Sam Cooke’s story is not unfamiliar if you follow early rock and roll: his father was a minister and he started singing gospel in the church before moving to rock. Cooke’s family was part of the Great Migration from the South to Chicago, and Cooke r grew up in a neighborhood dominated by economic success and black-owned business.

As a young teenager, Cooke began singing with a traveling gospel group as their gifted lead singer. “There were women who never thought about going to church who would show up because Sam was singing there,” Smokey Robinson remembered. (Dionne Warwick was one of them.)

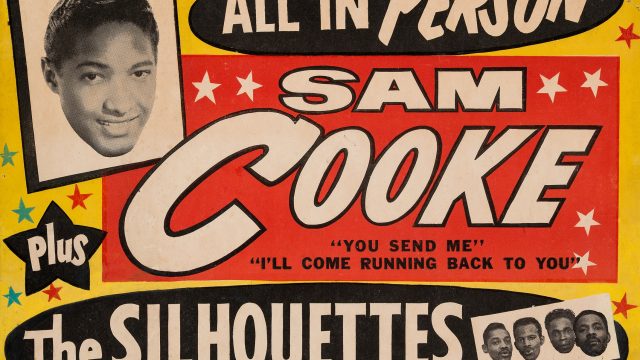

But pop stardom called, and Cooke soon embarked on a solo career, bringing his smooth, effortless vocals to songs both silly and sublime. Twistin’ the Night Away was released at the height of his career.

“Twistin’ the Night Away,” album and titular single, belonged effortlessly in the living room of any sixties family, black, white or otherwise; despite being a “twist record,” part of a fad of dozens of albums released in the wake of Chubby Checker’s “The Twist,” the album is still danceable and fresh fifty years later. It was accessible, mainstream and popular, and brilliantly crafted to be all three.

Cooke’s delivery is lively and intimate, inviting you to an exclusive party filled with interesting people, where you were an honored guest. He was your boyfriend or your very best friend, and he was always glad to see you.

But the friendly party host of “Twistin'” was only one aspect of Sam Cooke. Cooke was a songwriter—seven of the twelve tracks on “Twistin’ the Night Away” were written or co-written by Cooke himself, as were most of his thirty Top Ten hits. He co-founded a recording and publishing company with the goal of giving black artists a step up in the community (Bobby Womack, who played backup for Cooke, wrote the Rolling Stones’ first hit “It’s All Over Now” for his band the Valentinos on Cooke’s label, just one of the early successes in his long career).

Cooke was active in the Civil Rights movement and was listed in FBI surveillance records of Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X. Growing up in Chicago had given him little patience for the segregation he saw, especially in the southern “Chitlin Circuit.” In 1962, Bob Dylan released “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and Cooke incorporated it into his live act; it led to his releasing even more political songs, including the anthem “A Change Is Gonna Come” in 1964, a song that’s heard every Black History Month.

Of course Cooke was not without flaws. He was something of a womanizer, drank too much—especially after the death of his son Vincent in 1963—and the two women of color involved in his death accused him of sexual assault. (Family and friends strongly dispute this, and point to the FBI’s surveillance and contradictory reports around his death as good reason to be skeptical of the story. At this distance, I’m not in any position to make a judgement.)

Whatever demons Cooke battled, it’s impossible to see his death, only two years after “Twistin'” was released, as anything but a major loss to music, the Civil Rights movement, and African-American culture. Any platitudes about how “the music remains” seem hollow in the loss of a 33-year-old man who left a wife and two children behind.

But if you press the play button or drop the needle on “Twistin’ the Night Away,” all that fades, and you’re back at that party that never ends, hanging out with your very best friends and a half-dozen strangers you can’t wait to dance with.

Here’s a man in evenin’ clothes;

How he got here, I don’t know, but man, you oughta see him go

Twistin’ the night away…

Note: I can’t recommend the Netflix documentary ReMastered: The Two Killings of Sam Cooke, which was a huge help to this essay, highly enough, and would also recommend you check out Cooke’s live recordings, particularly Live at the Harlem Square Club, to see the looser, less structured performer he was outside the studio (especially when performing for a black audience).