, William Morris. Of course, that’s not the whole story – he also gives credit to Beatrix Potter, H. Rider Haggard, H.G. Wells, and the book that he says “baptized his imagination,” George MacDonald’s Phantastes, is what we would now call “genre fiction.” I’m not trying to enforce the “high culture/low culture” divide here — have you seen what I normally write about? — and even Lewis himself acknowledges that taking pride in his highbrow tastes led him to insufferable “priggery.” (And, to be fair, he still hadn’t quite outgrown it at this point – the book is an intimidating web of literary allusions, often without context or even translation). Still, if you’re going to be a prig, you can at least earn it — the modern nerd priding himself on his superior knowledge of Star Wars and Adult Swim is far more insufferable than the young Lewis could ever hope to be.

And I wonder if the stabs of Joy he felt from these timeless, mythic texts are accessible to those of us raised on disposable modern entertainment (I know I have a hard time recognizing it). Lewis himself gets at the difference between the mythic and the escapist:

“For many years Joy (as I have defined it) was not only absent but forgotten. My reading was now mainly rubbish; but as there was no library at the school we must not make Oldie responsible for that. I read twaddling school-stories in The Captain. The pleasure here was, in the proper sense, mere wish-fulfilment and fantasy; one enjoyed vicariously the triumphs of the hero. When the boy passes from nursery literature to school-stories he is going down, not up.”

From the text alone, it’s hard to say how much of this is due to culture-wide shift and how much is unique to Lewis – but those allusions suggest his readership had at least some familiarity with Lewis’ own cultural diet, and if it was unusual, he never mentions it.

As he said in the Preface, Lewis’s outer life plays a progressively smaller role in the narrative. His descriptions of the almost surreal cruelty of the British school system are fascinatingly vivid, his narrative of Oxford less so. He still finds plenty of drama in it, though, and Surprised by Joy is essential to anyone interested in his work (it may, in fact, be the best of it). One passage, in particular, serves as the origin for the whole Jungian ethos of his writing: “Word became Flesh, Myth became Fact.”

“Early in 1926 the hardest boiled of all the atheists I ever knew sat in my room on the other side of the fire and remarked that the evidence for the historicity of the Gospels was really surprisingly good. ‘Rum thing,’ he went on. ‘All that stuff of Frazer’s about the Dying God. Rum thing. It almost looks as if it had really happened once.’ To understand the shattering impact of it, you would need to know the man (who has certainly never since shown any interest in Christianity). If he, the cynic of cynics, the toughest of the toughs, were not–as I would still have put it–‘safe,’ where could I turn? Was there then no escape?”

This passage also shows the most refreshing aspect of Lewis’ conversion narrative. We’re so used to a self-centered, results-based view of religion: “You don’t have to believe it, it’s just what works for me,” “From that moment on, my life has been blessed.” Lewis didn’t actually want to find God. “Amiable agnostics will talk cheerfully about ‘man’s search for God’. To me, as I then was, they might as well have talked about the mouse’s search for the cat.” Instead, he finds himself confronted with a solid and even harsh reality. Surprised by Joy isn’t really concerned with what God can do for Lewis, just with what He is. “Long since, through the gods of Asgard, and later through the notion of the Absolute, He had taught me how a thing can be revered not for what it can do to us but for what it is in itself.” Now that so many see faith as oppositional to reality, fighting against the proven science of evolution and revering the least Christian man alive as their political savior, Lewis’ vision is more valuable than ever.