Bruno Schulz’s The Street of Crocodiles was originally published in Poland as Cinnamon Shops. While both titles come from chapters (short stories?) within the book, for once, I have to give it to the translators for going against the original text. It’s possible cinnamon still had an air of the exotic in 1933, but Cinnamon Shops leaves readers unprepared for what they’re about to see between these covers. It’s a mundane title, and Schulz’s book is many, many things. Mundane is not one of them.

Then again, that sensation of surprise attack may have been exactly what Schulz had in mind. Street of Crocodiles begins as an apparently ordinary childhood reminiscence of the narrator’s life in the Polish village of Dorobych with his eccentric father. It’s full of strange and vivid metaphors, but there’s no indication we’re supposed to take them literally. But slowly, Schulz lets the strangeness of his vision creep up on you. Wait, did those thistles just shout? Did the birds in the wallpaper just twitter? Surely, Uncle Mark’s face can’t really be slowly turning blank, can it? By the next chapter, where the father begins shrinking as Schulz describes the process in increasingly literal language, there can no longer be any doubt that we’re miles away from the mundane world.

Schulz piles up images like this at a frightening speed, as if he’s been saving up every odd thought he had all his life and crammed them into one book. It’s not unlike the scene in “The Night of the Great Season,” where the narrator’s tailor father refuses to open up his shop until it finally explodes into a whole country of fabric. That chapter alone contains more ideas in its six pages than most whole novels, and it’s not even the highlight of the book.

I discovered The Street of Crocodiles on my aunt’s bookshelf almost a decade ago and picked it up to feed my fascination at the time with everything Eastern European and because I recognized the title from the short film by the Brothers Quay (good luck finding any overlap between the two versions — the Quays give the words “loose adaptation” a whole new meaning). My aunt has never read it and says she has no idea where it came from, which is fitting for this dispatch from another dimension. Mistaking it for a short story collection, which maybe it is and maybe it isn’t, I dove into the middle with the title story, then moved on to “Cockroaches,” where the boy’s father is somehow simultaneously dead, a cockroach, and a stuffed vulture.

Of course, I was hooked. I returned to the beginning and read it through to the end, but I can’t say I really absorbed it — Schulz’s imagination was too fertile for that. It sent my mind racing with ideas for my own stories too fast to comprehend what I was reading. But that put me in the perfect position for this article. I knew I had to write about this book, and yet I got to experience most of it as if I was reading it for the first time. It inspired me to the kind of methodically quixotic process the tailor is always embarking on — I’d highlight sections I wanted to use in this article in blue, sections I wanted to steal for my own fiction in gold, and sections that were simply excellent in themselves in pink.

The arbitrariness of this system should be obvious, and since I read it in the bathtub, it mostly led to my highlighters getting soaked. And that was before I knocked the whole fucking book into the bathtub, washing away most of my notes, which also seems like something that would happen to the luckless father, who accumulates an enormous collection of exotic birds and raises them from eggs like a mother hen until his tyrannical maid shoos them all away. Street of Crocodiles, it would seem, is a dangerous book. It buries itself into your brain until you find connections everywhere.

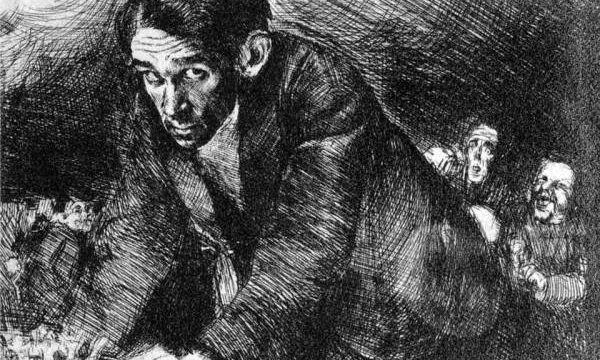

Schulz’s life and career were tragically cut short — only one other collection, The Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass survives. Street of Crocodiles wasn’t even available in the US for forty years. But you can see echoes of his slim surviving work in other artists. His shrinking father is eerily similar to the shrinking mother in One Hundred Years of Solitude. And before Marquez placed a general in his labyrinth or Jorge Luis Borges wove the image through so much of his work, Schulz was equally obsessed with its symbolism. His obsession with mannequins reverberates through the Czech filmmakers Jiri Barta and Jan Svankmajer, and from there to the Quay Brothers.

The Street of Crocodiles isn’t perfect. It shows a nasty misogynist streak as Schulz populates his dreamworld with women with no goals beyond seduction, castration, or both, most prominently with the tyrannical maid Adela who torments her alleged employer. But as many echoes of this book as I’ve found elsewhere, there’s still nothing else quite like it.

The obvious precedent for Schulz is Franz Kafka, and Schulz lent his name to his friend Józefina Szelinska’s translation of The Trial. It’s certainly hard not to think of The Metamorphosis when Schulz turns his protagonist into a cockroach. But while Kafka begins his story after the transformation, Schulz’s approach is more Cronenbergian:

I saw him sometimes looking pensively at his own hands, examining the consistency of skin and nails on which black spots began to appear like the scales of a cockroach.

In daytime he was still able to resist with such strength as remained in him, and fought his obsession, but during the night it took hold of him completely. I once saw him late at night, in the light of a candle set on the floor. He lay on the floor, naked, stained with black totem spots, the lines of his ribs heavily outlined, the fantastic structure of his anatomy visible through the skin; he lay on his face in the obsession of loathing which dragged him into the abyss of its complex paths. He moved with the many-limbed, complicated movements of a strange ritual in which I recognized in horror an imitation of the ceremonial crawl of a cockroach.

The Trial was famously cobbled together from unnumbered chapters after Kafka willed it to a friend with the instructions to burn it — it’s hard not to wonder if something similar happened with Street of Crocodiles since the father appears alive and well and not a cockroach in the next chapter. You see why I can’t be sure whether to call this a novel or a short-story collection.

But Schulz leaves reality even farther behind than Kafka. And here’s another way the book rewired my brain around its contours: reading Street of Crocodiles while preparing the Selected Shorts series, it was hard not to see how many obsessions Schulz shares with the Fleischer Brothers and other animators on the other side of the Atlantic — the mutability of form, the potential for life in dead material, bodies splitting into smaller bodies. Perhaps the animators chose these themes to appeal to children, but Schulz is explicit in his letters that he deliberately tried to recapture the mythological world of childhood and explore it through adult eyes, with all the darkness that implies. Whatever the method, just tell me you can’t imagine this scene from “The Gale” set to jaunty swing music in a Hollywood cartoon. (Actually, you don’t have to: Just look at this scene from Disney’s Lullaby Land the same year.)

The regiments of saucepans and bottles and bottles rose under the empty roofs and marched in a great bulging mass against the city…

Then the black rivers of tubs and watercans overflowed and swept through the night. Their black, shining, noisy concourse besieged the city. In the darkness, the mob of receptacles swarmed and pressed forward like an army of talkative fishes, a boundless invasion of garrulous pails and voluble buckets.

Drumming on their sides, the barrels, buckets, and watercans rose in stacks, the earthenware jars gadded about, the old bowlers and opera hats climbed one on top of another, growing toward the sky in pillars only to collapse at last.

And all the while their wooden tongues rattled clumsily, while they ground out curses from their wooden mouths, and spread blasphemies of mud over the whole area of the night, until at last these blasphemies achieved their object.

Well, the Hays Office may have objected to that last bit, but you get the idea.

Schulz writes a kind of manifesto on these obsessions in the book’s centerpiece, “Treatise on Tailor’s Dummies or The Second Book of Genesis.” It’s hard to know how seriously to take it — the whole passage comes from the mouth of the tailor, who’s not all there at the best of times, and who Schulz describes as a “heresiarch.” He tells the girls in his shop that there’s no such thing as an inanimate object: “In the depth of matter, indistinct smiles are shaped, tensions build up, attempts at forms appear. The whole of matter pulsates with infinite possibilities that send dull shivers through it. Waiting for the life-giving breath of the spirit, it is constantly in motion.”

Schulz takes this idea to much more disturbing places than his cartoon contemporaries. Long before the term “uncanny valley,” the concept of the uncanny, the eeriness of artificial representations of human forms, was essential to both psychoanalysis and Surrealism. But neither Freud nor Dalí brought up that terror as vividly as Schulz:

Figures in a waxwork museum, even fairground parodies of dummies, must not be treated lightly. Matter never makes jokes: it is always full of the tragically serious. Who dares to think that you can play with matter, that you can shape it for a joke, that the joke will not be built in, that it will not shape it like fate, like destiny? Can you imagine the pain, the dull imprisoned suffering, built into that dummy which does not know why it must be what it is, why it must remain in that forcibly imposed form which is no more than a parody? Do you understand the power of form, of expression, of pretense, the arbitrary tyranny imposed on a helpless block, and ruling it like its own tyrannical, despotic soul? You give a head of canvas and oakum an expression of anger and leave it with it, with the convulsion, the tension enclosed once and for all, a blind fury for which there is no outlet. …

Have you ever heard at night the terrible howling of these wax figures, shut in their fair booths; the pitiful chorus of those forms of wood or porcelain, banging their fists against the walls of their prisons?

Human forms aren’t the only ones with the potential for life. Elsewhere, bolts of cloth reproduce and expand, and garbage heaps grow into metal vines and bushes.

Earlier, the tailor verbalizes another of Schulz’s guiding obsessions as he plots the creation of his own race, not quite of atomic supermen, but mannequins: “The Demiurge was in love with consummate, superb, and complicated materials; we shall give priority to trash. We are simply entranced by the cheapness, shabbiness, and inferiority of material.” In other words, he loves trash, anything dirty or dingy or dusty, anything ragged or rotten or rusty, and Schulz shares that love.

The title story explores a district so disreputable it’s a blank on the map of the city, a “parasitical quarter,” “a pseudo-Americanism grafted on the old, crumbling core of the city, shot up here in rich but empty and colorless vegetation of pretentious vulgarity” full of “cheap jerry-built houses with grotesque facades.” Schulz explicitly compares that colorlessness to a cheap catalog come to life, a “paper imitation” of the modern city, “a montage of illustrations cut out from last year’s newspapers,” where even the sky is “shoddy.”

As disgustedly as his fascination manifests itself in this story, Schulz joyously glories in trash elsewhere. In “Cinnamon Shops,” street performers are endowed with all the dignity of high opera. In “The Night of the Great Season,” he lovingly describes “kiosks and barrows, made from empty boxes, papered with advertisements, full of soap, of gay trash, of gilded nothings.”

If Surrealism was already well established by the time Schulz joined the fray, he got out well ahead of Pop Art. At the climax of that story the father’s lost birds come to his rescue as the crowd demanding he open his shop turns into a mob, but as they come closer they’re revealed as a “brood of freaks,” a “malformed, wasted tribe of birds…returning degenerated and stupidly overgrown. Nonsensically large, stupidly developed, the birds were empty and lifeless inside…nothing but enormous bunches of feathers tufted with carrion.”

If matter can be shaped, it can be reshaped, and it is. Besides the many indignities the tailor’s body suffers, in his treatise, he describes his brother, who was transformed into a rubber hose. The narrator’s Aunt Perasia turns so livid when Adela the maid throws her rooster into the fireplace, “it seemed in her paroxysm of fury she might disintegrate into separate gestures, that she would divide into a hundred spiders, would spread out over the floor in a black, shimmering net of crazy running cockroaches. Instead, she began to shrink and dwindle…black and folded like a wilted, charred sheet of paper, oxidized into a petal of ash, disintegrating into dust and nothingness.”

I love reading works from other languages, not just for the obvious diversity of perspective they can offer, but for how they can make me see my own language in a new light. It takes a good translator to do that, and Celina Wieniewska is a great one, refusing to hammer the square peg of Schulz’s poetic Polish into the round hole of idiomatic English. What native speaker would ever think to describe their narrator lying “among the remains of breakfast” or his professor as “given to esoteric smiles and discreet silences,” or the “cosmic homelessness and loneliness of the wind?”

Schulz’s debut should have been the beginning of a body of work that changed the literary landscape forever. Instead, the Holocaust, that gaping hole in the middle of 20th-century history, swallowed him up in his prime. The Jewish author’s artistic skills saved his life for a time when Felix Landau of the SS hired him to create a mural for his children’s bedroom. That might tempt us to brand him a collaborator, but he used the time well to collect stories from survivors for his magnum opus, The Messiah, which he smuggled out of the country with Gentile friends. Chronicling such harsh realities may seem like a strange left turn for Schulz, but the enormousness of that enormity has always rendered it incomprehensible — maybe surrealism was the only way to make it real.

I’ve written about the allure of the lost masterpiece before, and they don’t get any more lost than The Messiah. We know the manuscript exists. But no one knows where. Also lost: the countless future masterpieces Schulz might have created if he had lived.

Instead, he died senselessly in an incident that reminds us why Hannah Arendt had the Holocaust in mind when she invented the phrase “banality of evil.” Landau murdered a Jewish prisoner favored by his colleague Karl Günther, who responded by shooting Schulz dead in the streets. “You killed my Jew,” Günther said, simply, “so I killed yours.” Schulz, the author who reached into the alternate brainspace of childhood to create works of unprecedented magic, killed by childish pettiness in its ugliest form. We have so little left of him, but what we do only underscores what a gigantic tragedy his murder is.