Becoming a celebrity usually requires a unique personality or an exceptional action. Hollywood magnified the popularity of theatrical performers, with each star sporting a uniquely charismatic attraction for the viewer, embodying what Elinor Glynn called the “it” factor. King Vidor’s Show People displayed this modern concept of success, showing Peggy Pepper (Marion Davies) becoming a “natural” comedienne by abandoning the pretenses of studied technique and letting her natural reactions to absurd situations shine through on camera. From early on, the movies validated a new meritocracy that measured success by the degree to which the individual gained positive attention from their inherent attractiveness.

The movie camera enabled this new ethos by placing the personality of the performer at the center of the medium. Motion picture photography, as Walter Benjamin pointed out, possessed the quality of objective observation, whereas painting or sculpture imposed a degree of subjective manipulation by the artist upon the object being represented. Movie magazines and the studios routinely downplayed the artistic license taken by the cinematographer with regards to lighting and makeup in order to accentuate the magnetism of the actor. The emergence of the celebrity as a factor in modern life coincided with the ability of technology to record contemporary events and preserve them for history.

Woody Allen’s mockumentary Zelig spoofs the relationship between fame and the rise of movie culture by cleverly inverting expectations concerning the naturalness of personality and the objectivity of photography. Leonard Zelig, the film’s hero, suffers from a neurological condition in which he instinctively impersonates, both physically and linguistically, the social background of anybody he encounters. His neurosis is so extreme that it becomes a source of public fascination, inspiring songs, dance crazes, and even a biopic. Allen inserts Zelig into pre-existing newsreels and contemporary reenactments aged to look like archival footage. In spoofing the idealization of individual accomplishment through the schleppy misadventures of Zelig’s celebrityhood, Allen uncovers another facet of the movies that would preoccupy another region of film history: one where diversity within the human community would become the focus.

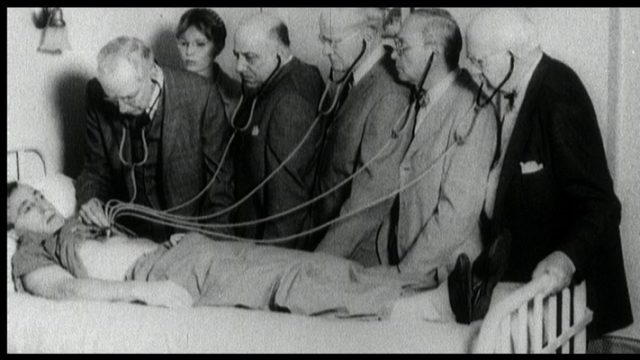

Zelig is first discovered by a diarist friend of F. Scott Fitzgerald at a party in Long Island, where he is seen speaking favorably of Republican economic policies in the dining room in a refined Northeastern accent, only to be spotted later in the kitchen discussing Marxism with the help in a more guttural, working-class dialect. As the off-camera narrator notes, this human chameleon then begins making unexpected appearances in the newsreels and newspapers, batting alongside Babe Ruth for the New York Yankees or playing the trumpet as a Negro in a Harlem dance band. A fracas with the police lands Zelig in the custody of a psychiatric hospital, whose staff, in a twist reminiscent of The Elephant Man, conduct numerous experiments before the cameras to demonstrate his uncontrolled shape- and culture-shifting abilities. Against his will, Zelig attracts the attention of movie stars, musicians, and, of course, French intellectuals, who, upon observing him transform into an orthodox Jew in the presence of two rabbis, proclaim that he ought to be sent to Devil’s Island.

The peculiar nature of Zelig’s notoriety subtly undermines the notion of celebrity by which fame in the 1920s was established. He never reverts back to an authentic, original personality once the cavalcade of motley individuals placed in his presence leave his view. His fame only rests in unconscious ability to impersonate a cross section of humanity. The origins of his identity, and the forces that shaped his predicament, are a mystery to his contemporaries. Zelig demonstrates that assimilation can serve as a font for endless verisimilitude, but the core of his authentic selfhood eludes the camera. Zelig may be as famous as Mary Pickford or Douglas Fairbanks, but there is no synthesis of his public persona and a private identity, because the latter is so completely concealed by his subconscious mastery of cultural appropriation.

The Chaconian theatrics of the hospital doctors is soon challenged, however, by Dr. Eudora Nesbitt Fletcher (Mia Farrow), a Freudian psychotherapist who seeks to re-awaken Zelig’s long-repressed identity, warped, she assumes, by childhood trauma. After struggling to push Zelig past impersonating a fellow psychiatrist, she starts pretending to consult him as her own analyst. The cognitive dissonance caused by flipping the patient/analyst relationship causes the subject to lose control of his façade, and slowly he begins reconnecting to his authentic self, assuming the path to a normal life. The monetary value of Zelig’s celebrity status, however, brings nefarious relatives to the fore. When they break off the therapy, Zelig’s life goes into a tailspin, ultimately sending him off unsupervised into the turmoil of 1930s Europe. Nazis become involved, an aerial escape ensues, and eventually therapist and patient are reunited. Later, under the canopy of holy matrimony, they bone.

In presenting Zelig’s story, Allen foregoes the farcical structure of his traditional films, utilizing tropes of the historical documentary to present the details of his character’s tumultuous life. He skillfully edits archival clips from newsreels, incorporates music from the time period, and inserts talking heads of prominent contemporary intellectuals like Pete Hamill and Susan Sontag to provide color commentary. Although the film includes theatrical recreations to represent a specific period, it does so in a way in which the scratches and decomposition of the film stock matches the older footage. One cannot really distinguish when Allen’s image is transposed over archival celluloid or performed on a sound stage. Since the viewer can easily use their common sense to decode the playful bending of the historical record, the audience recognizes the film as an amusing satire not only of American history but of the documentary form itself.

In presenting Zelig’s chronicle in this manner, Allen interrogates the naïve assumption that the camera is the ultimate arbiter of objective observation. Every utterance by the voiceover interlocutor and the “experts” is clearly a cleverly executed hoax. The director wisely has his narrator and interview subjects deliver the jokes in a straight, deadpan manner, accentuating the absurdity of the events depicted on screen. For the most part, Allen portrays Zelig with minimal use of broad physical comedy, just having the protagonist casually show up at incongruous meetings with famous people. This makes the occasional deployment of slapstick, such as a fracas onstage with Hitler, all the more shocking, because it appears so seamlessly connected to the original visual record.

While managing to be simultaneously humorous and dazzling, Zelig might also be Allen’s most bracing statement on the heterogeneity of American culture. Throughout his career, the director has been criticized for promoting an elitist perspective by relentlessly interpreting Manhattan’s urbanity through the limited lens of its most privileged classes. The world of this film, however, expands to include, among other things, high and low culture, sports and fine art, opera and jazz—in other words, the gamut of peoples and tastes that came together in the U.S. in the first half of the twentieth century. Leonard Zelig, through no design of his own, absorbs and projects the polyphony of the urban landscape without prejudice or malice. His celebrity rests in sublimating his ego to, as Walt Whitman would say, contain multitudes. As his fame reaches its zenith, he literally becomes an “everyman” comprised of all populations in the American spectrum.

Unfortunately, the conventionality of the romantic comedy formula that comprises the film’s back half evades exploring of the full implication of this theme, while the faux documentary format diminishes the dramatic potential in recovering the protagonist’s ego. Radio Days would, in many ways, solve this problem, weaving the intimacy and tensions of family dynamics amidst the fantasies and urban folklore of early broadcasting. The stretch of five features beginning with Zelig and concluding with the latter movie constituted the warmest, most generous, and technically innovative period of Allen’s long career. Four of these (the exception being Hannah and her Sisters) would also present some of the most nostalgic yet bittersweet meditations on the fantasias of celebrity and show business produced in American cinema.