“Most people stop at the Z…but not me!”

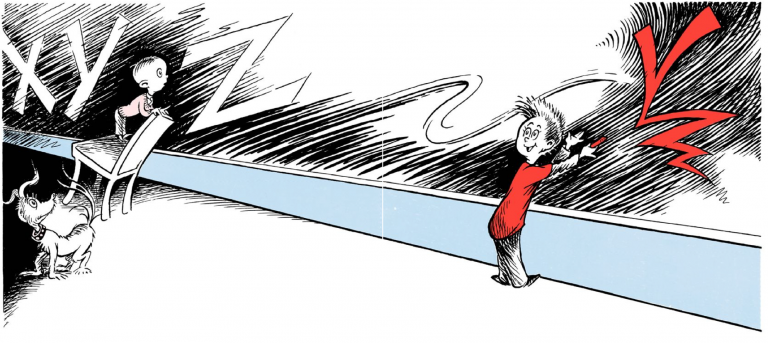

If there’s ever been a more succinct summary of what makes Dr. Seuss and all visionary artists great (the real ones, not the “visionary directors” in Hollywood marketing), I’ve yet to hear it. Two years before he turned the easy-reader upside-down with The Cat in the Hat, he did the same to thr alphabet book with this. Even in 1955, the form was old enough to be ripe for deconstruction, and Seuss’s personal stamp was recognizable enough to make him the man for the job. Letter-animal, letter-animal “The A is for Ape. And the B is for Bear,” on and on, until we eventually get to Z and hopefully the little ankle-biters don’t make us start over from the beginning. This being Dr. Seuss, he replaces the alphabet with a new alien language that leads to the kind of creatures that no other artist could ever create. This may seem a little harsh on the classic alphabet-book format. After all, it’s a valuable part of teaching children to read. And that’s true, but On Beyond Zebra! teaches children less tangible, but perhaps even more valuable lessons. The younger child (with the wonderfully Seussian name Conrad Cornelius O’Donald O’Dell) is right on the path to dull conformity with his miniature cardigan and necktie. His teachers have presented to him a small, cramped universe: “And now I know everything anyone knows/From beginning to end. From the start to the close./Because Z is as far as the alphabet goes.” The older boy, with his baggy clothes and wild shock of hair where Conrad’s is parted neatly down the middle (possibly Marco, who “told such outlandish tales” in Seuss’s very first children’s book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street?) is a Cat-in-the-Hat-style disruptor. With that lively curlicue leading into letter YUZZ, he explodes Conrad’s mundane, complacent world into the visionary realm.

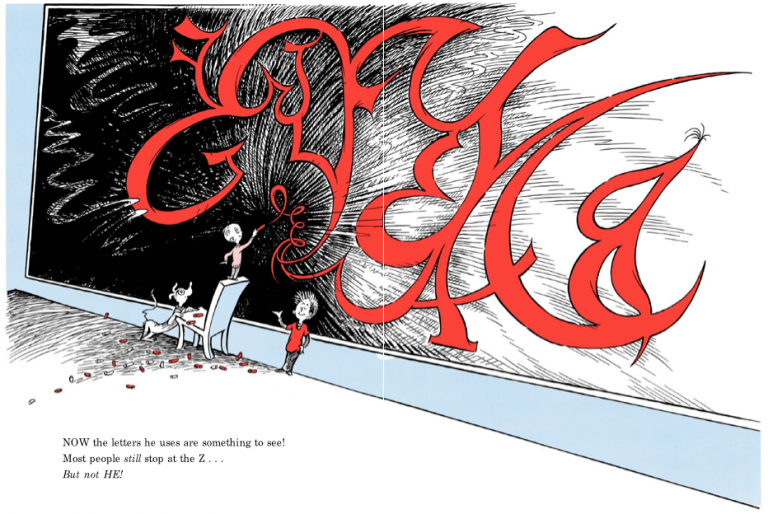

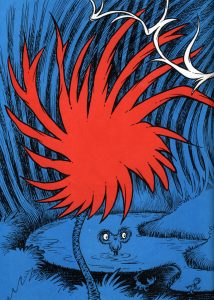

“Explodes” is a metaphor Dr. Seuss himself might have had in mind, actually: check out the final page where Conrad writes up his own letter, with a starburst emanating from the chalk and squiggles like smoke plumes floating up from the left edge.

The artwork in this introduction is also a great example of Seuss turning his limitations into advantages. For budget reasons, his early books were only printed in two colors, red and blue, so he makes the setting a staid black-and-white except for Marco’s bold red shirt and the red chalk he uses to open up the world beyond zebra, with paler pink accents on Conrad’s cardigan and his dog’s collar. He maximizes his limited palette elsewhere too, using deep blue to suggest a lot of shadowy atmosphere in his minimalist art of the “underground grotto in Gekko” or the “swampf and swumpf” where they find the Humpf-Humpf-a-Dumpfer.

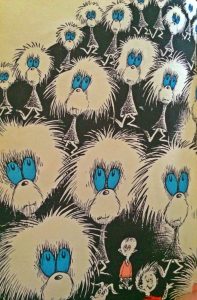

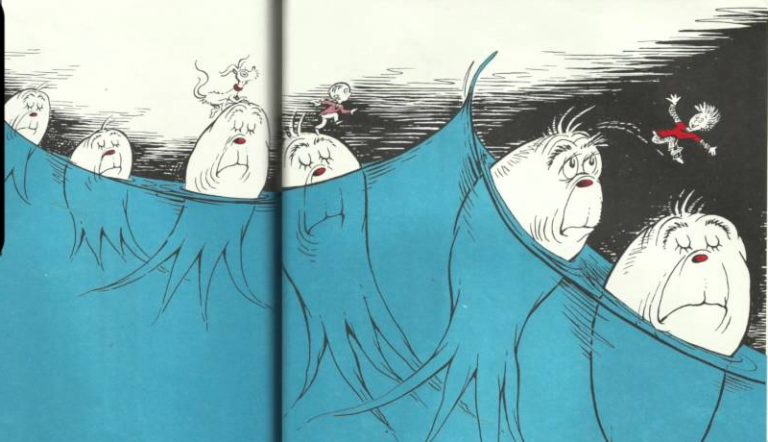

And while he uses bold splashes of red, blue, and pink throughout the book to suggest a brighter, more colorful atmosphere than he can actually show, for the somber page of “Jogg-oons, who doodle along, crooning very sad tunes” he hides his lead characters’ colorful clothes in the bottom corner for a drawing dominated instead by dark blues and shadowy cross-hatching.

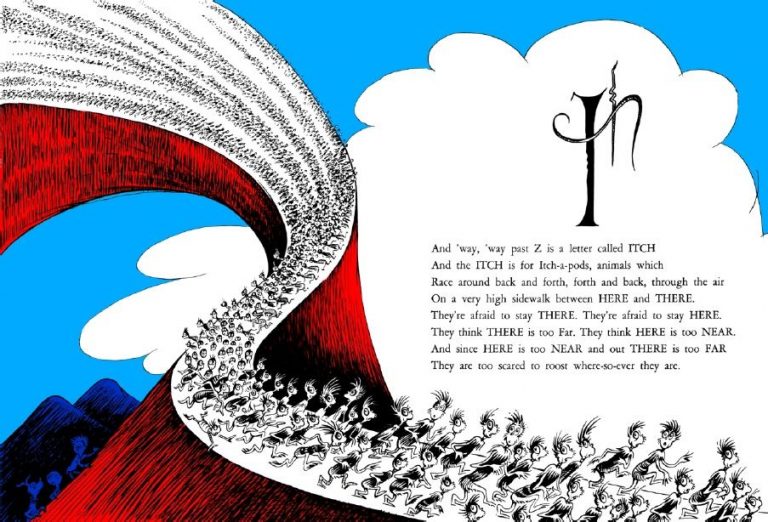

All this analytical ponderousness is a bit out of character for an artist as light-heartedly unpretentious as Dr. Seuss, I’ll admit. The man himself was highly skeptical of modern art: after pulling off a hoax where he sold abstract art as “Escorobus,” he took a cynical view of the medium: it “amde me suspect that a lot of modern art is malarkey…If I can do it myself, it can’t be any good.” The fact is, he was too modest. On Beyond Zebra! is as fine a work of abstract expressionism as any in the snooty galleries where he peddled his fakes. If Marco’s breathless narration fills the story with explorative energy, the art does even more, built around wild curves and arabesques that keep pushing across each page and onto the next. In other words, it demands readers keep moving, but also rewards closer examination. Just look at the illustration of the Nutches, where Marco improbably drapes himself between two clawlike zigzag mountains.

The landscapes seem to move with the characters, like those abstract pyramidlike waves that rise in M-shapes and then fall again in a mirror image of Marco’s arc as he jumps from one Floob-Boober-Bab-Boober-Bub to another. (And it’s fortunate that Dr. Seuss wrote in such a way that you can’t quote him with any more seriousness than he warrants. Read that last sentence with a straight face, I dare you.)

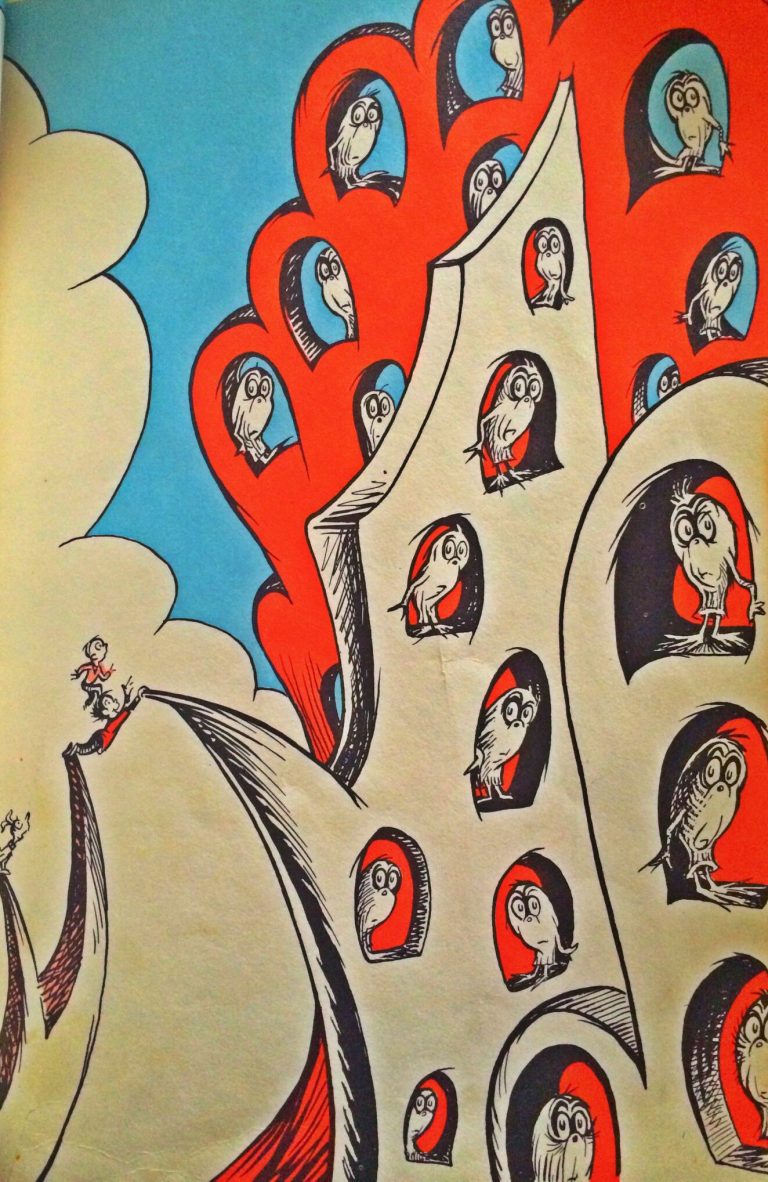

Or just try and trace all the abstract, intersecting arches of the grotto, or the snakey underwater tree that Marco and Conrad balance on to get a look at the Qunadary. (This was, in fact, what some of the kids did with Dr. Seuss books during my time as a preschool teacher.)

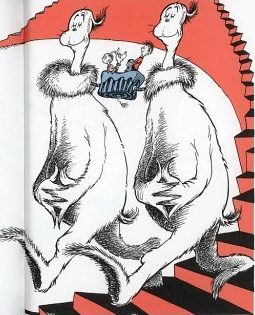

The settings reinforce the book’s message that the world is full of unlimited possibility. There’s a lot of stairways and walkways to nowhere, some of them, like the one the Itch-a-Pods run back and forth along, with, as they say, no visible means of support.

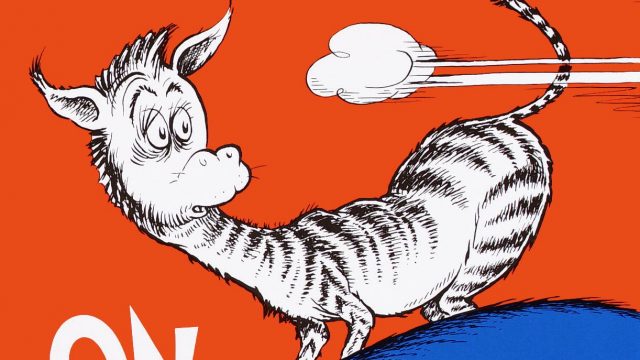

The cover shows nothing but the dust some unknown object kicked up as it ran past a bewildered zebra.

Seuss captures the High-Gargel-Orum just as they’re about to literally step off the page, and some of the Jogg-Oons are already partway there: one of them only has the tops of its eyes poking into the frame. The Umbus seems to stretch, hoof after hoof, udder after udder, into infinity.

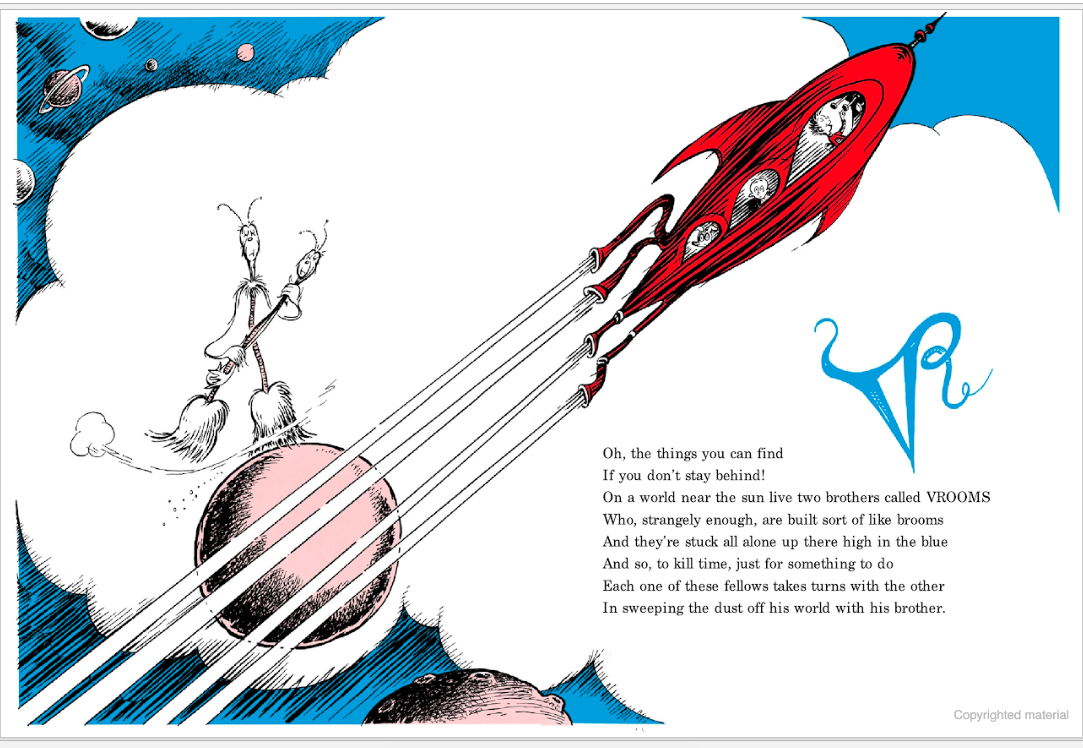

Marco’s crazy, mismatched rocket with buttons and exhaust pipes sticking out every which way streaks in from the corner of the page and off past it, with its nose extending beyond the blue block that represents the sky, as if it’s exiting reality altogether. To infinity and beyond, as another children’s character would put it. Or maybe it was just a mistake, there’s always that.

Marco’s crazy, mismatched rocket with buttons and exhaust pipes sticking out every which way streaks in from the corner of the page and off past it, with its nose extending beyond the blue block that represents the sky, as if it’s exiting reality altogether. To infinity and beyond, as another children’s character would put it. Or maybe it was just a mistake, there’s always that.

But the greatest message of potential to Seuss’s young readers is right at the end. After listing all the new letters the books has introduced and the new creatures they go with, the last page is just the fluid, mutant letter Conrad came up with, and the message, “…what do YOU think we should call this one, anyhow?” Like all good teachers, Dr. Seuss gives children the tools to make the most of their lives, then lets them loose to see what they can do with them.