In the 1970s and ’80s, horror fiction came crawling back from the grave once again, as the unexpected success of novels like Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist fueled a wave of paperbacks that would, in turn, clear the playing field for the likes of Stephen King and Clive Barker to break into the mainstream. One of the running themes that tied this weird, diverse, salacious group of books together was the concept of the secret history, an undeniable product of the era of Vietnam and Watergate. Works both popular and marginal drew readers into sinister worlds buried beneath our own, from the mechanized chauvinistic dystopia of Stepford, Connecticut to the vampiric paradise of Anne Rice’s New Orleans to the towering evil of the Overlook Hotel, all born out of unease about an Americana that seemed to be crumbling with each passing day. Lovecraft’s Elder Gods no longer lay dead and dreaming at the bottom of the sea; they were built into our laws and charters, baked into the foundations of our modern world itself.

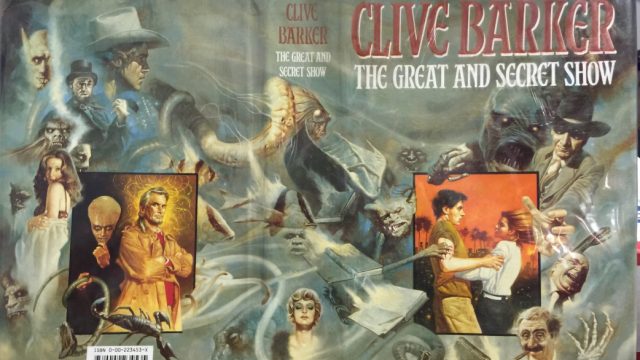

Clive Barker’s The Great and Secret Show was released near the end of this boom, as horror fiction was starting to slip back out of the spotlight once again. In a lot of ways, it reads like the natural endpoint of the genre’s fixation on secret histories, expanding the subgenre out as far as it can go into a strange, twisted American mythos. Its story begins in an Omaha dead letter office in 1969 (enjoy your parallels, Pynchon fans), but soon explodes outward as sociopathic post clerk Randolph Jaffe stumbles first onto the remnants of a dying secret society known as the Shoal, then out of the boundaries of our world itself and into Quiddity, the mystic “dream sea” that lives within mankind’s collective consciousness. Transformed beyond corporeal form by their voyage into Quiddity, Jaffe and his former collaborator-turned-nemesis Fletcher lay their sights on the California suburb of Palomo Grove as a battleground for control of the dream sea, drawing countless humans into the violence, romance, and mystery they leave in their wake.

If some of you are thinking that this story sounds oddly familiar, you’re right. In a modern sense, it’s hard to talk about The Great and Secret Show without bringing up David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: The Return, a series whose story seems to run in near-perfect narrative and thematic parallel to Barker’s novel. The bigger points of comparison are obvious – small-town melodrama juxtaposed with surreal cosmic skullduggery, numerous states-spanning story threads slowly drifting towards an inevitable collision, ancient evils seeking human form, and even working-class outsider perspective characters like reporter Nathan Grillo and FBI agent Dale Cooper. In their smaller points, too, Secret Show and The Return seem to be working in conjunction, even if their approaches don’t always line up; take, for example, both stories’ fascination with the atomic bomb. Both authors frame much of their supernatural mythos around the New Mexico atomic tests, but their approaches differ in ways that affect their thematic meaning. Lynch presents the Los Alamos test as a Pandora’s Box moment for America, turning the mushroom cloud into a slash through reality itself that rips open the veil between the Black Lodge and our world. Barker, meanwhile, transforms Trinity into a world crystallized in time, a secured and secretive loop in which imprisoned agents of the sinister Iad Uroboros plot their masters’ escape from Quiddity. Both fundamental traumas of the atomic age, both transformed into gateways between realities.

These parallels reach their most unavoidable in Secret Show’s second and The Return’s eighth parts, two eerie – and eerily similar – creation myths of American evil. Both Lynch and Frost’s “Part Eight” and Barker’s “The League of Virgins” center around unearthly pregnancies and the women forced to carry them; in “Part Eight”, Sarah Palmer’s body becomes a battleground where Laura Palmer’s pure, divine spirit clashes with an insectoid infection, while “The League of Virgins” follows the less-than-immaculate conceptions of Jaffe’s and Fletcher’s children and the subsequent collapse of their mother’s lives under closed-minded suburban scrutiny. Beneath the obvious comparisons, however, both artists quickly veer in different directions, particularly in their placement of the act of violation within their narratives. Lynch ends at the moment of infection without showing us its aftermath, as he’s already done that long ago – we know that what begins here will eventually culminate in Fire Walk With Me, in the tragic death of an innocent woman by her abusive father’s hand, in Pete Martell’s discovery of a body wrapped in plastic. Barker has no such precedent, and so he draws us step by step through the aftermath, through the judgement and shaming of Jaffe and Fletcher’s victims, through the way their lives are destroyed not by supernatural means but painfully human intolerance.

The most crucial difference, though, is the way Barker builds his story on myth and legend rather than the unrestrained dreamscapes of Lynch’s work, an aspect that brings into focus why his writings linger in the public consciousness after all these years. The horrific moment of conception in “The League of Virgins” comes as the waters the titular League linger in take on a life of their own, seizing and assaulting them in a way that mirrors Zeus’s assault of Danae as a shower of gold. Throughout The Great and Secret Show, this mythic aspect grows blurrier and more intriguing as the lines between ancient history and modern legend begin to collapse; modern messiahs explode into fire and light to share the gifts of their bodies; incomprehensible, Lovecraftian evils lurk amidst the islands of Quiddity; and the half-forgotten dead roam the streets of California, awaiting their chance to strike. In Barker’s eyes, myth is the invisible backbone that ties together all human history, eternally spreading and mutating across the centuries.

The Great and Secret Show’s release marks a major transformation in the history of genre fiction: the point at which secret histories make a full leap forward into the mythological, a transformation that will affect years of literature to come. Just as a line can be drawn from the early works of modern horror fiction to Barker’s novel, further lines can be drawn from that novel out into the burgeoning genre of urban fantasy, most notably into the works of Neil Gaiman. Stories like The Sandman and American Gods – and, naturally, Twin Peaks: The Return – carry on the ideas and themes that Barker helped solidify; in some greater sense, they’re all part of the same story, a history told in fantasies and dreams of a species struggling to grasp its own beautifully incomprehensible existence. In the end, it all flows back into the same sea, one we’ll never see for ourselves until the very end.