And if I show you my dark side,

Will you still hold me

Tonight?

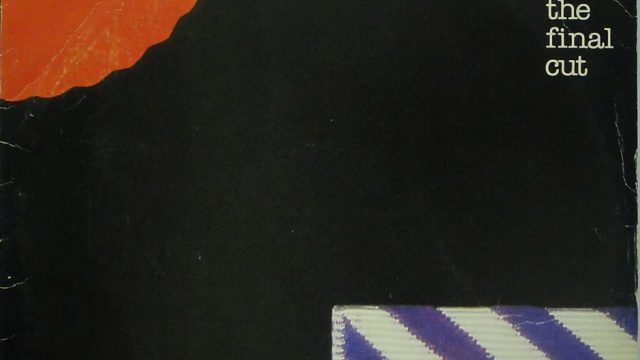

Few album titles have been as weighted with different meanings as The Final Cut. In the lyrics, it refers to the pain of cutting through your own defense mechanisms to connect to others, and of losing loved ones to war. But this is also a record where frontman Roger Waters took complete artistic control like a filmmaker given the right to final cut. And, in part because of that, it was the final cut he ever released as a member of Pink Floyd. He would go on to record solo albums, and David Gilmour and Nick Mason would use the band name without him, but by 1983 Waters was going and keyboardist Richard Wright was already gone. For the lineup that recorded some of the greatest albums of all time, this was the end. And while Waters’ ego trip destroyed the band, it’s hard to imagine this album coming together any other way. This story of the death of his father in World War II and the continuation of senseless conflict into the present may well be the most outspokenly political and deeply personal thing he ever recorded. If you’re being less generous, of course, you might prefer the words “preachy” and “self-indulgent.” Even Waters himself growled “not everything can be a fucking masterpiece,” but in this one case, the two of us will have to agree to disagree. The Final Cut, is, indeed, a masterpiece, stripping away the rock operatics of their previous release, The Wall, to create something every bit as moving, and at times, even more so. It clearly wasn’t for everyone, as some of the truly vicious contemporary reviews make clear, and I can’t say for sure how much my love of it is based on the affection Pink Floyd had earned through their earlier work. I can’t properly assess its value outside that context, but for those of us familiar with the band’s back catalog, it truly is a masterpiece, and a truly grand finale to the core lineup’s collaboration.

It opens with newscasts of Cold War paranoia before an organlike instrumental and muted brass set the solemn tone for the album. The fans who danced at the disco to “Another Brick in the Wall” are just going to have to wait their turn until well into side two. Waters asks, “Should we shout?/Should we scream?/Whatever happened/To the postwar dream?” As will become clear from the rest of the album, the answer is a very definite yes. This will be John Lennon politicizing delivered with a Yoko Ono primal scream. Technically, this is far from Waters’ best performance: it’s the kind of thing that gets you laughed out of voice lessons. But that was never the criterion he measured his singing by, and as far as emotion, this may well be his best work. “A lot of the aggravation [of the band’s break-up] came through in my performance, which, looking back, was really quite tortured,” he says, but “tortured” turned out to be the exact right approach to this material. Punk rock may have gained steam in part as a response to the grandiosity of the Floyd and their prog-rock contemporaries, but Waters’ raw, bleeding vocals here prove he could keep up with the best of them.

The opener transitions through industrial creaks and squeaks into the album’s highlight, “Your Possible Pasts.” Verses of pure poetry like “She stood in the doorway, the ghost of a smile/Haunting her face like a cheap hotel sign” are anchored by possibly the most heart-rending chorus in the Floyd catalog: “Don’t you remember me?/How we used to be?/Don’t you think we should be/Closer/Closer/Closer?” It’s a huge, heartfelt anthem that should be sung along with in a huge arena. And yet at the same time, it seems to demand an empty arena, with that sad isolated voice sitting in the shadows of an enormous, blank stage. Some of that’s due to Waters’ lyrics and inflection, but the echoing of that last word, “closer,” half reverb and half repetition, is the icing on the cake. The themes it develops make it an ideal companion piece to, or even final draft of, Pink Floyd’s earlier “Pigs on the Wing” from Animals. Both songs describe the horrific cruelty of the world and offer companionship as a possible solution. But where “Pigs on the Wing”’s folksy guitar backing was warm and intimate, “Possible Pasts” is cold and alone, a cry for help that may not be answered. Ironically, this magnum opus was one of David Gilmour’s sticking points on the record. Originally written for The Wall and part of The Final Cut’s protoypical stage, a Spare Bricks album to promote the movie version, Gilmour said of this and the other recycled tracks, “If these songs weren’t good enough for The Wall, why are they good enough now?” The answer’s simple: a song that’s not good enough for The Wall is still better than anything most artists could ever achieve. Gilmour’s antipathy to “Your Possible Pasts” is even more ironic when his screaming, thundering guitar line is among his finest achievements on a record that mostly pushed him to the background.

The next, brief track, “One of the Few,” re-emphasizes how much this album was the Roger Waters Show, with very little except for his reverberating vocals and a few sound effects. A World War II story scored to the ticking of a clock….could Christopher Nolan have been a fan? “When the Tigers Broke Free” gets to the traumatized heart of the album, the death of Waters’ father in the war. Scored by martial drums and a funereal chorale, mixed so it sounds like it might come from the other side, Waters details the story of his loss. With pointed parallels to the current Falkland Islands conflict, he tells of the hypocrisy of the powerful, when he recalls finding the personal note King George had sent his mother. With the same subtle, shocking venom that makes listeners wonder if they could heard right he deployed on The Wall’s “Mother” (“Hush my baby baby/Don’t you cry/Mother’s going to make all of your/Nightmares come true”), he pivots from mock-reverential to sincerely savage: “And my eyes still grow damp to remember/His/Majesty signed/With his own rubber stamp.” In the last verse, Waters’ voice almost breaks entirely as he puts his father’s death in poetic terms: “It was dark all around/There was frost in the ground/When the tigers broke free/And no one survived/From the Royal Fusiliers Company Z.” The music swells all through the song’s climax before suddenly vanishing, leaving nothing but Waters’ thundering words, “And that’s how the high command/Took my daddy/From me.”

That moment makes me wonder if I’m biased towards The Final Cut by my affection not for Pink Floyd, but another band entirely, because whether by influence or convergent evolution, it anticipates the work of Arcade Fire two decades later. Waters’ delivers that last line in a childlike Win Butler whimper that carries over, in more outwardly confident form, into the early bars of the next track, “The Hero’s Return.” The parallels to the later band in this song are almost eerie, with a bass and synth line straight out of Reflektor and keening synthesizers that sound uncannily like Regine Chassagne’s backing vocals. And while U2 were still in their angry young post-punk stage when The Final Cut dropped, you can hear echoes in “Return” of Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen’s rhythm section work for their later albums. The first lines of the song, “Jesus, Jesus,” sound like a desperate prayer paralleling the album’s opening words, “Tell me true/Tell me why/Was Jesus crucified?” Even as it becomes apparent that what we’re hearing is actually an officer cussing out his men, that impression lingers, and I don’t think it’s an accident. That transcendent longing continues to swim under the harsh exterior of the officer (sometimes interpreted as a return appearance by the schoolmaster from The Wall). He dreams that “even now part of me flies over/Dresden at angels one five,” and in a beautiful return to the themes of love and isolation from “Your Possible Pasts” sings,

Sweetheart sweetheart are you fast asleep? Good.

Cause that’s the only time that I can really speak to you.

And there is something that I’ve locked away

A memory that is too painful

To withstand the light of day.

That memory is “the gunners dying words on the intercom,” which we hear in full on the next track, and which may well haunt us just as much as it did him. The title and lyrics both suggest a Jacob’s Ladderish dream at the moment of death, as the gunner receives a vision of his own funeral in the album’s most poetic lyrics:

After the service, when you’re walking slowly to the car

And the silver in her hair shines in the cold November air

You hear the tolling bell

And touch the silk in your lapel

And as the tear drops rise to meet the comfort of the band

You take her frail hand

And hold on to the dream!

Musically, this moment is a mirror image of “When the Tigers Broke Free.” Where in that song the score built up to a climax before dropping out completely, this one drops a sudden, shocking climax in the middle of a soft, almost-whispered ballad. Where Waters’ voice was left alone on “Tigers,” here he screams in harmony with a saxophone. The gunner’s utopian dream is notable less for its optimism than the horror it stands against:

And what’s more,

No-one ever disappears.

You never hear

Their standard issue kicking in your door

You can relax

On both sides of the tracks

And maniacs

Don’t blow holes

In bandsmen by remote control

And everyone has recourse to the law.

And no-one kills the children anymore

And no one kills the children anymore.

The horror is emphasized by the implication that this dream is only a dream, and that these atrocities are still very much with us.

After the orchestral satire of British stocisim in “Paranoid Eyes,” Pink Floyd returns to the modern day with the one-two punch of “Get Your Filthy Hands Off My Desert” and “The Fletcher Memorial Home.” Named after his dead father, the home is called, in full, “The Fletcher Memorial Home for Incurable Tyrants and Kings.” As in Animals, Waters’ savage rage at the powerful coexists with pity and something like empathy as he almost sobs, “they can appear to themselves every day /On closed circuit T.V. /To make sure they’re still real. /It’s the only connection/They feel.” Even Animals couldn’t prepare listeners for the brutality of this song, though, as he fantasizes about inviting the world’s leaders to the Home’s grand opening (complete with announcements of the guest list) before asking, with silky menace, “Is everyone in?/Are you having/A nice/Time?/Now the final solution can be applied.”

The title track fits most comfortably into the narrative of The Wall, putting aside the subject of war to explore the themes of isolation and vulnerability quoted at the top of the article. After the soft tenderness of that song and the preceding “Southampton Dock,” the swaggering rocker, “Not Now, John” lands like a bombshell. This is all intentional, of course, since the track’s a parody of bread-and-circus jingoism, with David Gilmour (in his only vocal appearance) brushing aside Waters’ concerns because “Fuck all that, we’ve gotta get on with the show!” Waters’ experience adapting The Wall for Hollywood was obviously not pleasant: Gilmour’s character says, “Hollywood waits at the end of the rainbow/Who cares what it’s about as long as the kids go?” Industry and nationalism are also under fire: the causally racist narrator shouts “We’ve gotta compete with the wily Japanese” (which is queasily similar to the earlier, apparently sincere line “If it weren’t for the Nips/Being so good at building ships/The yards would still be open on the Clive”). Clanking and grinding gears play into the percussion track, most frighteningly when they complete the line “I used to read books but…” The lyrics portray modern life as an endless distraction from its own horror:

Can’t stop!

Lose job!

Mind gone!

Silicon!

What bomb?

Get away!

Pay day!

Make hay!

And the music emphasizes this point with a pitch-perfect parody of corporate pop, combining arena-rock guitars and backup singers vocalizing in the style David Bowie called “plastic soul,” their mock-gospel stylings hilariously incongruous for lines like “Fuck all that!”

The fun can’t last, of course, and both the album and the Gilmour/Waters collaboration end, fittingly enough, with the end of the world. Perhaps this closer left a bad last impression that would explain the album’s dubious reputation, since it features the records most embarrassing missteps, most notably the Elmo-pitched voice screaming “Daddy! Daddy!” as the bombs fall and a solo from the guy who played sax on Gerry Rafferty’s “Baker Street,” of all people. That said, “Two Suns in the Sunset” has plenty to recommend it. Like Bowie on “Space Oddity,” Pink Floyd combines futuristic subject matter with a low-tech acoustic accompaniment that creates an atmosphere of heavy melancholy. And while the end of life on earth might seem like a downer even by Pink Floyd standards, Waters still manages to find the beauty in it. There’s images like “My tears evaporate/Leaving only charcoal to defend” and the one that gives the song its name. But more than that, Waters finds elnlightenment in nuclear holocaust:

Finally I understand the feelings of the few.

Ashes and diamonds

Foe and friend

We were all equal in the end.

And finally, Waters draws the curtain on the band’s career with a dry, dark, perfectly British joke as the stodgy newscasters from the beginning put in one last appearance, making The Final Cut, like all their albums from Dark Side of the Moon on, an endless loop:

And now the weather. Tomorrow will be cloudy with scattered showers spreading from the east with an expected high of 4000 degrees Celsius.