Akira Kurosawa taught me about texture.

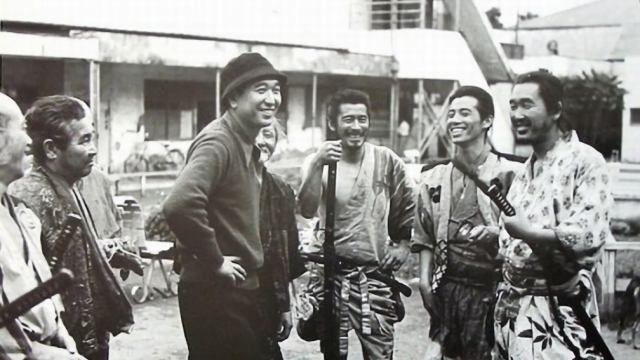

I’d watched plenty of black-and-white movies before and since, but there was something about the way Akira Kurosawa used light and dark to give his movies an almost-tangible feeling that’s always stuck with me. (Imagine how obnoxious I was when I first got a blu-ray player and watched a high-definition of Yojimbo for the first time.) The pattern of sunlight as it illuminates a field, the bright edge of a sword, the folds in a kimono; cinematographer Asakazu Nakai captures it all.

And Kurosawa and his co-writers, Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni, pay attention to the textures of everyday life, as well. For all the (well-earned) praise Seven Samurai receives for its excellent battle scenes and remarkable ensemble cast, the movie never forgets the village the ronin are working to protect, and the harvest the farmers are so desperate to hold on to. Takashi Shimura’s Kambei only decides to take the job of protecting the farmers after a laborer tells him that they are serving the ronin carefully prepared white rice while eating millet themselves. This scene, and the later moment when the ronin realize that the farmers have stockpiled armor and weapons from samurai they killed or let die, rip open the scars of the war-torn Sengoku period and the inordinate power samurai held over everyday citizens through an accident of birth. Even knowing the farmers are starving and desperate, it takes an impassioned speech from Toshiro Mifune’s Kikuchiyo to force them to recognize the harsh realities of a farmer’s life. Empathy comes, but only with a heavy dose of shame, and at the end of the day, the victory is more for the farmers than for the surviving ronin; and even with their newfound empathy, the survivors still haven’t quite grasped that for the farmers, this is a victory not at all guaranteed to last. Of course, by then Kikuchiyo isn’t there to remind them.

Kikuchiyo, of course, is the live wire and beating heart of Seven Samurai. It’s hard to believe that he wasn’t an integral part of the cast from the start; it’s not just the strength and energy of Mifune’s performance, it’s his ability to move between the farmers and ronin, while not really belonging to either, that gives Seven Samurai much of its narrative and emotional strength. A viewer doesn’t need to know what the Sengoku period was or what the social status was of a masterless samurai to understand why a group of starving farmers might not trust a group of out-of-work, aimless soldiers. But Seven Samurai makes sure to go beyond the surface of stereotype and shorthand to create and maintain characters who feel like they have lives well beyond what’s shown onscreen.

It’s no wonder that, for all the many riffs and homages and outright ripoffs of Seven Samurai, none of them quite manage to capture all the strengths of the three-hour original. I enjoyed both Magnificent Seven movies well enough, but they take more of the famous shots and much less of the spirit and the love of character and detail. The heroes are rarely allowed to be as raw and sometimes unlikable as the ronin of Seven Samurai.

I might go so far as to say they lack essential texture.