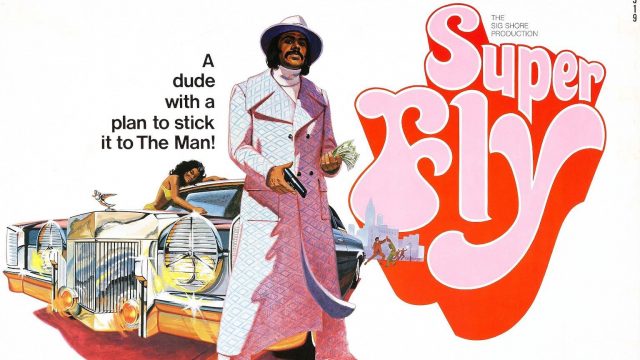

At first glance, Super Fly fits the traditional definition of 1970s “blaxploitation.” It’s set in a ghetto (specifically, Harlem), has plenty of guys dressed to the nines in psychedelic bell bottoms, fedoras, and platform shoes, selling drugs and doing tons of illegal shit, and a gratuitous sex scene in a bathtub. Yet, for numerous reasons, many scholars and critics argue that it transcends the genre. Nearly 50 years after its release, perhaps it’s time to re-assess the film’s genre classification, or perhaps use it as a starting point to further explore a particular, brief movement in American film history.

Like film noir, one can argue that blaxploitation isn’t so much a genre as a chronotrope presenting a specific time and place in a style that is tied to that period. By chronicling Youngblood Priest’s attempt to leave the world of cocaine trafficking (while taking his ill-gotten gains with him), despite the efforts of mafia backed cops to keep him in “the game,” Super Fly’s narrative follows the outlines of the gangster film. Movies defined as blaxploitation often mirrored classical genres, including horror (Blacula, Ruby) and Westerns (the rather unfortunately named Fred Williamson cycle). This mimicry is often used to downplay the movement’s originality, and hence the overall impact it had on film culture.

Linking notions of “quality” or “significance” to originality, however, downplays the role of tradition and continuity to historically analyzing film. The trends of blaxploitation go back to the so called “race films” of the 1930s, where pictures like Harlem on the Prairie and Dark Manhattan adapted formulaic narratives to suit the talents of their all-black ensembles. These films allowed performers such as Louis Jordan, Herb Jeffries, and Mantan Moreland to display their stage and musical talents on screen. They could also exploit a particular novelty or appeal to a particular niche audience. The juxtaposition of African-American talent and unconventional situations, such as having Jeffries ride around Victorville on a horse in cowboy get-up, constituted a certain form of cinematic exploitation. Audiences received some pleasure in witnessing black actors embody archetypes denied to them in traditional Hollywood fare. Technically, “blaxploitation” existed long before the term was officially coined, and prior to its association with sensationalistic portrayals of inner-city life.

The narrative elements of these pictures were of secondary importance, or were viewed a source of unintentional humor in and of themselves. Film scholar Ed Guerrero, in an early study of independent black cinema, recalled the “derisive” laughter audiences gave a Western race film that played in his neighborhood when he was a kid. While these films allowed performers to display their talents in music and comedy, they underscored a divide between the white movie-fantasy narrative of self-actualization fostered by mainstream studios and the black audience who, in a world defined by segregation, was never allowed to participate in that illusion. As Guerrero noted, there was always an ironic response to race exploitation films in which the audience recognized their marginalization, and being condescended to, on screen.

Super Fly’s creation embodies the hallmarks of exploitation film production. Director Gordon Parks Jr. and producer Sig Shore funded the production independently through numerous investors before selling the U.S. distribution rights to Warner Bros. They followed a model developed by Melvin Van Peebles and Parks’ father, the estimable photojournalist turned director Gordon Parks Sr., of financing movies that captured, unlike earlier black-cast films, the intersection of black urban life and the institutions of American power. Economic exploitation in the form of mafia-backed inner-city drug deals and the corruption and brutality of law enforcement represented structural malfunctions in American society as perceived by a subsection of the black experience.

The first wave of the new blaxploitation films initiated a new low-budget filmmaking aesthetic, sporting a look no doubt enhanced by the Parks’ background in newsmagazine photography (there is even a montage sequence covering numerous drug deals done in still photographs snapped by Parks himself). This underscored the sociological awakening of the audience by associating naturalism with consciousness. They favored live locations over sets, and strove for a grittier urban authenticity. The color was desaturated and grey. Super Fly documents the infrastructural decay of what was once considered the cultural capital of the African diaspora with rickety outdoor stairwells, weed-strewn vacant lots and a demoralized, drug-addicted population. Yet for all of these problems, the viewer even to this day uncovers the vibrancy of a cultural resistance to the forces of systemic corruption and neglect. The paisley patterns, outsized fur collars, and platform shoes represent as a defiant expression of identity for the downtrodden, and, most noticeably, the funky rhythms and social consciousness of Curtis Mayfield’s epic score displayed new forces of creativity in the popular African-American arts scene. For all of its hardscrabble rawness, Harlem retains its status as a major cultural center.

In its neorealist-inspired design, Super Fly fulfilled, to a limited (and problematic) degree, the progressive mandate that an independent African-American cinema should present black life as it is experienced rather than imagined in the white American mind. It invented black characters who the audience wants to identify with, whose social conditions are at the center of the narrative as opposed to providing exotic “color” at the periphery. While these goals are clear, their execution was fraught with political controversy, often within the African=American cultural commentariat. Both the NAACP and the National Urban League tried to stop Warner Brothers from releasing Super Fly, expressing concern over how associating black urban life with criminality and glorifying drug dealing as a symbol of racial perseverance would skewer the black image in popular culture. This controversy constitutes a divide in popular tastes: one, dating back to the pioneering, pre-exploitation, African Cinema days of Oscar Micheaux and Noble Johnson, where the black hero was a socially edifying protagonist leading his race progressively forward, and the other, in which one sees a black hero takes on roles reserved for whites in an entertaining, ironic context.

The re-emergence of blaxploitation seemed odd for the genre’s critics, as the mainstreaming of black actors in more middlebrow fare was well underway in Hollywood at the time. Super Fly, for all of its novelty, retained aspects of earlier movies that exploited novelty-driven race content directed at black audiences. One sees this in the melodramatically stylized dialogue and overemphatic performances. Ron O’Neal’s intensity in delivering brutally florid lines like “Give me my money or I’m going to turn your woman out on Whore’s Row. Either way, one of you is going to work,” seems quaintly over-the-top today, but I suspect it was greatly enjoyed as crime-film camp when it played in Times Square in 1972. The film’s swipes at materialism’s centrality to the American Dream and its assertion that drug dealing was “the only game we were left to play” feel both overdetermined in their sociology and poetically overripe. One recognizes a hyperbolic sensationalism in the presentation that amplifies the mise-en-scéne naturalism. Melodramatic excess enhances the popular sentiments concerning the realities and structural causes of the conditions the film shows.

If Super Fly’s theatrical sections delve into mythical self-awareness, Curtis Mayfield’s score, as Mr. Burgundy Suit strongly notes, provides a psychological counterpoint to the drama that gets into the characters’ emotions. These characters engage in little psychological self-confession, as one would expect considering their trade, and the composer’s lyrics integrate elements of social psychology into the proceedings in a manner that is lively but often melancholy. Outside of one sequence at a nightclub where Priest’s main drug connection works, the score is non-diegetic, and the songs play out more or less in their entirety in moments that continually interrupt the pace of the drama for interludes of languorous reflection that often de-glamorize the proceedings. The manner in which this halts the narrative flow feels reminiscent of how the numbers in race musicals suspended the dramatic momentum of their plots. Park’s main contribution to the musical aesthetic of the race film is to push Mayfield’s physical presence to the background, allowing for the music and lyrics to clarify and occasionally counterpoint the images.

Suspending the plot allows room for the actors, particularly O’Neal, to recalibrate their performances in ways that variate and enhance the film’s tone. For example, as Priest drives around in his chrome-plated El Dorado in a dialogue-free sequence lasting several minutes, one senses his wariness of keeping up the illusion of success and the toughness that it requires in his chosen profession. One clearly understands his motivations for getting out of the trade as related to the stress of maintaining his hypermasculine front. Again, Super Fly draws upon exploitation-film aesthetics in new ways, using musical performances to reveal its antihero’s thoughts and conditions in ways that dialectically clash with the manner in which he deals with his customers and colleagues.

Super Fly, like much of ’70s blaxploitation, engages in a playful combination of traditional low-budget independent film tropes and social-realist aesthetics, creating a popular film genre that artfully juxtaposes documentary and performative modes of popular filmmaking. Its sequencing of neorealist authenticity opposite melodramatic flourishes and classical film genre archetypes initiated a unique action-cinema aesthetic, originating within the style of early race exploitation films, that artfully countered liberal taste values about the progressive aims of political filmmaking. The gritty urbanism of this particular film and the ones that followed would profoundly impact the way that mainstream Hollywood would assimilate these images in a more authoritarian style as the decade advanced. These later films took a more law-and-order-based stance to the social problems they depicted, stressing the maintenance of social mores that Priest would undoubtedly find oppressive and absurd.