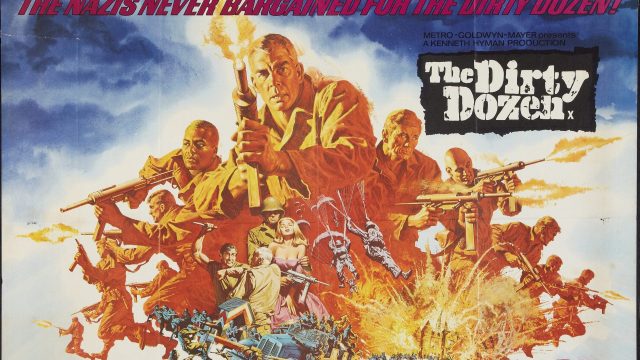

“So that’s it, huh? We’re some kinda dirty dozen?” says absolutely no one in The Dirty Dozen, unfortunately, though someone does get to say the title of the movie. It was impossible for me to watch this classic 1967 World War II film in 2022 without thinking of (The) Suicide Squad, especially since both David Ayer and James Gunn cited the movie as inspirations for their films and James Gunn’s sequel/reboot paid homage in its poster. The comics team actually predates even the original 1965 novel by E.M. Nathanson, having first appeared in the pages of The Brave and the Bold in 1959, but it was John Ostrander in 1987 who created the concept the more recent films are based on, in which Amanda Waller sends supervillains out on suicide missions for the government…a concept that, yes, Ostrander absolutely took from The Dirty Dozen. Robert Aldrich’s film had a good twenty years before it became inextricably associated with DC Comics and almost fifty years before a much-maligned film cemented that pop culture association. Not having read any of the comics but having seen and enjoyed both movies — one a great deal more than the other — I found it fascinating to observe the key differences that made The Dirty Dozen a much more interesting execution of this great premise.

Given that the Suicide Squad comprises comic book supervillains, one naturally assumes them to be killers, and by one I do mean me, as I’m not familiar with every single member of every single iteration so it’s entirely possible there are people in Belle Reve for tax fraud or whatever. Regardless, even if some inmates are on “death row,” on a metatextual level, these characters aren’t in huge danger of being executed because why would a comic kill off a supervillain so banally? On the other hand, a minority of the Dirty Dozen actually face the noose for having killed someone — several of them for sympathetic reasons — so I was surprised to discover that so many of the team members were simply serving decades of hard labor. For the murderers, perhaps getting killed on a mission was preferable to the noose, but that seems like an awfully big risk for the people who aren’t actually facing death for their crimes. Especially when the penalty for failing out of the team is hanging, not just being sent back to prison. What the fuck are these terms? It’s easy to accept the comic book fantasy as just that, but the way it’s originally presented provides real resonance with regards to the prison system and the desperation it puts on the people inside it.

One of the manifestations of this desperation in the Suicide Squad is that each member has a bomb implanted in their neck that Amanda Waller can detonate if they get out of line. This is no empty threat either, as Waller will not hesitate to blow up the head of anyone who attempts to escape. This may seem extreme, and yet somehow it’s less extreme than in the Dirty Dozen, where if anyone escapes, everyone is punished! (With eventual hanging, not immediate explosion.) The film emphasizes the severity of this threat in a scene where Dozen members Jefferson, Wladislaw, and Posey must keep Franko (John Cassavetes) from escaping because hell if they’re going to let him get them all killed. This policy forces each individual to think about the consequences their actions have on the rest of the team, which encourages a camaraderie that doesn’t build naturally when you view your squad as individual flight risks.

Given my experience with the Suicide Squad, I assumed that the members of the Dirty Dozen brought a similar assortment of skills to the team, like having a sword that traps the souls of its victims or being able to climb anything, but…they don’t! They’re just assholes! That’s what they bring to the team. Posey (Clint Walker) may be physically imposing, but no one has an inherent advantage that makes them suited to go on a mission, which means they must undergo rigorous training. I wish we got to see more of the training to see how they became fit for duty, but the film’s uninterested in showing us that part of their development, more concerned with developing their relationships to each other. Instead, when we see them participate in a wargame, we see how far they’ve come. Although they were chosen because of the meanness of their character and their expendability, they do live up to Major John Reisman (Lee Marvin)’s assessment of their capabilities as potential soldiers.

But ultimately what makes the Dirty Dozen so much more interesting is that unlike Waller, Reisman did not choose to lead this team and he actually cares about people. You can see it in his reaction to a hanging in the first scene; he truly believes that giving prisoners an option other than the noose is good for them. He constantly stands up for his soldiers against his superiors, and even when it seems like he’s being kind of a dick — refusing to let them shave or bathe with hot water like the rest of the troop — he does it because he understands that by making himself a common enemy, he can mold the ragtag group of prisoners into an actual unit. Most importantly — and very much to my surprise — he actually goes on the mission with them! He puts his own life on the line alongside them, and that makes him a true leader they can believe in. I recently rewatched Army of Darkness, and I’ve seen few other movies that hinged almost entirely on one actor’s performance, but for my money, The Dirty Dozen absolutely does not work without Lee Marvin’s strong, nuanced, gentle, clever, utterly humane performance as Reisman.

I did enjoy Suicide Squad, flawed though it was, and I really liked The Suicide Squad, so watching The Dirty Dozen helped me place these films (and their comic book origins) in the greater conversation. Of course, even The Dirty Dozen owes its “gather a group of disparate individuals for a common goal” conceit to Seven Samurai, but that would be an entirely different essay. For now, I just want to appreciate the malleability of a single idea that can encompass a bunch of assholes blowing up Nazis and a bunch of assholes blowing up a giant alien starfish.