The eighties weren’t easy on New York City. The murder rate rose through the decade and peaked in 1990 at a staggering 2,245 (for comparison, last year’s rate was 290). By then, more than 5,000 people a year were dying of HIV/AIDS, a number that would continue to rise until the mid-nineties. Movies and TV depicted NYC as grimy, crime-ridden, and dark.

But not all of them had the same dark outlook. The “I Love New York” campaign pictured soaring skyscrapers and glamorous restaurants. Donald J. Trump, who had implicitly and explicitly connected himself with the city for most of his real estate career, published The Art of the Deal in 1987. The Cosby Show, an aspirational sitcom about an African-American family set in a Brooklyn Heights brownstone, ruled the ratings from its debut in 1985 until the end of the decade. As a culture, we’ve been picking over the contrast between picture-perfect shell and the rot beneath ever since.

Bret Easton Ellis’ novel American Psycho took a stab at it, and whether intentionally or not, bathed the artificiality of the decade in an ocean of gore and misogyny. Controversial among readers and critics, it took almost a decade for American Psycho to make the leap to movie theaters. Choosing a female director and writer was doubtless a major contributor to the movie’s critical success, but the perspective granted by time didn’t hurt either.

American Psycho tells you what kind of movie it is right in the credits. Over a bone-white (or perhaps eggshell) background, titles in a classic all-caps font play over drops of red liquid; the viewer quickly realizes that the liquid is raspberry sauce, and the large knife is cutting into that evening’s dessert for the bored yuppies soon to come into frame.

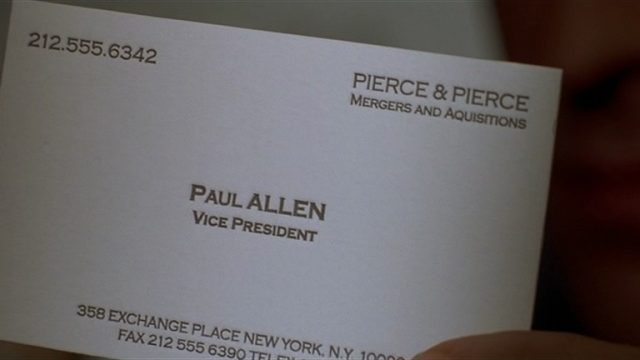

For a serious movie with the body count of a slasher film, American Psycho never loses its sense of play. The all-female writer-director team of Mary Herron and Guinevere Turner don’t shy away from the absurdity of a book whose lead character spends page after page talking about the awesomeness of Phil Collins and Huey Lewis and the News. Not a chance. They lean right in, from the over-the-top seriousness of the business card scene to the slapstick killing of Jared Leto to Turner herself appearing in one scene, flat-out-laughing at our protagonist. (Sure, she gets horribly murdered later, but it’s not like she’s alone in that.)

American Psycho starts with a wink and delights in its dark humor, but it’s neither heartless nor soulless; one prostitute Patrick Bateman toys with feels particularly human, and her fate, absurd as it is, stays with the viewer even as the movie’s plot veers further into the darkly ridiculous. (It’s the ordinary people, the ones without money or status, that Turner and Herron seem to care most about, from Willem Dafoe’s hard-to-read detective to the unfortunate homeless guy next to the ATM.) It spares its disdain for deserving targets; the men and women who partied while New York burned, their hair shellacked to perceived perfection, hiring little people as props for their theme parties and listening to the hollowest music they could find. (No disrespect to Whitney, Phil, or Huey.) No one cares about the gory murder in the apartment complex (the crack epidemic, the homeless, the sick and the dying). The owners and realtors slap a coat of bland paint on it and pretend it never happened.

There’s an intriguing argument floating around that American Psycho, the novel, is an extended HIV/AIDS metaphor incorporating Ellis’s self-loathing and internalized homophobia. The movie doesn’t have that kind of self-reflection; it’s a funhouse mirror of the culture as a whole rather than a fractured self-portrait. But in these times, when almost half the country voted for substance over style and the gap between rich and poor continues to widen, another look at the image in the mirror seems especially relevant.