There must have been something in the water in 1948. Maybe it was the combination of the gloom of black-and-white film with the inherent artificiality of adapting theater. Maybe the German Expressionists were in vogue with the same highbrows who’d adapt the Bard after the fall of a regime that suppressed them as “decadent art.” Or who knows, maybe Dr. Caligari just got bored with his studies on sleepwalking and dusted off the old Complete Works of Shakespeare. One way or another, Orson Welles and Laurence Olivier’s shadowy, nightmarish Shakespeare adaptations seem like twins separated at birth, a two-film movement of Shakespearean Expressionism.

Both films open in a deep fog, setting everything in a dreamlike haze. It’s also the first of many images across both movies that connect them to German Expressionism’s previous Hollywood legacy in the horror genre. As Hollywood soaked up talent from filmmakers fleeing the growing shadow of German fascism, many of the makers of the great Expressionist films – including cinematographers Karl Freund, director of The Mummy, and Edgar G. Ulmer, director of the Karloff/Lugosi masterpiece The Black Cat – set the tone of the American horror film. That’s a tone Macbeth and Hamlet are well steeped in, and the next shot of Hamlet suggests Olivier has done his homework in tracing his style back to the source: a moody matte painting of the Castle Elsinore, as crooked and twisted as the city streets in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

The voiceover describes what we’re about to see as “the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind.” While this suggests a much shallower reading of the play than we’re actually going to get, it still serves a valuable purpose: it announces that we’re going to be deep inside the subjective world of Expressionist art. At one point, we literally go inside Hamlet’s “mind’s eye” (a phrase that may have originated with the play) as he imagines his father’s murder.  As a result, Hamlet takes place neither in the “stagy” world of the theater nor the realistic world of most film adaptations. This is an archetypical nightmarescape, Castle Elsinore as Castle Frankenstein. The setting isn’t exactly a character as the old cliche goes, but it’s not just a backdrop either. There are frequent long takes of the camera gliding through the stony corridors, drinking in all the shadows and crags.

As a result, Hamlet takes place neither in the “stagy” world of the theater nor the realistic world of most film adaptations. This is an archetypical nightmarescape, Castle Elsinore as Castle Frankenstein. The setting isn’t exactly a character as the old cliche goes, but it’s not just a backdrop either. There are frequent long takes of the camera gliding through the stony corridors, drinking in all the shadows and crags.

Olivier wears Hamlet’s traditional black, suggesting his dark inward state outwardly, but he also uses the filmic toolbox to give him extra contras with the innocent, pre-madness Ophelia, with her literally radiant white dress and fair hair.

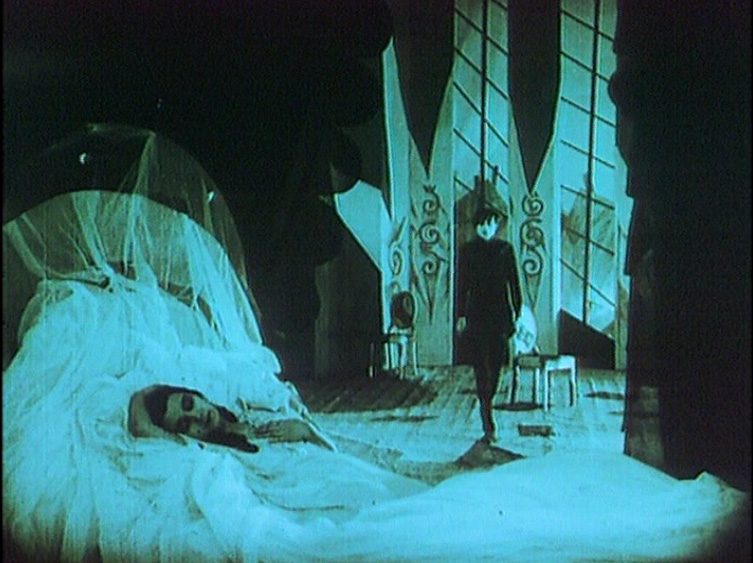

And when Hamlet somnambulistically stalks in on her to convince her he’s gone mad, Olivier swipes the staging almost frame-for-frame from Caligari.

And when Hamlet somnambulistically stalks in on her to convince her he’s gone mad, Olivier swipes the staging almost frame-for-frame from Caligari.

And later, Hamlet stalks up the stairway, his shadow trailing ahead of him just like Nosferatu’s.

If Olivier’s taking his inspiration from German and American horror, it’s only fitting he finds his best outlet in the scenes where Hamlet becomes a ghost story. This is where his artistic imagination and hallucinatory subjectivism really gets to shine. The ghost’s entrance seems to upset the very film it’s printed on, as Olivier experiments with the focus going in and out with the rhythm and soundtrack of a pulsing heart.

And if that sounds avant garde, it’s nothing next to the psychedelic freakout of the “To Be or Not to Be” monologue, with waves beating against the shore turned abstract by soft focus camerawork and strange shadows, before dissolving into another literalized image of the mind’s eye.

And if that sounds avant garde, it’s nothing next to the psychedelic freakout of the “To Be or Not to Be” monologue, with waves beating against the shore turned abstract by soft focus camerawork and strange shadows, before dissolving into another literalized image of the mind’s eye.

Just as much as the horror elements, this scene of Hamlet’s inner turmoil provides another opportunity for Olivier to showcase his Expressionist inclinations. The medium shift allows him to play the scene with an intensity that would be impossible onstage. Like Welles, he can use voiceover to let us in on on the secret thoughts his characters can’t say out loud. And he can push his camera uncomfortably close to Hamlet’s face, before pulling back with jump-scare quickness as he’s shaken out of his navel-gazing by the cosmic question of life after death.

Just as much as the horror elements, this scene of Hamlet’s inner turmoil provides another opportunity for Olivier to showcase his Expressionist inclinations. The medium shift allows him to play the scene with an intensity that would be impossible onstage. Like Welles, he can use voiceover to let us in on on the secret thoughts his characters can’t say out loud. And he can push his camera uncomfortably close to Hamlet’s face, before pulling back with jump-scare quickness as he’s shaken out of his navel-gazing by the cosmic question of life after death.

This is a black and white film with far more black than white. The play-within-a-play takes place in almost total darkness, and as Hamlet announces “the play’s the thing!/With which to catch the conscience of the king!” he jumps with a campy theatrical flourish, lit by a lone spotlight, reminding us that the outer world of the movie set is itself a kind of stage.

The final image of the film would have been equally at home on the poster for a Dracula film or a Weimar art gallery: hunched silhouettes carrying Hamlet’s corpse to the top of a Gothic ruin against a dramatically contrasting sky.

The final image of the film would have been equally at home on the poster for a Dracula film or a Weimar art gallery: hunched silhouettes carrying Hamlet’s corpse to the top of a Gothic ruin against a dramatically contrasting sky.

Orson Welles, another Shakespearean actor turned filmmaker, takes the Shakespressonist aesthetic, like he does everything, much farther than anyone else dared. Macbeth, a strong contender for the most underrated movie he ever made, is a masterpiece dark, doom-laden atmosphere. The first scene, of the witches hunched over a craggy, precarious cliff, sets a mood of waking nightmare Welles will sustain throughout the length of the film.

Orson Welles, another Shakespearean actor turned filmmaker, takes the Shakespressonist aesthetic, like he does everything, much farther than anyone else dared. Macbeth, a strong contender for the most underrated movie he ever made, is a masterpiece dark, doom-laden atmosphere. The first scene, of the witches hunched over a craggy, precarious cliff, sets a mood of waking nightmare Welles will sustain throughout the length of the film.

In Welles’ minimalist style, the Weird Sisters are iconic figures, their faces invisible even when they’re not lit in silhouette, posing on geometric formation with forked staffs of unknown purpose, like something out of primitive art.

Their existence is going to add an element of the supernatural to any production of Macbeth, but Welles doesn’t stop there. Where Hamlet was an epic in a chintzier, more Hollywood sense (Olivier can’t resist stopping the action for a few Ben Hur-style processions, complete with trumpet fanfare), Welles uses every penny of his own, smaller budget to make Macbeth epic in the primal, mythic sense. His adaptation emphasizes the cosmic significance of Macbeth’s blasphemous act of regicide. This artistic choice is evident in the heightened, mythic drama of Macbeth’s look and feel, but also in more specific details. The rightful kings of Scotland march with soldiers carrying a thicket of strange, spindly crosses that wouldn’t be out of place in a painting by Edvard Munch or Egon Schiele, or in a cartoon from our most prominent latter-day Expressionist, Tim Burton:

Their existence is going to add an element of the supernatural to any production of Macbeth, but Welles doesn’t stop there. Where Hamlet was an epic in a chintzier, more Hollywood sense (Olivier can’t resist stopping the action for a few Ben Hur-style processions, complete with trumpet fanfare), Welles uses every penny of his own, smaller budget to make Macbeth epic in the primal, mythic sense. His adaptation emphasizes the cosmic significance of Macbeth’s blasphemous act of regicide. This artistic choice is evident in the heightened, mythic drama of Macbeth’s look and feel, but also in more specific details. The rightful kings of Scotland march with soldiers carrying a thicket of strange, spindly crosses that wouldn’t be out of place in a painting by Edvard Munch or Egon Schiele, or in a cartoon from our most prominent latter-day Expressionist, Tim Burton:

but when Hamlet takes over, his own soldiers trade these religious symbols for demonic pitchforks.

but when Hamlet takes over, his own soldiers trade these religious symbols for demonic pitchforks.

When Macbeth and MacDuff finally clash, Welles uses expressionistic techniques to shoot them like pagan gods from mortal’s-eye view, larger than life, radiating light that obscures them rather than illuminating them.

When Macbeth and MacDuff finally clash, Welles uses expressionistic techniques to shoot them like pagan gods from mortal’s-eye view, larger than life, radiating light that obscures them rather than illuminating them.

Even one of the most unfortunate design choices, Welles’ boxy, rabbit-ear-looking crown, adds to Macbeth’s supernaturally-shadowed appearance, making him appear to have devils’ horns.

Even one of the most unfortunate design choices, Welles’ boxy, rabbit-ear-looking crown, adds to Macbeth’s supernaturally-shadowed appearance, making him appear to have devils’ horns.

The supernatural emphasis leads to a beefed up role for the court priest, who, in the only addition to Shakespeare’s text, recites these lines from the Catholic liturgy: “Do you renounce Satan and all his works?” to the response “I renounce them.” Macbeth, pointedly, is somewhere offstage.

Hamlet’s castle may have been spooky and Frankensteinian, but it was recognizable the work of a human hand, grounded comfortably in the civilized world. Castle Macbeth seems to have bubbled up from the earth, full of craggy rock formations that don’t seem to serve any human purpose. Or look at these jagged, unfunctional spikes that seem to serve no purpose at all, except to emphasize the castle’s uneasy atmosphere.

Or look at these jagged, unfunctional spikes that seem to serve no purpose at all, except to emphasize the castle’s uneasy atmosphere.

Much of the Macbeth family’s secret plotting takes place in the caves beneath the castle. Violent, primitive desires, discussed in literally subterranean secrecy.

Even King Duncan’s bedroom, which we would expect to be a place of comfort and luxury, is a sparsely furnished nook carved out of unforgiving living rock. And Welles, like Olivier, casts his actors’ Nosferatu shadows over the space.

Lighting tricks like these show few bows Welles makes to literal reality to emphasize the story’s emotional reality. If the scene calls for it, he’s not above shoving a light right under an actor’s face like a kid telling a campfire story.

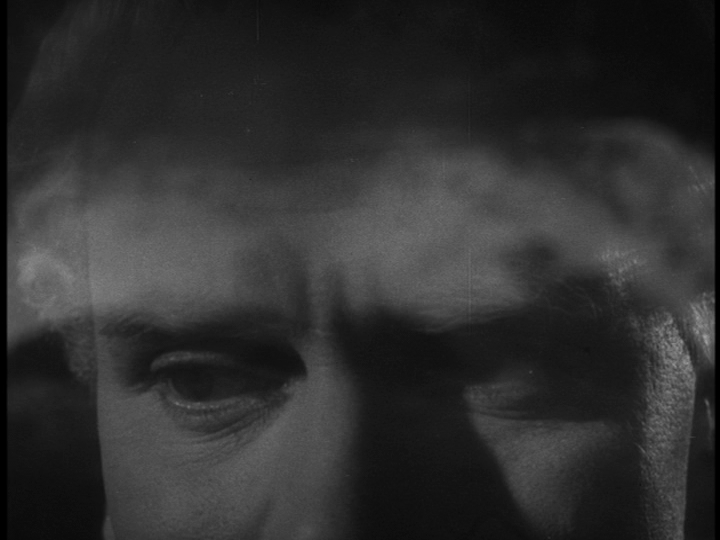

In his pursuit of Expressionistic intensity, Welles forces his audience right into the faces of his stars and the emotions they express. This applies most of all to his own face as he contemplates the ghost of Banquo, every tear and drop of sweat glistening right in the viewer’s face.

In his pursuit of Expressionistic intensity, Welles forces his audience right into the faces of his stars and the emotions they express. This applies most of all to his own face as he contemplates the ghost of Banquo, every tear and drop of sweat glistening right in the viewer’s face. Shakespeare’s plays aren’t “realistic” the way modern fiction is. While many great filmmakers have succeeded in grounding his works in visible reality, Olivier saw the way to frame it in a far less literal but far more intense subjective reality, and Welles took that idea and ran with it. In their archetypical interpretations, they preserve the universal realities of their source that have allowed it to endure across centuries as works that seem more “real” in their specifics are forgotten.

Shakespeare’s plays aren’t “realistic” the way modern fiction is. While many great filmmakers have succeeded in grounding his works in visible reality, Olivier saw the way to frame it in a far less literal but far more intense subjective reality, and Welles took that idea and ran with it. In their archetypical interpretations, they preserve the universal realities of their source that have allowed it to endure across centuries as works that seem more “real” in their specifics are forgotten.