Few films have ever made the mundane yet universal act of studying so cinematically kinetic as The Paper Chase and few films are as relatable for those who have been severely tested by upper academia in life-defining ways.

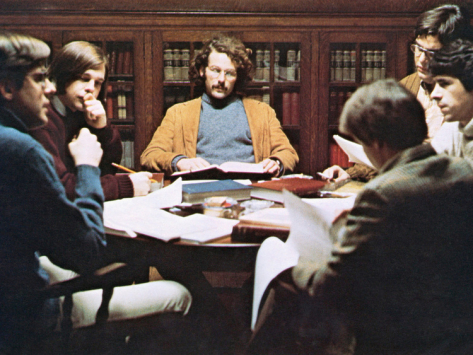

The Paper Chase stars Timothy Bottoms (yes, funny name, I know) as scholar James T. Hart, who is entering his first year at the Harvard School of Law. His two primary relationships involve an off-again on-again romance (Lindsay Wagner) and a worthy foil (John Houseman) in a stodgy professor whose rigidity and emotional blankness make him the stuff of legend. The big twist: The girlfriend is the professor’s daughter.When watching this for the first time, I was wary of how the film might devolve into some kind of triangular comedy (or melodrama, take your pick) of errors a la Three’s Company, but the romantic plot (or at least the tension) quickly dissipates. The love interest doesn’t particularly register and that plot quickly dissipates. I’ll even admit that five years after having watched the movie, I can hardly remember any details about those scenes and had a hard time remembering the actress who played her (full disclosure: I picked out the second name on IMDb. I’m not even 100% sure if’s Lindsay Wagner). One of the main reasons for the forgetfulness of the romance is that this is a plot devoid of conflict which seems entirely appropriate for this character arc: The film is largely between this man and the upper limits of his brain as opposed to an interpersonal conflict.

Even if you haven’t seen The Paper Chase, you may know that it won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor. The truism about the award is it rewards actors for playing extremes of human behavior and I’ve heard from others when discussing this movie that Houseman’s portrayal of Kingsfield is terrifying. A more apt description would be “hard to read.” His interactions with students are stoic and cryptic and in an atmosphere as intimidating as Harvard (I think using the actual title of the school as opposed to a fictional college title works well here), that can be terrifying. In this case, the student projects all the insecurities of whether he can live up to this prestigious institution onto Kingsfield.

Two of the most telling scenes revolve around the tension of Hart’s perceived relationship to Kingsfield who himself isn’t thinking much about it. When the two share an elevator, there’s a clear sense of tension in the claustrophobic space and the way the camera exploits that to show that, to Kingsfield this elevator ride is routine, but to Hart is an uncomfortable space. There’s also the eruption of Hart in Kingsfield’s classroom (the quote I actually included in my favorite film quotes of all time series):

The exchange is the definitive denouement of the Kingsfield-Hart conflict. Up until this point, the relationship has been undefined. Hart was bubbling with bottled-up frustration that he has directed at Kingsfield the irrational way any student hates his harder teacher. However, the codes of formality prohibited from expressing it. It is at this point that Hart conquers the intimidating image of Kingsfield in his head and says (though not politely) what he’s thinking. This resolves the Kingsfield-Hart relationship but not the whole movie, because, of course, the real battle is between Hart and the test.

But if The Paper Chase proves John Houseman’s skill as an actor, his acting career can still best be described as his third-greatest contribution to the arts. His greatest career was producing stage plays on Broadway beginning in 1929 as as means of surviving the stock market crash. It was in 1934 that he became “obsessed” (wikipedia’s words, not mine) with the idea that a 20-year old actor from a play at Cornell University (I believe that’s what’s meant by a Cornell production) would be the only person qualified to play the lead of his latest play. That 20-year old was Orson Welles and the two became collaborators. Houseman also produced the radio play “War of the Worlds” that scared the shit out of New Jersey when people thought it was real.

Ironically, whereas Citizen Kane marked the birth of many careers (Rob Wise edited the film; Agnes Moorehead went on to earn four Oscar nominations; Gregg Toland was the preeminent cinematographer of his day, etc.), it ended the collaboration of Welles and Houseman. It was mostly the controversy over who wrote the play with Houseman taking the side of Herman Mankewicz.

Want more Orrin? Check out his website on sophomorecritic.blogspot.com or follow him on twitter at @okonh0wp