Rosemary’s Baby starts out simply enough, though you can be forgiven for dreading what’s to come, despite the mundane introduction.

It begins with a soft-spoken, repetitive lullaby (sung by lead actor Mia Farrow), alongside composer Krzysztof Komeda’s piano melody before fading into the New York City skyline. The camera slowly completes a 180-degree pan from right to left while the credits roll, before gently tilting down diagonally and zooming out to reveal the apartment complex where the story is set: The Bramford.

Released in June of 1968, Rosemary’s Baby has endured, formally inducted into the Library of Congress as part of its National Film Registry in 2014. However, one needn’t look at that particular metric to judge its efficacy as an influential thriller. Take the opening shot, for instance, which borrows from Hitchcock’s Psycho and is borrowed again for Steven Soderbergh’s Side Effects. The iconic “Rosemary’s Lullaby,” might even be more influential, if you consider the number of horror movie trailers that use a similarly gentle melody before the smash cuts and jump scares begin.

Fortunately, Polanski is smarter than that, choosing to instead build tension through the slow, steady accumulation of details and events, building up to something truly frightening for our protagonist. This is largely by design, since the script, written by the director, exudes a fidelity to Ira Levin’s novel that most authors would kill for. According to Stephen King’s book, Danse Macabre, for example, Polanski phoned Levin while writing, wanting to know what issue of The New Yorker John Cassavetes’ character was looking at when he spotted an ad for men’s shirts. It turned out Levin had fabricated the ad, forcing the director to improvise.

In any case, Polanski might have been viewed as one of the best directors for this type of material, especially when one factors in his first three films. With Knife in the Water, Repulsion and Cul-de-Sac, he had certainly cultivated an ability to make the most of interiors and limited space. His movies kept characters locked in close quarters with a decaying, fragile mind, psychological gamesmanship and a preference for pessimistic endings.

As a result, the stars were perfectly aligned for Rosemary’s Baby to be Polanski’s American debut, coming off of The Fearless Vampire Killers. Robert Evans, the vice-president of production for Paramount Pictures, first purchased the rights after producer William Castle showed him proofs, well before Random House officially published it. Having seen Polanski’s prior works, he knew the director would be an excellent fit for the project, persuading him to come aboard by packaging the book alongside the script for Downhill Racer. Polanski, an avid ski buff, had expressed an interest in the movie, but changed course after reading the novel.

After establishing the apartment complex, the film introduces us to Rosemary and Guy Woodhouse (Farrow and Cassavetes), newlyweds getting a tour of the available apartment by the building manager, Mr. Nicklas (Elisha Cook Jr.) The rapport between Rosemary and Guy seems to be affectionate enough, with Guy providing plenty of verbal patter, calling himself a doctor after Nicklas asks about his profession. However, there’s also a slight undercurrent of bitterness to him, a semi-successful actor whose biggest claim to fame is a series of television plays and commercials, which he claims to do for the “artistic thrills,” in addition to the money.

We then get shown around the interior of the Bramford, which is clearly an older apartment building, with the original units being broken up “into fours, fives and sixes,” according to Nicklas. A maintenance man is drilling a new peephole into one apartment, and the floor has several tiles loose. With an old, crummy building like this, what’s to like? But one look at the actual unit available, and Rosemary is in love with the place.

Formerly rented by a Mrs. Gardenia, who had passed away in the hospital after lapsing into a coma, the apartment is hardly a loft or a studio. With a fully functioning chimney, kitchen and enough space to accommodate two bedrooms, it’s clear that it would be the perfect place for a young couple looking to build a family, especially since Rosemary plans to have children.

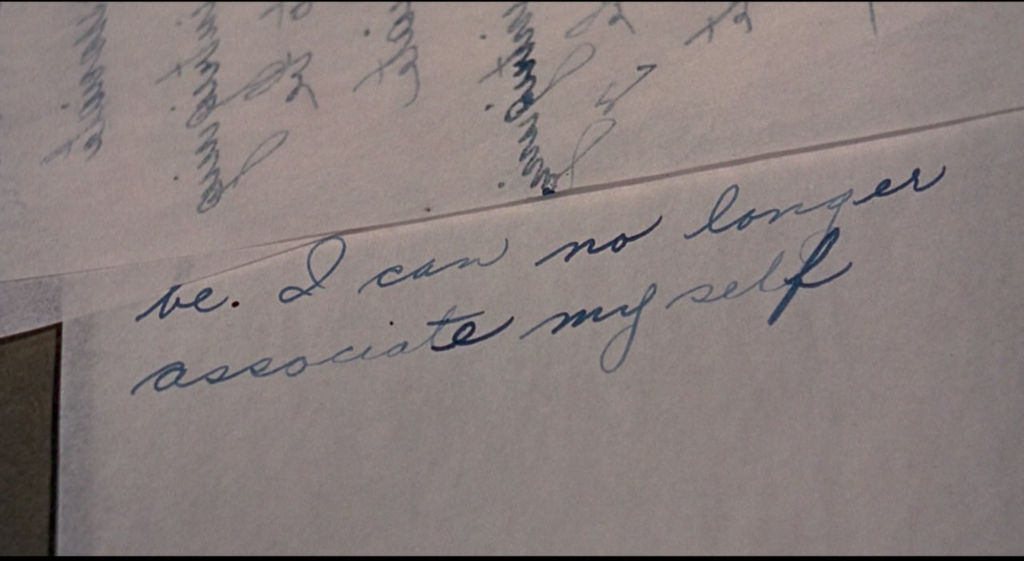

Eccentricities from the former occupant aside, which include inexplicably moving a bulky armoire to block a closet in addition to leaving behind an unusual note,

Rosemary loves it, pushing for Guy to acquire the lease. This allows the two of them to celebrate with their former landlord and close friend, Hutch (played by a lovingly paternal Maurice Evans).

It turns out the Bramford had a rather “unpleasant reputation around the turn-of-the-century,” according to Hutch, hosting some rather unsavory characters, including Adrian Marcato, a devout practitioner of witchcraft. The “Black Bramford,” as their friend explains it, also hosted the Trench Sisters, who were responsible for cooking and eating multiple children, including a blood relative, during the turn of the 20th Century. A dead infant was also found in the basement wrapped up in newspapers in 1959. However, much of the sordid history is dismissed. As Rosemary puts it, “awful things happen in every apartment house.”

She soon discovers how much of an understatement she’s made, as events slowly spiral out of control. For Rosemary, it proves especially damning, as almost anyone she views as an ally either keeps her in the dark or betrays her, as Charles Grodin’s Dr. Hill does near the end.

Getting asked to play a victim is almost never an easy sell, but Farrow makes it work here, pushing the character more towards a virginal innocent than an idiotic horror character. Even her hometown of Omaha conveys plenty. Without needing to reveal any specifics about her upbringing in Nebraska, we can immediately fill in the blanks: Here’s a young, wide-eyed ingénue, lacking the world-weary know-how and cynicism that a native New Yorker might bring to a similar situation.

Not that Rosemary has any reason to be distrustful. After all, Guy, despite his faults, clearly shows plenty of affection towards her, while their next-door neighbors are similarly welcoming. Played by Ruth Gordon (in an Academy Award-winning performance) and Sidney Blackmer, Minnie and Roman Castevet at first come across as basically decent, if a touch nosy and overly talkative. Also, like many New Yorkers, they aren’t very religious, arguing the Pope’s delayed visit to New York City is because of a lack of available publicity with the local papers on strike.

The theme of religion is a strong one in the film, given Rosemary’s Catholic upbringing. Polanski makes excellent use of this detail, with costume designer Anthea Sylbert dressing Farrow in virginal white or blue, with the notable exception of a red pantsuit and the red dress she wears at a party, symbolizing martyrdom as much as anything else.

Additional religious references abound, especially after Rosemary eats Minnie’s chocolate mousse, causing her to dream of sitting on the Kennedy family’s yacht, getting suspended beneath the Sistine Chapel murals and asking the Pope for forgiveness for not being able to see him during his visit to New York City.

However, it turns out God may not be able to help Rosemary, with the film driving this point home with that infamous Time magazine cover, “Is God Dead?” Eventually, she’s able to put the pieces together, realizing that the Castevets and the other elderly tenants of the Bramford aren’t just eccentric neighbors, but a coven of witches, eager to bring forth the Antichrist through Rosemary.

Here is where multiple viewings of this film can reveal certain obscure details, and you can begin to realize how deceiving their appearances are. How else to explain the note Mrs. Gardenia left behind, indirectly hinting at her role in something monstrous and profane? Or the Castevets pulling framed pictures off of their wall when the Woodhouses came over, to say nothing of the peculiarly similar coma Hutch succumbs to, without any clear reason except an eerie connection to Mrs. Gardenia’s? Similarly, the closet’s secret is soon revealed, showcasing how it is in fact a secret passage of sorts, allowing entry into the Castevets’ apartment and vice-versa.

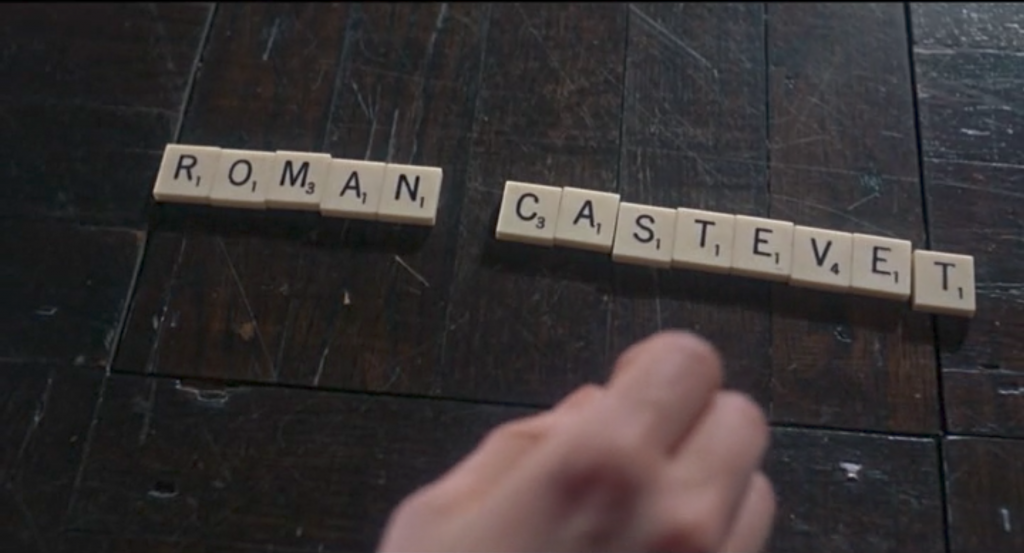

Of course, this film takes care to provide those moments of dawning horror for first-time viewers as well. Take for instance Guy’s change from loving (if self-centered) husband to knowing accomplice, for the sake of success in his career. Here, Cassavetes shows how his character is just as deceitful as the rest of the complex, albeit without the courage of convictions (watch how he slithers around the corner in the final scene, once Rosemary enters the Castevets’ apartment). There’s another excellent reveal when Rosemary takes out some Scrabble tiles, rearranging the letters to discover that Roman Castevet is actually Adrian Marcato’s son, Steven.

Rosemary’s Baby is typically viewed as a film about the horrors of pregnancy, which is a fair assertion, although there are other interpretations that might hold more weight. While pregnancy is certainly a strong theme, the terrifying realization about who the child is doesn’t occur until the end, and the fear never lies with it. Rosemary is far more worried about what the Bramford residents plan to do to the child after she gives birth.

Therefore, one could make the argument that the film is about the dangers of listening to an older generation and heeding their advice. For instance, the only allies she confides in without getting betrayed are her girlfriends of the same age, offering her advice to seek out another doctor at a party, one where “you need to be under 60 to get in.” This line is notable, considering how the film was released four years after Jack Weinberg’s comments about not trusting anyone over 30.

Aside from determining what this movie is about thematically, it offers plenty as a classic of the genre, capably tightening the screws on the audience and on Rosemary without the need for viscera, excessive musical stings or mood lighting. Perhaps the best way of understanding this film would be as a dark joke. After all, is there anyplace safer for Satan’s spawn than a Catholic womb, knowing the mother-to-be would never accept an abortion?