One day on The Dissolve Facebook group, I listed several traits I found appealing in the films of Wong Kar-wai — cinematic portrayals of loneliness and heartbreak; interconnectedness of humanity, with chance encounters and relationships with strangers having profound effects; the loving use of music, be it orchestral or pop; unconventional narrative structure — and asked for films and/or directors I might enjoy. Longtime friend Sean Gallagher recommended the work of Max Ophüls, and so La Ronde got on my radar. Sure enough, the film did do the things I like in the way I like them done! It’s the story of a series of love affairs adapted from a controversial play about a series of love affairs, but Ophüls and Jacques Natanson add a Master of Ceremonies character who ties the stories together and, in my opinion, elevates the source material. Unless it undermines the source material. It all depends on what you want to get out of a story that follows a consecutive, circular chain of lovers in 1900 Vienna.

In the first scene of Arthur Schnitzler’s play, a sex worker propositions a soldier, and that soldier links to a chambermaid, who links to a young gentleman, until we eventually get to a count, who links back to the original sex worker to complete the circle. As originally presented, these encounters are pure happenstance, and it’s simply whimsical chance that you could actually connect these characters via their love affairs so circuitously. In the film, however, the Master of Ceremonies — wonderfully portrayed by Anton Walbrook, a charming, magnetic screen presence — specifically tells the sex worker which soldier to sleep with. She initiates the circle on his behalf, so in this version, the MC orchestrates the whole affair of the affairs. Does he perhaps represent God, the true architect of happenstance? Or the writer, who bears responsibility for the fate of his characters?

In the play, the connections between these people from different stations in life occur on their own, but in the film, the Master of Ceremonies occasionally intervenes to ensure that the circle continues. He propels the Chambermaid two months into the future — a lovely device I wish Ophüls had used more to enhance the dreamlike nature of the proceedings — and then keeps a visitor from interrupting her tryst with the Young Gentleman. It’s an amusing scene, but quite pointed — had the MC not been there, those two would not have been able to do their business, which would be quite a shame because, uh, their flirtatious build-up is one of the sexiest things I’ve seen onscreen that involved no actual sex. Let them bone, please. Later, the MC waits on the Husband and the Young Girl in a restaurant, going so far as to give the husband a pep talk in the middle of his date.

Throughout the film, the Master of Ceremonies sings a very hummable song about his characters turning, turning on the carousel of love, so it’s clear that he treats them as characters in the story we are witnessing, the story he is ensuring occurs. But are they then not reflections of real life, as intended by Schnitzler in his play? Of course, the characters were merely characters in the play as well, but Schnitzler never called attention to it.

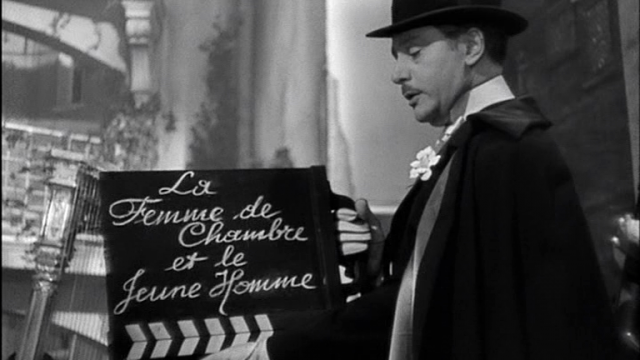

Ophüls crafts a deliberately cinematic adaptation of a theatrical work; the Master of Ceremonies quips that they could be on a film set as, in fact, we see a camera and lighting equipment. Later we even see the orchestra playing the score. In the greatest meta moment of the film, the MC censors a sex scene by literally cutting the film in front of us. All of these touches highlight the artifice of the entire enterprise, so can this reflect the truth of life if it’s so clearly contrived?

This fundamental difference between the film and play allows for some interesting discussions of how we relate to fiction and the distinction between “realism” or “authenticity” and “truth.” I can’t imagine liking the play as much as the film because the Master of the Ceremonies makes the entire movie for me; I love omniscient narrators and find Ophüls’s take on the device delightful. The film opens with the Master of Ceremonies unable to decide whether he is the author, an accomplice, or a passer-by, declaring that he merely represents our desire to know everything, to see from every perspective — he’s the narrative glue that, in the play, we would have to construct ourselves. Wouldn’t it be lovely if we could trust in such narrative glue in reality? Whether it’s a mellifluously voiced Frenchman or cosmic forces beyond our comprehension, it is comforting to think that there is a guiding hand that holds the world together, creating circular narratives, circles that interlock to form a chain of humanity.