Conventional wisdom holds that John Wayne wasn’t a great actor. He didn’t display a fastidious degree of craft when practicing his trade, and he didn’t tackle a variety of roles that demonstrated his potential range. Most would admit, at least, that he possessed a certain presence, an inherent grace, in the way that he moved and spoke. He was often the most authentic presence in the vehicles in which he performed, and his casually authoritative demeanor often inadvertently exposed the aesthetic artifice of the various enterprises to which he dedicated his services.

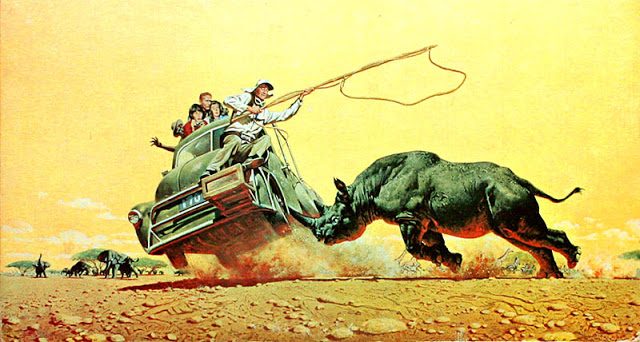

One could make the case that Hatari! best exemplifies Wayne’s charisma, for he seldom appeared in a movie whose grip on Hollywood storytelling structure seems so tenuous. If director Howard Hawks took a perverse delight in transforming a B-Western premise into a nearly 2 ½ hour “hangout” movie in his previous opus, Rio Bravo, he really went for broke here in privileging digression over plot. As the viewer lounges around with a group of hunters on an African gaming reserve for almost three hours, we experience the ebb and flow of a cloistered life segmented into activities like romancing the few white women and dashing out into the wild to capture animals for American zoos. Although the crew faces a contractual deadline to deliver its prey (making this an interesting dialogic companion to Gone in 60 Seconds), the urgency of a “beat the clock scenario” never really enters the lackadaisical rhythm of this colonial idyll.

When focusing on the mechanics of Big Game trapping, Hatari! exhibits a certain documentary-like realism, in large part because the filmed footage was largely improvised based on what kinds of animals came by, and how they responded to being pursued, on the days they were being filmed. It revels in representing the group’s esprit de corps of “doing the job right” in meticulous detail that one saw in late 60s-70s nature documentaries like Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom. This quality connects it to other films in Hawks’ canon, which are mostly comprised of character-driven adventure stories featuring men in dangerous occupations located at the edge of civilization.

Most genres that romanticize the exploits of professional elites are built on the old adage, “If you want to make God laugh, tell Him your plans.” Schemes that, on paper or diagrams, seem foolproof fall afoul due to unforeseen circumstances, creating dramatic momentum. Said complications require sacrifices born of the consequences of committing one’s identity to the group’s instrumentalist ethos. In Michael Mann, divine mirth is tragic, where adherence to the professional ethos reveals a selfish flaw in the personality of his heroes. In Peckinpah and Huston, laughter is a defiantly caustic and cynical expression of resistance to the futility of instrumental reason . With Hawks, there is a detached, almost Shakespearean embrace of chaos, expressed here not only in the unpredictability of animal behavior but in the presence of women, whose pulchritude challenges the self-contained essence of masculine power to tame nature’s wildness.

The episodic and varied outcomes of the hunt express the film’s acceptance of the limits of professional outcomes. The Indian’s (Bruce Cabot) mauling at the horn of a fleeing rhino exposes the truth that small errors result in injury, and that age and circumstance connected to a life of danger limits the time in which one can commit to the cause. Wayne makes a somewhat exasperated speech shaped in that knowledge after the accident, but as these outcomes are part of the world, and the choices, that he lives in, he moves on. Sometimes even the craziest of plans, such as Pockets’ (Red Buttons) Rube Goldberg-like plan to use rockets and a huge net to cover a tree teeming with dozens of monkeys, go unexpectedly right, further lending a sense of unpredictability to the proceedings. The failure or success of plots to succeed and fail in most movies, like a heist film, implies a certain ethical assumption as to the motive of the scheme. Good plans fail if they are morally wrong. In Hatari! there is no underlying moral because all outcomes are variable. The characters just live through this.

The film dispenses with any pretense of dramatic tension when it heads back to the proverbial ranch, indulging in light romantic comedic banter and low-stakes macho posturing for women. Brightly lit so as to extinguish any hint of a shadow, these scenes offer formulaic comic relief in the form of a sexy Italian photographer nicknamed Dallas (Elsa Martinelli) whose appearance upsets the natural (mostly) homo-social order established within the professional community. In the romantic subplots in Only Angels Have Wings, To Have and Have Not, and Rio Bravo, the group leader squares, then pairs, with women who hold their own in the adventurous environment without compromising their femininity. Dallas, alas, initially seems out of place in this manly universe, and the movie aims way too much slapstick comedy at her expense.

On the other front, Brandy (Michelle Girardon), the owner of the encampment, is pursued by two members of her burly crew (Hardy Kruger and Valentin de Vargas), but chooses the diminutive, and slightly effeminate, Pockets instead. As in Bringing up Baby and Monkey Business, Hawks upends the conventional notion that the life force lies solely with masculine strength. The point is a bit undermined by Girardon’s flat performance resulting from her speaking her English dialogue phonetically. Martinelli’s limited English likewise hampers her performance as well.

(Needless to say, the sexism here is matched with a variety of antiquated representations of Africans and depictions of what now would be called animal cruelty. One’s ability to appreciate the virtues of this movie depends on a huge ability to overlook these factors)

Wayne’s laidback gravitas grounds these proceedings to a recognizably human natural environment, even as his co-stars Hardy Kruger and Valentin de Vargas stiffen under Hawks’ somewhat distracted gaze. He may be the celibate Fuhrer who keeps the compound in order, but he seems to accept that he’s gonna get laid. With the dramatic tension being set so low, Hatari! is a perfect gateway into understanding Wayne’s persona. Even at his most conventionally masculine, he can, in this, the most Seinfeldian of laidback adventure films, be set up for gentle laughs.