That’s a diverse and distinguished stew of influences, but one of the most important is Garth Ennis. The Irish author of comics like Preacher, The Punisher, and The Boys is Jason Aaron’s closest forebear: he balanced the seemingly irreconcilable extremes of grim realism and flights of cartoon fantasy, sadness and violent anger, stoic toughness and effusive tenderness, in ways that Aaron has followed and frequently surpassed.

The fantastical inventiveness isn’t as present as in Scalped as most of Aaron’s other work (like his sadly brief run on Wolverine and the X-Men, which may be my favorite comic book of all time, and certainly the most purefully, joyfully comic-booky one ever created). This isn’t the Marvel Universe, but something much closer to our own. There’s no space sharks or Frankenstein murder circuses here. But Aaron still finds ways to exercise his imagination here, even if he mostly draws from the relatively grounded genres of pulp fiction and grindhouse film, the source of Dash’s trademark nunchucks. There’s characters here that could have stepped off one of those grungy B-movie screens, like Mr. Brass, a tiny, one-armed Hmong hitman who looks and talks like a professor but conducts deadly business with a bag of surgical tools. So could the gloriously delirious chase scene between Diesel on horseback and Dash in Merle Haggard’s stolen tour bus that ends in a fight on the rodeo grounds between Diesel, Dash, and an angry bull. The series climaxes in an even more over-the-top setpiece, but by then it’s passed camp and reached the realm of the mythic.

SPOILERS begin here

The same could be said of Scalped’s more explicitly fantastical elements. Catcher, who we learn in his final moments, “wanted to be a writer. To write stories about elves and dwarves and heroes on epic quests,” frames his own story in the same way, trying to mentor Dash, who he sees as something like one of those stories’ Chosen-One heroes, who “will lead the Rez out of the darkness.” The real story is about as far from fantasy-paperback kitsch as you can get: like Fanny and Alexander, Scalped makes the supernatural seem totally natural. Gina comes to Dash to deliver a final message moments after her death, and her spirit animal leads the purehearted officer Franklin Falls Down through a death trap after Catcher dares him to find his way blindfolded. Images like that trap, the glowing-eyed feral dogs that follow Catcher in the story’s final act, or the burning casino where it all ends, aren’t explicitly supernatural, but they still have the air of myth, somewhere between Bosch and the B-movies. It’s completely unrealistic to imagine how Catcher could have gotten the resources and wherewithal to put all this together. But it makes a deeper kind of sense that makes all those questions irrelevant.

Aaron is an atheist, and while his comics feature the expected religious bigots and evil angels, many others show religion in a far more positive light. He portrays the faith of characters like X-Men’s Nightcrawler and Angel with deep respect and even envy, and he uses Thor to envision the kind of god he could believe in. Red Crow seems to belong to the second category, and his faith eventually saves him. But part of what makes Catcher such a fascinating character is the difficulty of pigeonholing him and his faith as a positive or negative force in the story. We eventually learn that he’s responsible for both the book’s titular scalpings: of the FBI agents Nitz is so dead-set on avenging, and of Gina Bad Horse when she appeals to him to come forward so the man who’s spent the past thirty years in prison for his crime can go free.

And yet, even when we learn that, it’s hard to hate him. Part of it’s his dry sense of humor — he claims Dash is Iktomi, the Spider Trickster, but he has more than a few trickster qualities himself. And part of it’s the strength of his vision and the torment it causes him. He has a bit of a god complex that he uses to justify horrible crimes: even after killing Gina, he claims it’s all part of his destiny, and his first solo story is called, “A Thunder Being Nation Am I.” But that same story ends with these words: “This is the story of a mighty vision given to a man too weak to use it.” And indeed, his visions seem to be genuine. In that story he catches a glimpse of the most significant events in the series through the end of its run. He sees the spirit animals of the people he meets, visions that will later be confirmed in their own vision quests — including one of the most haunting images in the series, and the one that shocks Red Crow into changing his ways, the chief chained to the flayed corpse of his spirit animal. It’s a fitting metaphor for a man who’s sold his soul and heritage for material success. Red Crow talks a big game about traditionalism, but we see the depths of his compromise in how he sells it out for the gaudy Crazy Horse Casino, posing with showgirls in “traditional costumes” that are about as accurate as Cher’s. He claims to do it for the good of the tribe. But the influx of drugs and thugs he’s welcomed to its borders seems leaves it worse than he found it.

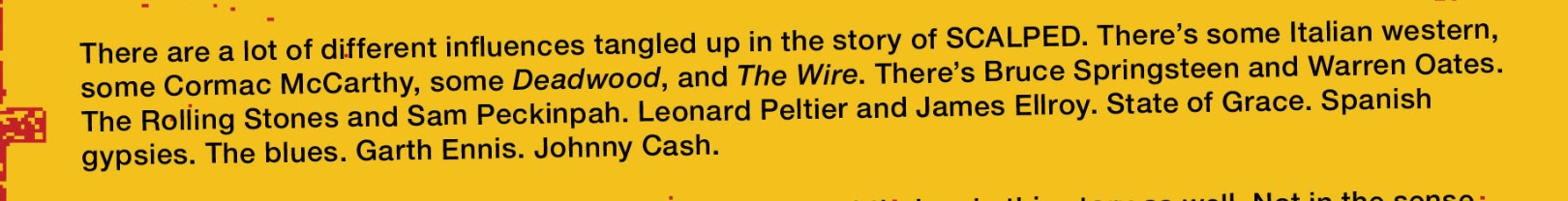

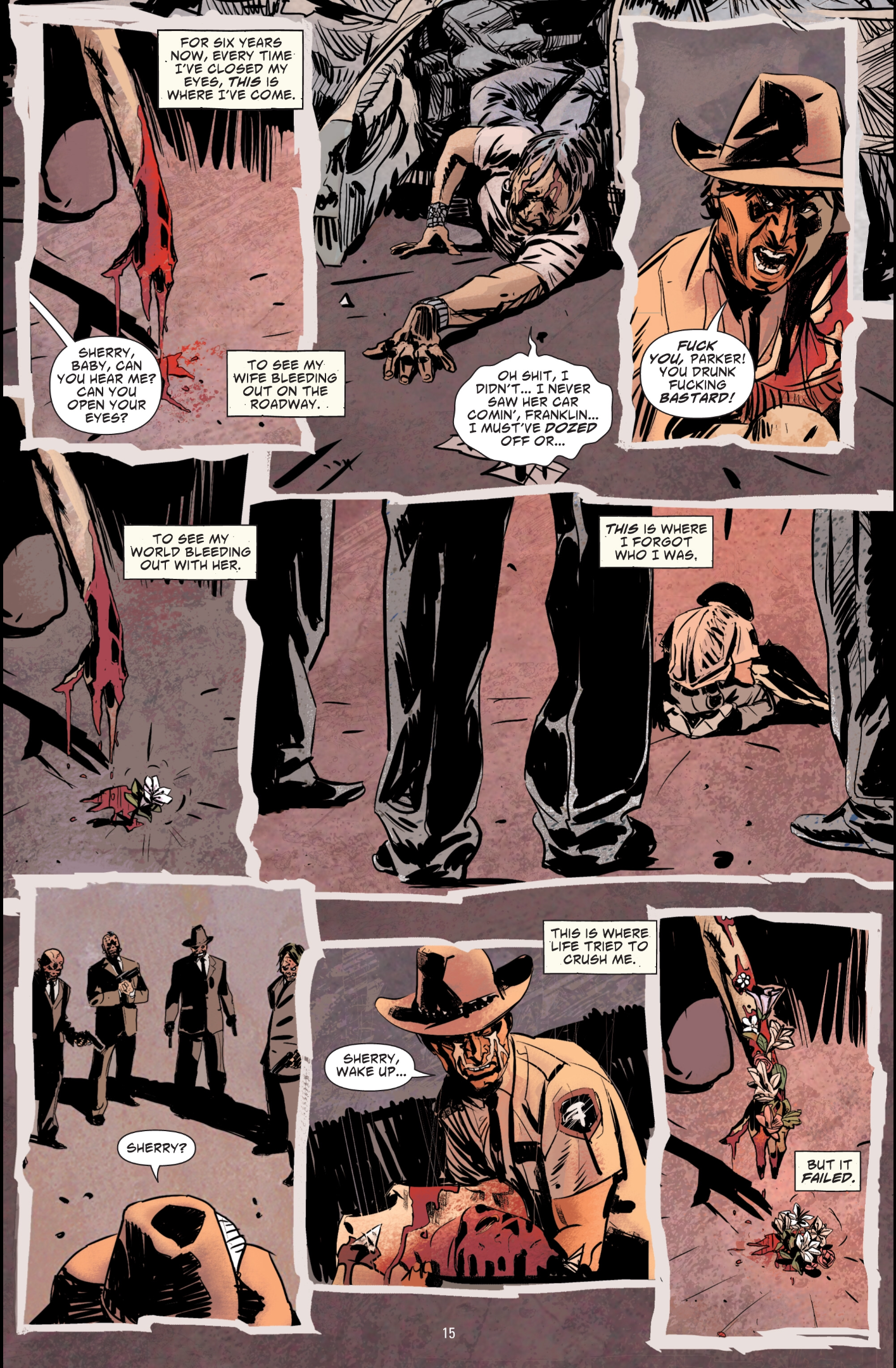

But Ennis and Aaron’s other paradoxes that drive their emotional stories of men who refuse to show emotion are even more essential to Scalped’s power. One of the most popular definitions of toxic masculinity is the inability to express any emotion other than violent anger. If that’s the case, the cast of Scalped is full of poster boys for the phenomenon. Aaron explores it most powerfully in the aftermath of Gina Bad Horse’s death. In Dead Mothers, Dash learns what happened to her and refuses to acknowledge it, either by taking time off or investigating the murder in his role as tribal cop. Instead, he throws himself into the case of a dead sex worker and the care of her surviving children. He learns that Diesel is responsible, but also that he’s untouchable as a fellow undercover agent. Caught between his desire for justice and his own safety, Dash is paralyzed, forced to give the dead woman’s son Shelton false reassurances while knowing there’s nothing he can do. Most comics writers are in love with bombastic spectacle, either visual or verbal, but Aaron and R.M. Guera know the best way to hit readers in the heart is with simple, devastating silence, as when Dash tells the kids what happened to their mother, or when Shelton is laid to rest in the morgue.

Or, in other cases, using as few words as possible, mining more emotion from what isn’t said than what is.

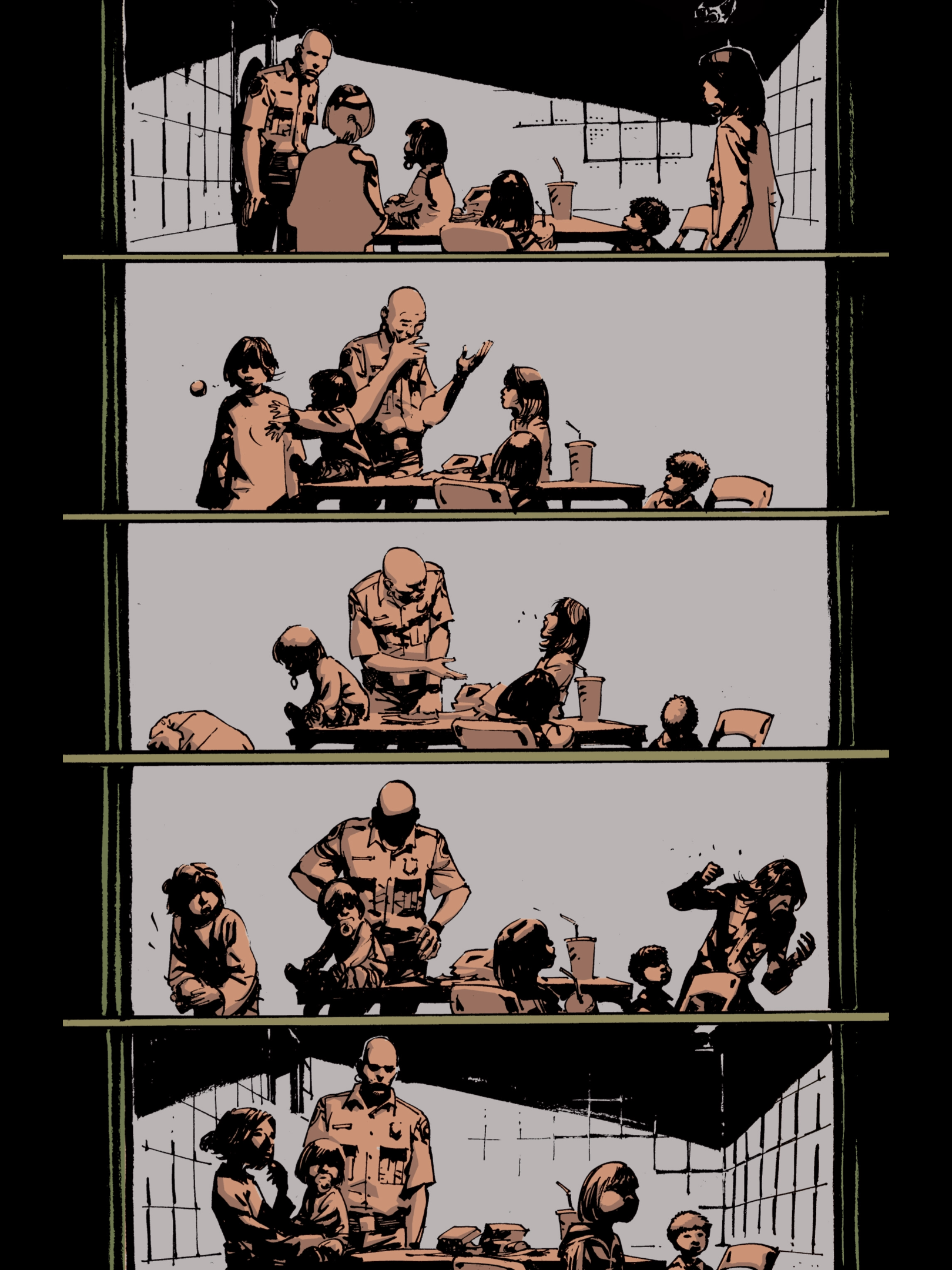

In The Boudoir Stomp, we see Dash, after the child’s death, finally collapsing in his grief, looking for solace in sex and drugs. Carol, his source of both, had been a fairly shallow and, frankly, sexist “bad girl” up until this point. But in this story, we learn that she too, has her reasons for her lifestyle. She had once been married and expecting a baby, until her husband stole from her father, who murdered him in a shootout that cost Carol her child. Davide Furnó takes over on art duties for this storyline, and he perfectly captures the crippling sorrow in her face.

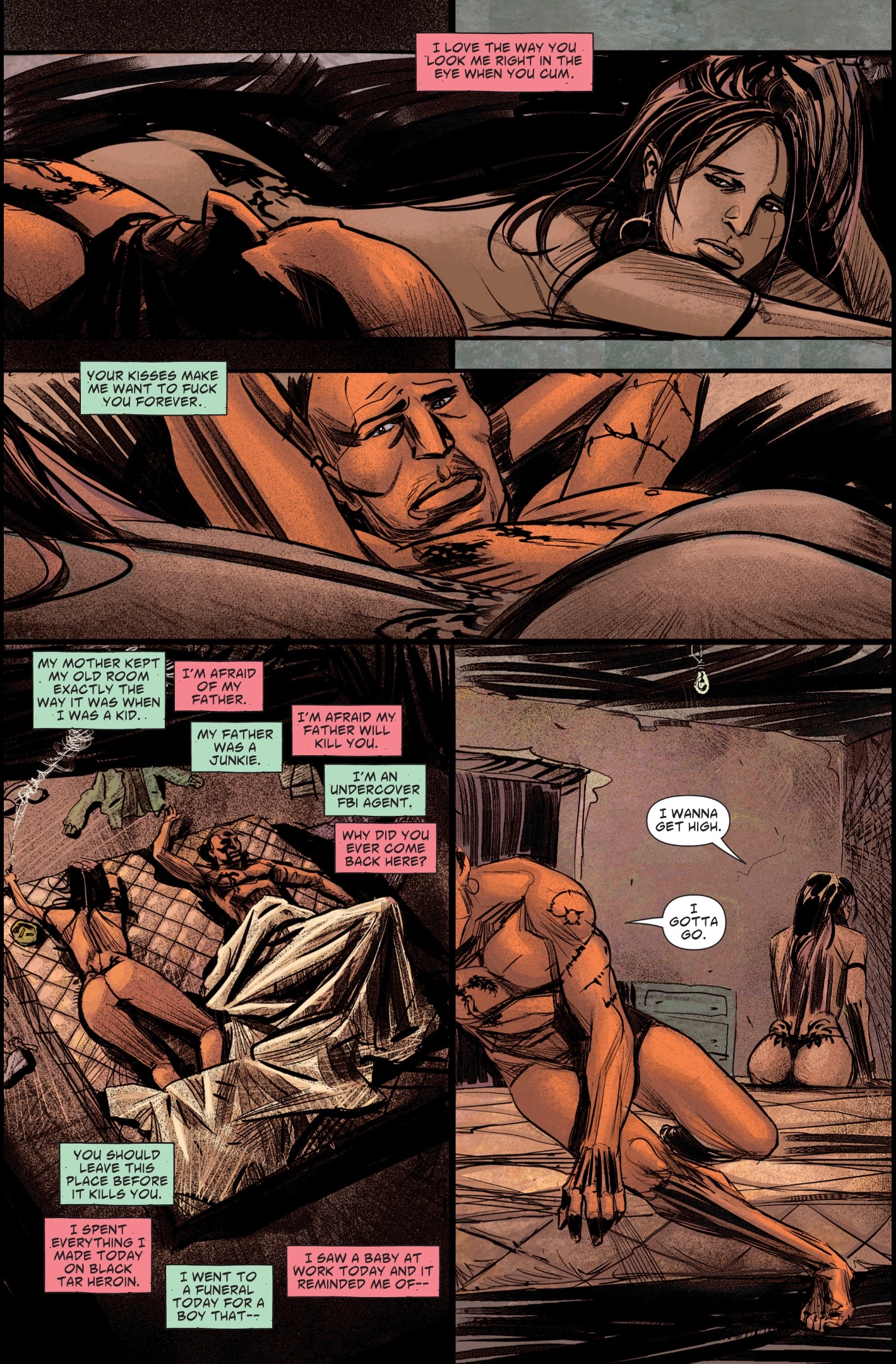

He’s also responsible for another moment of devastating minimalism in a flashback to the moments right after Carol’s miscarriage, as she sits on a bare mattress smoking black tar heroin, baby clothes scattered across the floor.

These two stories, together with Red Crow’s own response to Gina’s death in The Gravel in Your Guts give Scalped an early peak. Unfortunately, it’s followed by a valley in High Lonesome, which, despite giving us the glimpses into the souls of Nitz and Diesel’s I mentioned yesterday, is also Scalped’s deepest wallow in pointless ugliness, including the casual murder of a sex worker that serves little purpose either for the murderer or to the narrative. Fortunately, Scalped regains its mojo as it enters its second half, and from there it’s a nonstop ride to the finish.

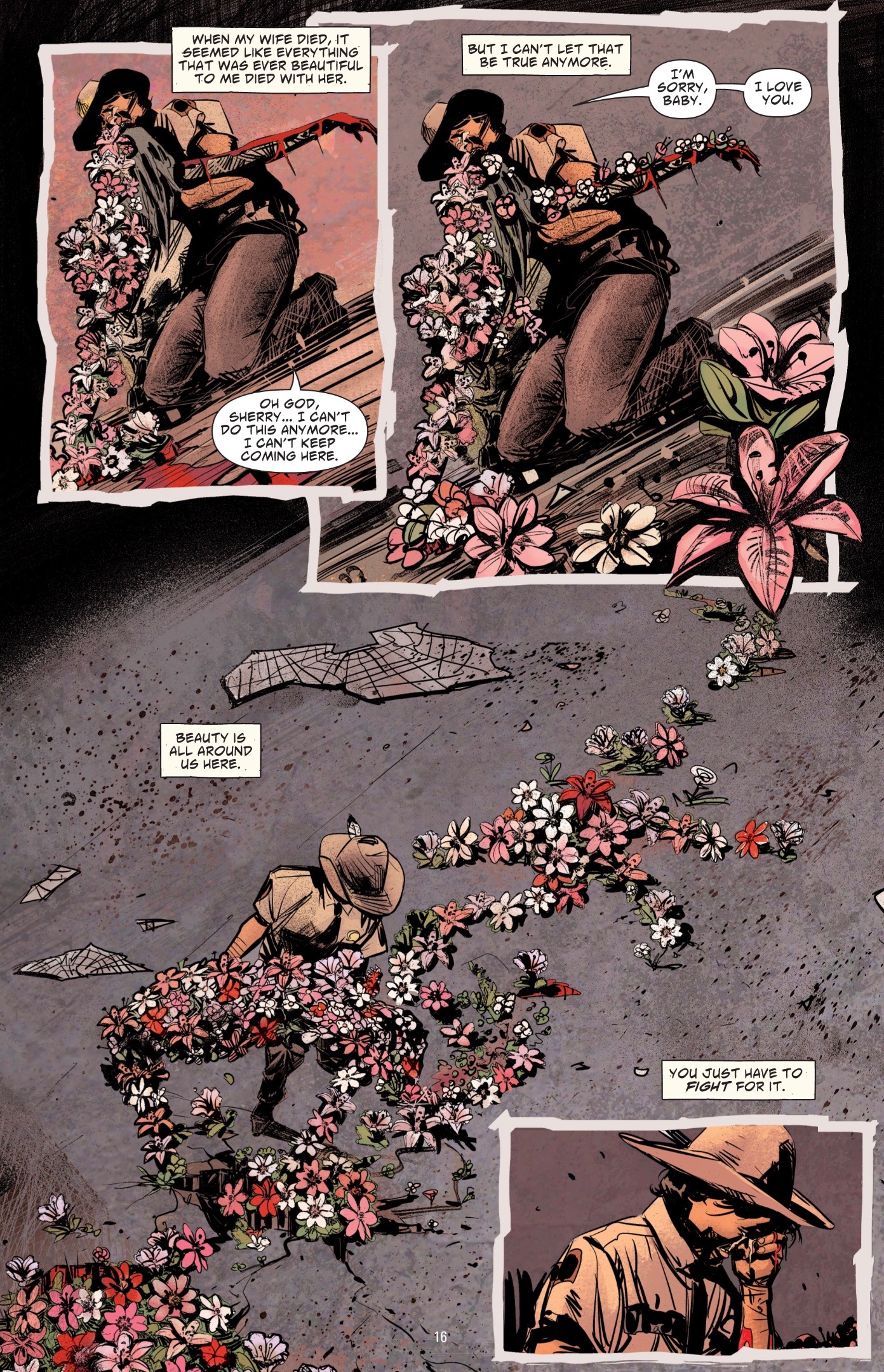

Tribal Officer Franklin Falls Down serves as an alternative to Red Crow and Bad Horse’s icy machismo. He’s coded feminine, with his love of romance novels and soap operas. But in all the important ways, he’s the strongest character in the series. (And while far too many women in this series including Franklin’s wife, exist only to suffer violence and decorate the backdrop, it’s telling that the two other contenders for Falls Down’s title are both women: Gina Bad Horse and Granny Poor Bear.) He’s the archetypical One Good Cop who can’t be bought or sold. But he’s more than that, and as he visits the sweat lodge in one of the most startlingly hallucinatory scenes in the series (drawn by guest artist John Paul Leon) he delivers what might as well be its thesis statement.

The message here is far from the “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” optimism of most fiction, and Aaron’s decision to gaze right into the horror of the world and still see past it is one of its strongest qualities. The message isn’t that every little thing is gonna be alright; instead, we can make it right if we’re willing to bleed for it. This sequence is a rebuke to the rest of the cast, Red Crow in particular, who believe cruelty is necessary to survive in a cruel world. After his vision of his dead spirit animal and the realization he would let his beloved mentor die of a heart attack to secure his political position, he does what he can to find what he has lost. In moments of biblical power, he literally burns down his meth houses.

The message here is far from the “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” optimism of most fiction, and Aaron’s decision to gaze right into the horror of the world and still see past it is one of its strongest qualities. The message isn’t that every little thing is gonna be alright; instead, we can make it right if we’re willing to bleed for it. This sequence is a rebuke to the rest of the cast, Red Crow in particular, who believe cruelty is necessary to survive in a cruel world. After his vision of his dead spirit animal and the realization he would let his beloved mentor die of a heart attack to secure his political position, he does what he can to find what he has lost. In moments of biblical power, he literally burns down his meth houses.

In keeping with Aaron’s love of his most seemingly insignificant characters, Red Crow’s redemption runs in parallel with that of Wooster T. Karnow, sheriff of the neighboring town of White Haven. He brags to anyone who’ll about his nonexistent service in Vietnam and his Chuck Norris-style showdowns with armed goons, but in truth he’s content to accept kickbacks from Red Crow and Nitz and threaten imprisonment to get sexual favors. In “A Come-to-Jesus,” machismo turns out to be a positive force in his life: confronted by a real man, in the person of a US Marshal who arrests a gun-toting criminal while Karnow lies passed out on the ground. Karnow tries to assert himself when the criminal laughs at him, nearly shooting him point blank. The marshal’s response and Wooster’s reaction (as drawn by Jason Latour, another guest artist who would reteam with Aaron for Southern Bastards) are devastating:

Wooster comes back from his experience with integrity in place of his old bluster, pursuing justice but choosing compassion over violence. In one poignant moment, he tells Dino Poor Bear (the daydreaming teenager from Casino Boogie), “Anyone can change.” Depending on how you look at it, Wooster either stays true to himself to the end or pays the price for his macho posturing when Dino guns him down a few issues later. But it’s significant that his last words are an attempt not at domination, but reconciliation: “Go home, son. I know you want to.”

Nearly every character undergoes some kind of transformation in Scalped. After a bait-and-switch internal monologue about her past suicide attempts, Carol ritually kills her past self by setting her house on fire with everything she owns inside. Other characters refuse to change. Nitz hits rock bottom, and when a stroke of fate puts him back on top, he goes right back to his old ways. Catcher seems to realize the enormity he’s committed and offers Dash the chance to take revenge on his mother’s killer. When Dash takes that offer over the alternative of saving Falls Down, Catcher chickens out, rationalizing the Dash failed his moral test, and tries to kill him instead.

Other characters change for the worse. Dino’s introduction in the moving “Ambitions az a Ridah” section of Casino Boogie paints him as one of the most sympathetic characters in the series, doing everything he can to provide for his infant daughter, whose mother is nowhere in sight. The compromises he makes to that end lead him deeper into a life of crime. He reaches a turning point when Carol comes to live with the Poor Bear family and he becomes infatuated with her. He is, if not friendzoned, then “brother”zoned, to use Carol’s words. Aaron stops short of blaming Carol: “I don’t believe in victims. Folks choose their direction. No matter what they been through. No matter how their upbringing. No matter what sorta shit life throws at ‘em.” But it’s still an ugly and unconvincing explanation for Dino’s turn to the dark side.

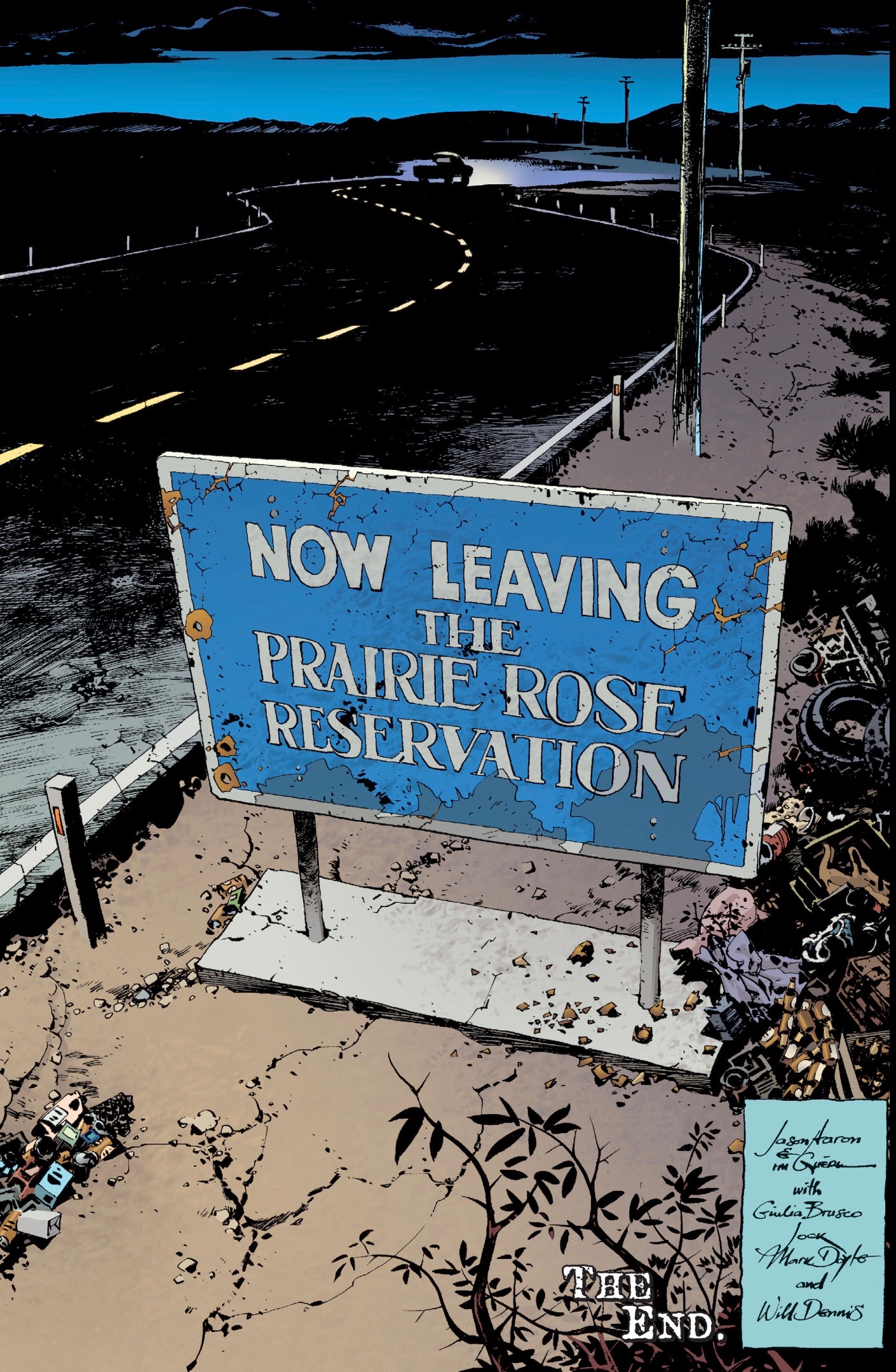

Nevertheless, it makes him a part of the cyclical fatalism of Scalped’s epilogue. Dino becomes the new Red Crow; Red Crow becomes a kinder, gentler Catcher, even taming his wild dogs; Carol becomes the new Granny Poor Bear after the old woman’s death. But before we can get there, Aaron has to deliver his promised shitstorm. It happens the only way it can: in the flaming wreckage of the Crazy Horse Casino, set alight by Dino and his gang in a blaze that makes all the other symbolic house-burnings look like candle flames, as Red Crow, Catcher, Bad Horse, and Nitz converge, each one seeking revenge on the others. Some get it, and pay for it with their lives. Others walk away, but they walk away changed. Tearing through the last four volumes in a plane ride, I walked into the airport in a daze at the power and intensity of what I’d just seen. The series ends where it began, with a highway sign informing us “You Are Now the Leaving Prairie Rose Reservation.” But it’s not the same Prairie Rose we started in; and most readers will never be the same either.

Want Sam’s life to stay the same, just with more money? Then donate to his Patreon!

Want Sam’s life to stay the same, just with more money? Then donate to his Patreon!