In 1962 many viewers thought that Westerns, and the Hollywood studios, were in decline. The major film making conglomerates had long divested interests in their theaters and cut back in-house production, becoming, in effect, mere distributors. While this transition once increased the number of Westerns released in the late forties and fifties by allowing studios to compete in rural markets, the transition of production to television by 1960 resulted in an influx of derivative product. FCC chairman Newton Minnow specifically cited Westerns as evidence of television’s mediocrity in his famous “vast wasteland” speech.

Moreover, in an era when the sensational designs of thrillers like Psycho drove the emerging youth market, Westerns seemed old-fashioned. Its stars and directors were nearing retirement unless, as in the case of Gary Cooper and Errol Flynn, they were already dead. Newer talent, such as Audie Murphy, failed to break the A list, and those who gained popularity on TV made more money shooting Westerns in Spain and Italy for foreign audiences. The most popular Westerns of 1962 reflected the genre’s state of ennui. Several were resigned to bittersweet or nostalgic acceptance of the genre’s passing, while others pushed this elegiac tone in a more forward-thinking direction.

One way that studios revived interest in Westerns was to go big; mounting lavish productions and top-loading them with big name stars. The Cinerama Corporation’s How the West Was Won exemplified this strategy. It was cast with some of the era’s most popular actors, like Debbie Reynolds, James Stewart, John Wayne, Gregory Peck, and Richard Widmark. Like epics such as Giant, Cimarron and The Wonderful Country, it coupled frontier lore to a family chronicle. It was uniquely episodic, covering the stages of fur trading, wagon trains, riverboats, the Civil War, and the Railroad in the development of American Western history. Each chapter emphasized elements of adventure. It was resplendent with incidents involving Indian attacks, whitewater rapids, and railroad sabotage, and rendered in an eye-stretching process that synchronized three 35mm filmstrips. Although it was the most popular Western of its year, it did not sustain a longstanding critical reputation. Its nostalgia for the romance of a bygone era avoided acknowledging the crisis that the genre faced.

John Ford’s penultimate Western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, directly confronted the issue. Ford, who famously transformed the magisterial sandstone rocks of Utah’s Monument Valley into the personification of the American spirit, perversely delighted in eradicating the virgin landscape in this rowdy yet somber tall tale. With the exception of a couple of B-roll inserts and a scene set in a corral, he shot the movie on sound stages utilizing the bright, artificial lighting associated with television. Although it boasted an un-cinematic look, its aesthetic was deeply informed by movie history.

Much of this sensibility derives from typecasting the film’s leads. John Wayne plays Tom Doniphan, an independent rancher determined to confront the hired guns of the big ranches should they provoke him in a direct fight. Since The Big Trail in 1930, Wayne had built an onscreen image based on these two-fisted roles, playing characters who settled their problems in a physically forceful manner. Doniphan faces opposition not just from the goon whose fate is mentioned in the title, but from Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart), a lawyer who aims to replace vigilantism with the rule of law. Both represent the future of Shinbone, the town which serves as the county seat. They also form a romantic rivalry over Hallie (Vera Miles), a feminine symbol of civilization. Although Stewart starred in over a dozen Westerns since 1950, Ford cast him for the association the public had of him playing characters such as the idealistic congressman Jefferson Smith in Frank Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and the quick witted, unarmed town tamer in Destry Rides Again. These men personified the notion that law restrains male aggression without sacrificing order. Wayne and Stewart, by their screen history, present a mythic clash of opposites that Liberty Valance first exploits, then complicates.

The problem with Shinbone’s denizens, to quote David Milch, is that they spin against the way they drive. The town doctor, for example, also runs its funeral parlor, and the newspaper editor, who symbolizes truth, succumbs to drunken flights of fancy. In such an environment, sustained belief in a government by and for the people is suspect, as people are by nature contradictory. Doniphan and Stoddard, however, hubristically deny their binary nature, a notion reinforced by the respective actors’ star histories. Each character believes that their singleminded commitment to principle allows them to transcend the rest of humanity. When the act alluded to in the film’s title occurs, however, they learn that their stated beliefs violate their respective natures, and that they resemble the hoopleheads whose interests they serve. This realization determines each character’s destiny. Stoddard claims false valor to bring order and prosperity to Arizona, and Doniphan internalizes his disgrace through alcoholic self abasement.

By engaging in a blatantly theatrical style, and in drawing upon the audience’s familiarity with its actors’ established on-screen personas, Ford acknowledges that representations of the Old West are performative, not naturalistic. They reveal the dialogic nature of masculine identity that persists in narrative irrespective of historical fact. This film’s specific formula, how a gunfight brought order and civilization to the territory, is a lie, but one that links the importance to storytelling in the creation of a positive national myth. Heroes carry the weight of knowledge so that the public doesn’t have to. The viewer of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance compares legend and history in a way that validates the practice of cultural deception, but it feels less like a betrayal and more like a kindness. When the movie ends with a shot of a wheat field set in a former desert, the lie has value. Progress is real even if the story of how it occurred is not.

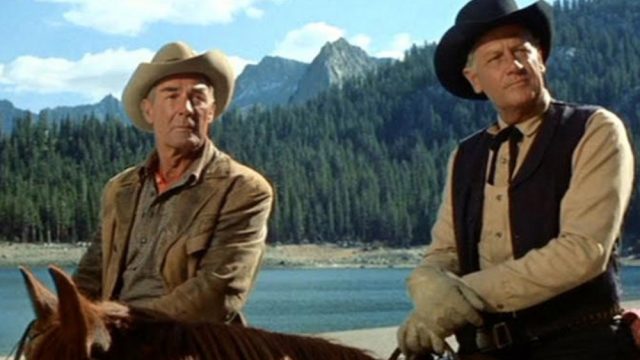

Meanwhile, over at MGM, a younger writer/director of the television era, Sam Peckinpah, also explored the dual nature of traditional heroism through a clash of opposites. As in Ford’s film, Ride the High Country stages a conflict between absolute moral conviction and submission to the rule of law. Like Ford, Peckinpah cast two older actors, Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott, as his protagonists. Like Stewart, both actors displayed range early in their careers. McCrea excelled as a leading man in adventure films and romantic comedies before settling into Westerns after WWII. Scott, in the thirties, performed in supporting roles, usually in costume sagas. As his visage grew craggier, he obtained an authoritative demeanor suited to playing tough lawmen in low to mid-budget Westerns at Warner Brothers and Columbia. Ride the High Country would be Scott’s last feature, and McCrea’s final ride for a major studio.

Peckinpah, however, introduces his actors in a way that subtly mocks their credibility. Steve Judd (McCrea) rides into Sacramento in a dirty and somewhat raggedy suit, carrying a bit of a paunch and needing a shave. When he sees crowds lined up on the thoroughfare he believes they are celebrating his arrival, only to find out that they are actually waiting to watch a horse race a camel. Scott’s character, Gil Westrum, the owner of said camel, dons a gaudy yet tawdry Buffalo Bill carnival costume, disguising the fact that, in his prime, he was a badass lawman. Each character has a separate moral trajectory connected to these costumes: Judd intends to deliver gold from the Sierra Nevada to the bank that hired him, while Westrum intends to join the trek in order to steal it. Judd resembles Raymond Chandler’s description of the modern hero as a knight in soiled armor. Westrum is a charlatan from the get go.

The inevitable clash in agendas emerges through a series of conversations displaying the characters’ differing moralities. Even though Judd will make much less money guarding the gold than promised, he intends to honor his contract. His word is his bond, which he sees in religious terms. As he puts it, he,“wants to enter his house justified.” Westrum laments how men of his professional caliber have been cheated, and feels justified in extracting a concession from the bank as compensation, legal niceties be damned. As the story progresses, these opposing justifications form a complementary bond, allowing for a useful compromise to exist between the forces of righteousness and the framework of the law.

This interdependency first appears in Coursegold, when a blushing bride (Mariette Hartley) discovers, during her wedding reception at the local whorehouse, that she will be serially raped by her husband’s father and brothers. Annulling the marriage requires community consent. Judd feels that he can only abide by the jury’s decision, as protecting Elsa’s virtue falls outside of the boundary of his contract. This weakens his authority, as he accepts constraints on his justification to do the chivalrous, and right, thing. Westrum harbors no such circumspection, and he bullies the judge who performed the ceremony to falsely testify to having a fraudulent law license. The letter of the law is obeyed, but its spirit is violated to serve a morally justified end.

As Westrum’s gold robbing scheme implodes, both men feel both a betrayal of trust and the realization that they cannot morally operate in the world without abiding the others’ beliefs. Criminal acts, however, etch a line in the metaphorical sand on Steve’s part that can’t be crossed. The pursuit of the rapists from the marriage subplot in the third act allows for a reconciliation of opposites, and the bittersweet passing of one of the protagonists. At this point, Ford’s and Peckinpah’s trajectories cross. The moral values of both men coalesce in a climactic scene of violence, with one character left to promote the others’ old-fashioned values in a modernizing world.

In Lonely Are the Brave, modernity is the Old West’s archenemy. Based on a novel by environmental anarchist Edward Abbey, the film depicts the last stand of free-spirited cowboy Jack Burns (Kirk Douglas) whose quixotic attempt to break a friend out of jail leads to an unexpected mountain flight on horseback. The twist here is that this adventure is set in contemporary times, after the era of the lone hero has passed. Burns is an antiquated relic who provokes sympathy from Sheriff Morey Johnson (Walter Matthau) who must nevertheless perform his duty and catch his escaped convict. The symbolically weighted eternal struggle of horse vs. motorized vehicle (and helicopter) ensues, with the latter reaching the trail’s end when struck by a truck full of toilets. This is a blunt metaphor about the antiquated values of American individualism giving way to the crappiness of progress.

Hollywood approached the Western’s decline with a backwards glance towards the creation of its mythology, catering to romantic nostalgia while foregrounding some of the philosophical conflicts inherent in its heroes’ journeys. Lonely Are the Brave accepted a notion that the West, as Sam Shepard would later put it, “is a dead issue.”. Its spirit could only be embodied by those who upheld a sense of tradition in defiance of contemporary convention. By the 1960s this notion became more commonplace. The anarchic-libertarianism of Spaghetti Westerns placed anti-heroes at their center, dissociating the protagonist from traditional values in their pursuit of professional self-actualization. Peckinpah would take up this mantle in the U.S., ultimately succumbing to the self-destructive allure of the maverick individualist. By the eighties the cynicism became fully homoeroticized. Ted Kotcheff’s First Blood, a spiritual remake of Douglas’ film, would launch a string of action genre films starring angry, isolated men defined by their inflated physical muscularity. The style and messaging of Westerns might have been in a tentative stage in 1962, but one sees signs of the genre’s evolution through the purple haze at the twilight of Hollywood’s classic era.