Someone once told me the very beginning is a very good place to start, and you can’t start any earlier with Oh, the Thinks You Can Think! than the title. There it is, right there on the cover before you can even open the book. It sounds like a celebratory exclamation, and also like a challenge. And that’s what it is. But is it directed at the readers or Dr. Seuss himself?

Oh, the Thinks You Can Think! is somewhere in between those Dr. Seuss books like One Fish, Two Fish or Hop on Pop that are just one darned thing after another connected only by the occasional returning phrase or character, and those others like Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book or On Beyond Zebra! that set up a loose plot that’s really just an excuse for Seuss to draw up another cabinet of curiosities. There’s no story or characters here, but there’s a thematic connection beyond “stuff Dr. Seuss thought was cool,” a celebration of the imagination. Yes, so is every Dr. Seuss book, but here he comes out and says it, encouraging his large audience of small people to think of the craziest shit they can. (I’m sure that’s exactly the language he’d use if he were here now.) It’s like an instruction manual to imagining: Dr. Seuss will get the kids started, and now they can follow on from there.

But the title challenge is really to Dr. Seuss himself, and it seems to have given him new life. It’s easy to forget this since he hit the peak of his popularity in the ‘50s, but as Charles Cohen points out in his essential biography The Seuss, the Whole Seuss, and Nothing But the Seuss, that marks the exact midpoint of his career. By 1975, Seuss was entering his seventies (he was born almost at the beginning of the century, which is nice when you want to calculate how old he was at any given time). Age was clearly beginning to take a toll on his art. His illustrations were never as technically accomplished or lusciously detailed as peers like N.C. Wyeth or Chris Van Allsburg, but they had a rich, fluid line that became flatter and shakier as Seuss’s career went on.

And while his Beginner Books gave him his greatest success, they rarely inspired his best work. The art and stories had to be simpler to appeal to these small readers — most Beginner Book illustrations don’t have Seuss’s trademark byzantine backgrounds, or any at all, just blank voids — and their small hands meant he had to work on a smaller canvas. He almost seems bored with some of these projects, like the previous year’s There’s a Wocket in My Pocket. It’s a perfect setup for a classic Seuss bestiary, but the various household critters are all minor variations on a few templates, less unique or imaginative than any of the nameless “things” that “go to the right” in Oh, the Thinks You Can Think!

These limitations could be frustrating — Seuss loved to tell an almost-certainly embellished story about the long gestation process of the first Beginner Book, The Cat in the Hat. He got to work on a story about a bird only to find out “bird” wasn’t on the approved vocabulary list, so he started again with a story about a “wing thing.”

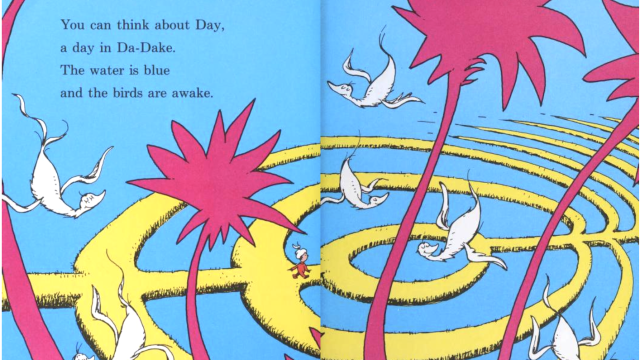

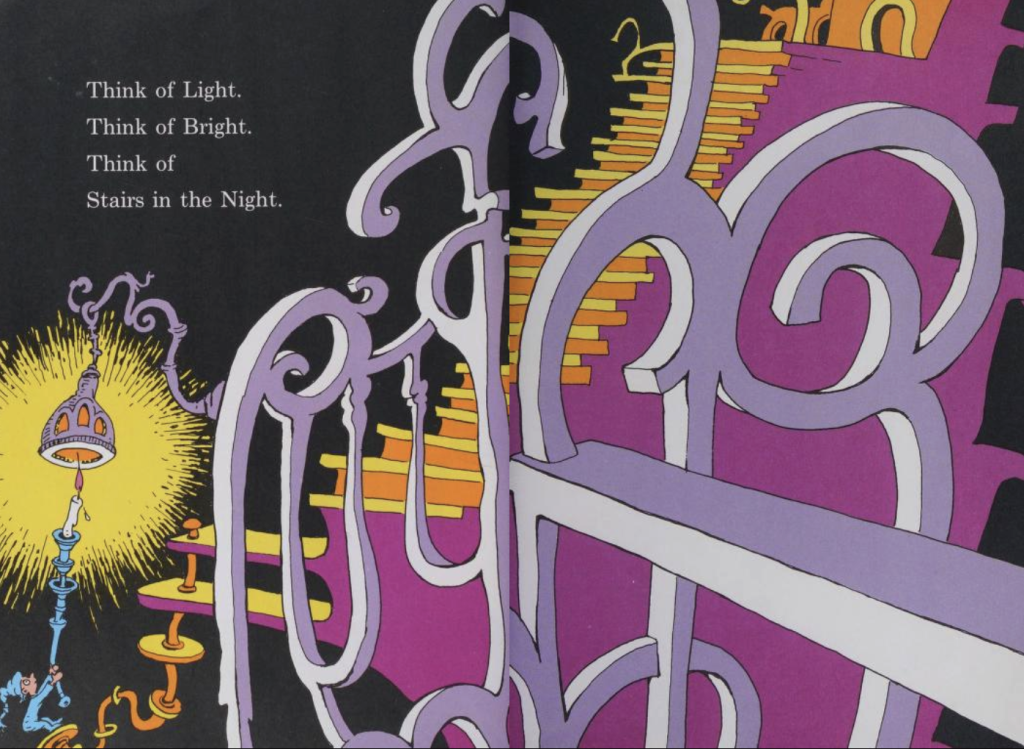

But those same limitations could be inspiring. There’s hardly any text in Oh, the Thinks You Can Think! and while Seuss did the whole thing himself, it’s illuminating to think of the process as a kind of collaboration. The less Seuss the author gave Seuss the artist to work with, the more he did with it. “Think of light/think of bright/think of stairs in the night” is about the most mundane text in Seuss the author’s whole catalog. But Seuss the artist goes buckwild with it, imagining a structurally intricate and impossible staircase floating in the blackness, framed by an incredible series of arabesques that could be a gate or a grate or God only knows what. It’s almost totally abstract, and yet vividly concrete thanks to a few simple perspective tricks.

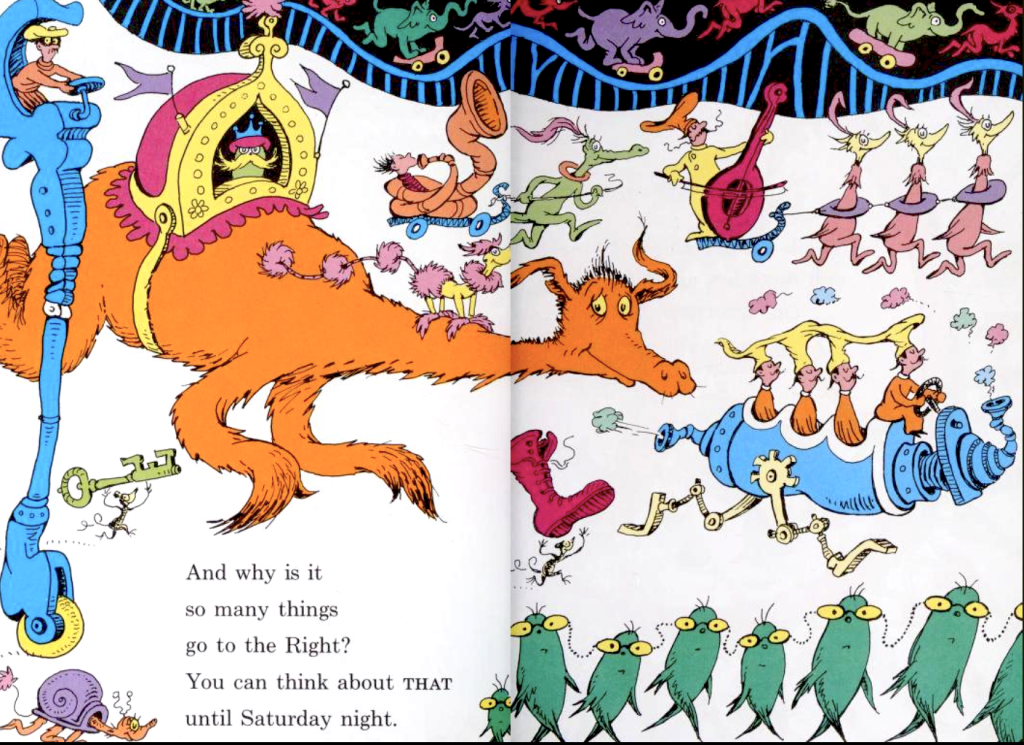

On a later page, Seuss the author asks, “Why is it so many things always go to the right?” without any indication of what those “things” might be. Seuss the artist’s answer includes, but is not limited to, mice carrying keys and boots several times their size for reasons known only to them, a masked man piloting some type of elaborate unicycle, a chorus line of fishy green things connected by their glasses chains, four men even more improbably connected by a single hat driving some impossible contraption with jointed legs instead of wheels and exhaust pipes belching out candy-colored smoke at both ends, a cello (?) player with a mustache that makes Kenneth Branagh as Hercule Poirot look downright subdued being towed by a yoke of Sneetchlike birds, and some kind of green rajah Lorax riding on a horse-dog-camel thing in an elaborately decorated litter.

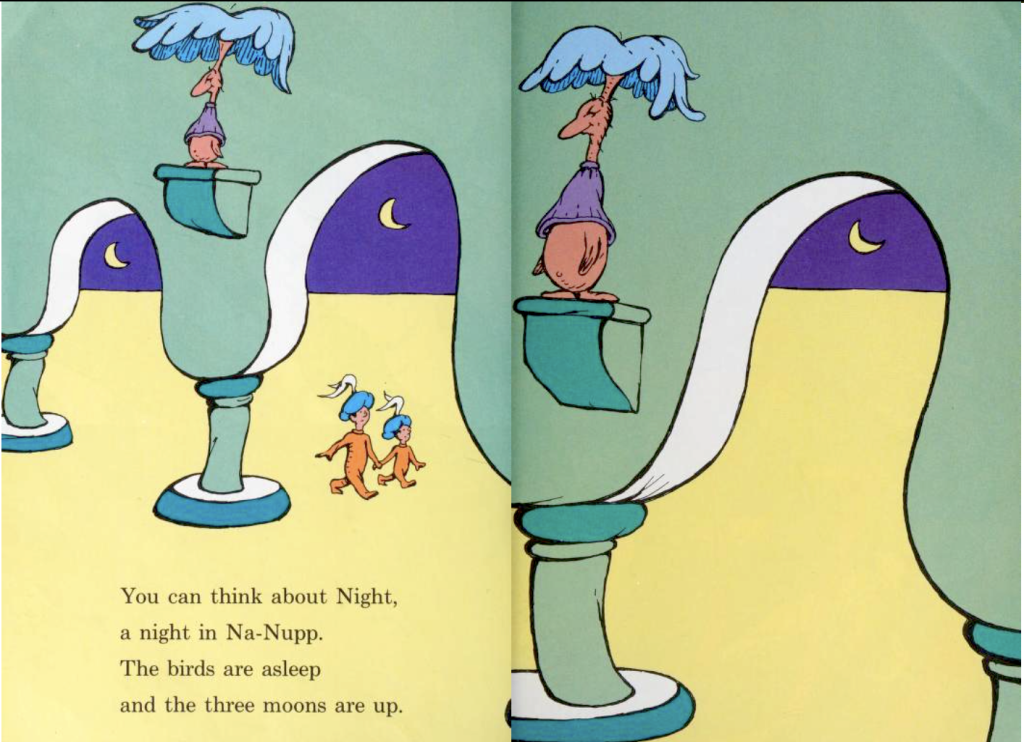

“You think about Night/A night in Na-Nupp/The birds are asleep/And the three moons are up” is already an evocative image. But it’s hard to imagine anyone but Dr. Seuss interpreting those nondescript birds as bizarre potbellied critters with huge umbrellas of feathers growing out of their heads in little crop-top sweaters that their wings somehow don’t seem to fit into.

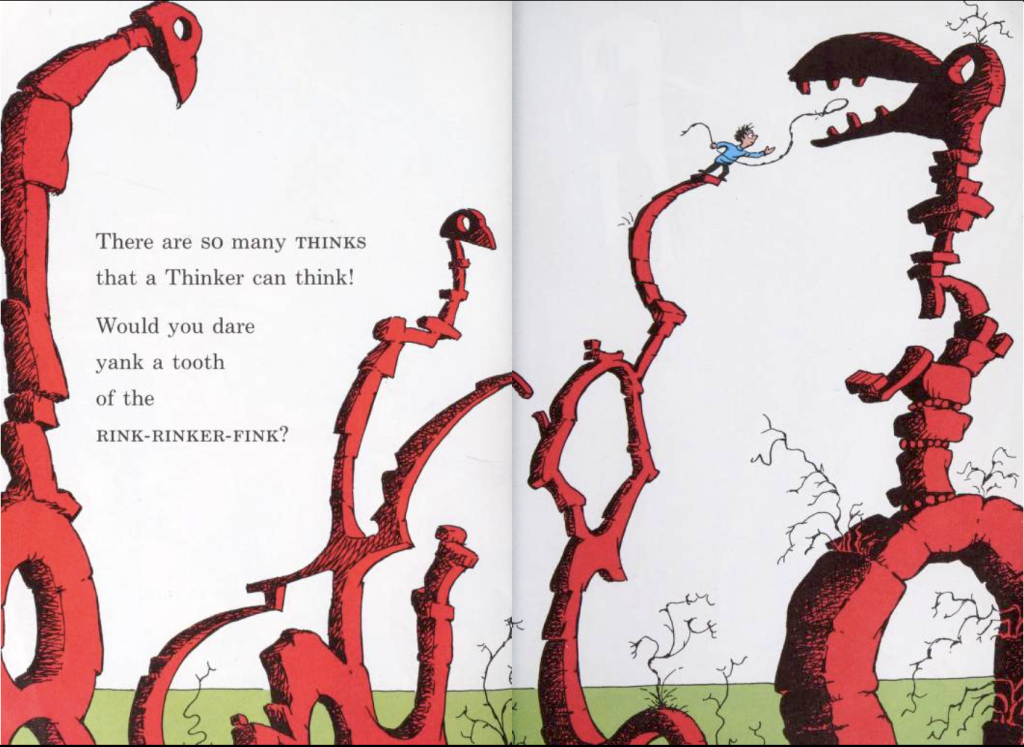

Dr. Seuss is a bit of an outlier in beloved children’s artists since, as our own Drunk Napoleon has pointed out, the best way to make sure kids remember you is to scare the shit out of them. Dr. Seuss rarely dipped his toe into horror territory, but two consecutive spreads here show he was more than capable of it. The first asks, “Would you dare yank a tooth of the RINK-RINKER-FINK?” What the fink is a Rink-Rinker-Fink? The illustration doesn’t offer any concrete answers, but that’s what makes it so compellingly unsettling.

Dr. Seuss combines things kids are already vaguely uncomfortable with — stone faces that could be dragons or gargoyles or vultures waiting for you to drop over dead; rickety, overgrown structures their parents would tell them to keep away from — but that doesn’t quite account for the image’s power. Either way, the kid in the illustration is obviously in much greater danger than just that precarious precipice he’s standing on. Even the playful squiggles of the weeds hang heavy with menace.

Anyone who’s ever said anything about horror could tell you that since we fear the unknown, the less we know about the source of our fear, the more effective it is. Dr. Seuss clearly understood this principle as well as Lovecraft or any of his imitators. And it’s a uniquely childish type of fear, too. To Dr. Seuss’s target audience, everything is unknown, and anything could be deadly.

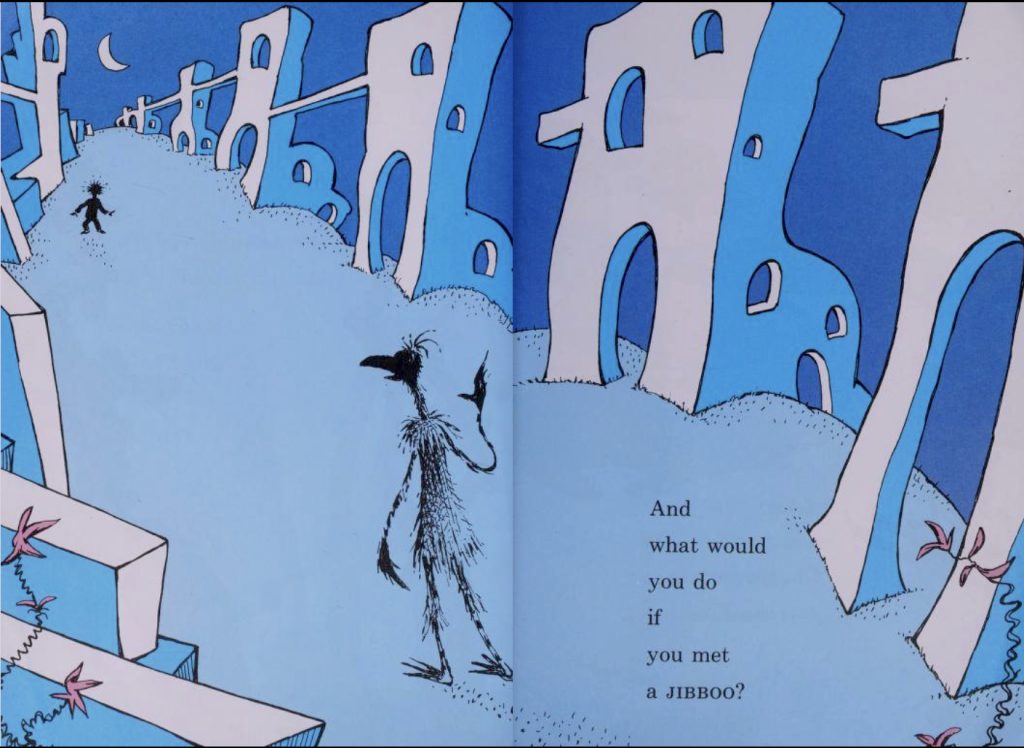

The next page is even more remarkable. The text is as sparse as anything Seuss ever wrote: “And what would you do if you met a JIBBOO?” On paper, the Jibboo shouldn’t be scary. It’s a lanky goony-bird of a thing with arms like frayed pipe cleaners. But the way Dr. Seuss renders that goofy design turns it into something else, silhouetted with the only illumination coming from a few thin, scratchy lines, its expression unreadable. More importantly, there’s the layout of the image, with the reader surrogate as a small figure in a dark, desolate landscape, flanked by buildings I can only describe as Seussian Brutalism.

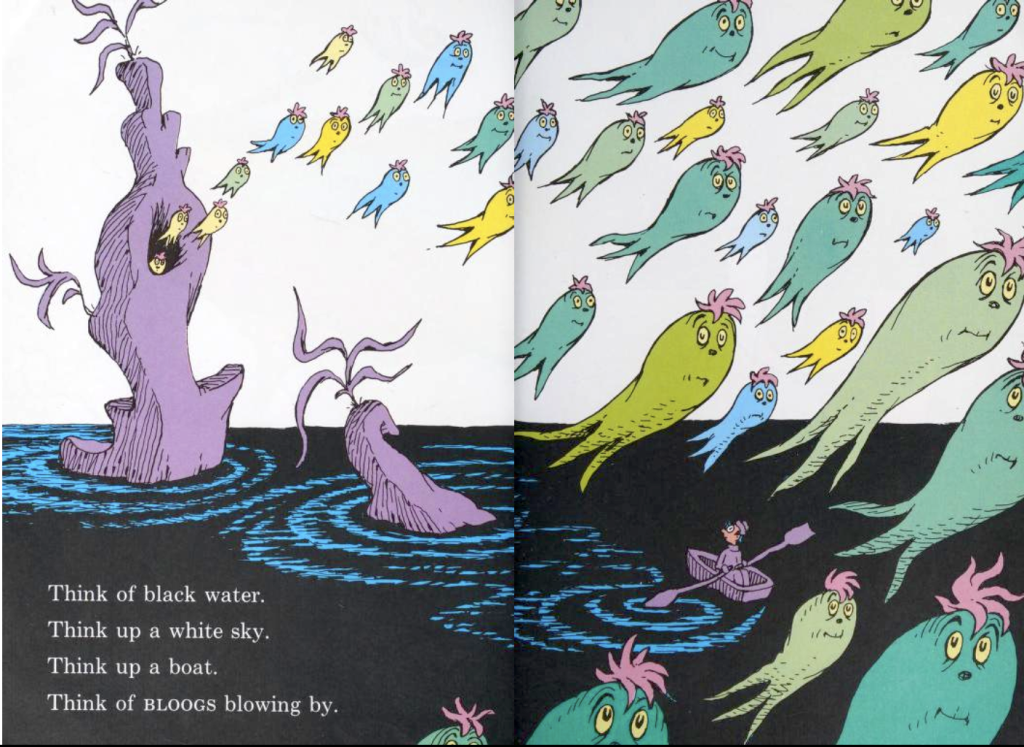

That same mingling of silliness and spookiness gets a milder workout earlier in the book, which introduces “Bloogs.” They’re goofy-looking balloon-shaped critters with tufts of hot pink hair. And yet, there’s something ghostly about the way they float in the “white sky” above “the black water,” which establishes a moody color palette that extends to the lonely rocks jutting out of the sea.

But let’s get back to that childish acceptance of the unknown. Kids are the perfect audience for Seuss’s brand of nonsense. Sure, words like “Zong” and “Vipper” are strange, but so are most words to anyone with a preschool vocabulary. Seuss wasn’t even the first to realize this — he’s the heir to a long line of children’s absurdism from Lewis Carroll through Edward Lear through Carl Sandburg.

A personal story might help clarify the phenomenon. One of our favorite family Seusses was You’re Only Old Once (originally a gift to the grandparents, who didn’t much appreciate the gesture). The elderly protagonist wanders through all the indignities of a trip to the hospital, including one doctor who quizzes him on a long list of allergens including, “Corn on the cob. Also buffalo grease/And how you react when you’re stared at by geese.” And every single one of the hundreds of times we read this book, my little sister would ask, “What’s stairdabygeeze?” This became family lore for years until my sister finally revealed how traumatic it was, because my parents, caught up in their adult sense of the world, couldn’t conceive of it as a genuine question and just laughed without answering. (And with that out in the open, it got to be funny again.)

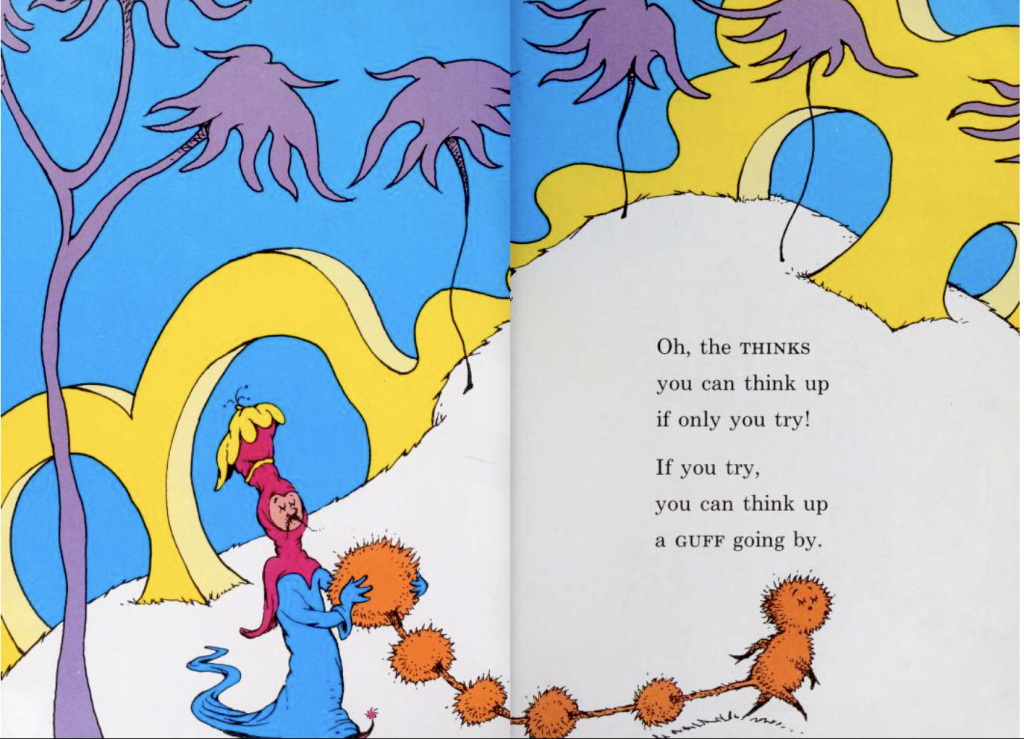

And it’s a fair question. To a toddler, what’s the difference between “stared-at-by-geese” and “Grinch” or “Voom” or “Oobleck?” Seuss also took advantage of this fact by coming up with alternate definitions for existing words. A “Guff” is a creature with a puffball-covered tail so long he needs an attendant to carry it, which Seuss illustrates with his trademark skill at hilariously incongruous looks of exaggerated dignity.

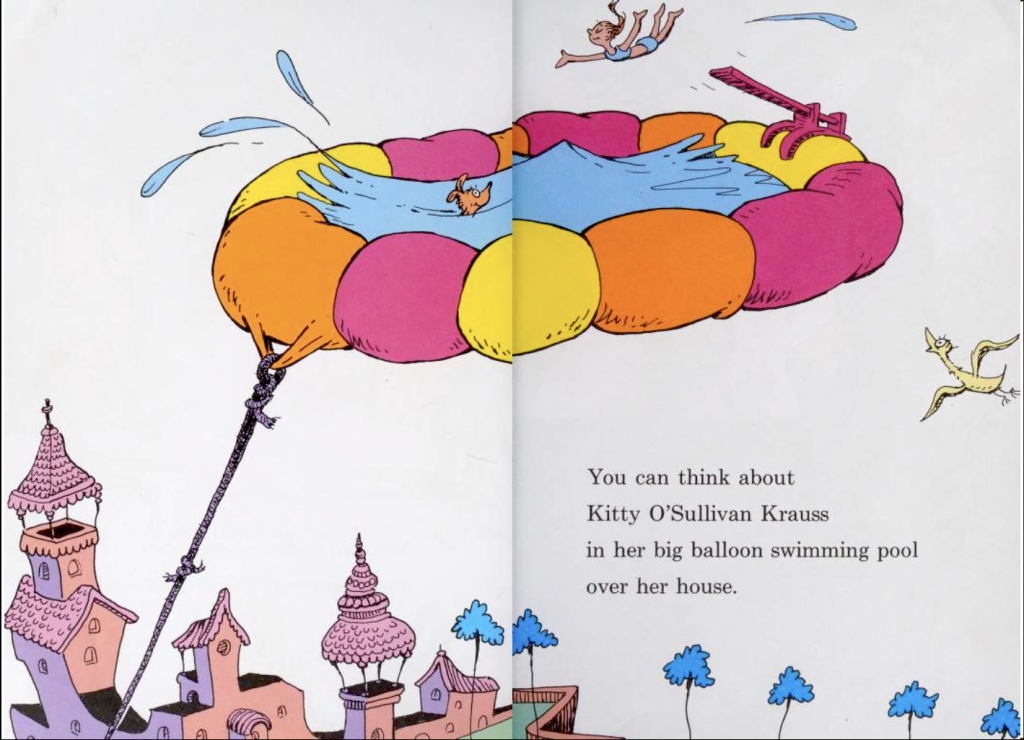

Of course, Seuss isn’t above the usual childhood wish-fulfillment even if he couldn’t resist injecting with his singular sensibility. Who wouldn’t want to be Kitty O’Sullivan Krause with a big balloon swimming pool over her house? And who but Seuss the author could come up with an image like that? And who but Seuss the artist could have rendered it with so much perversely logic-defying believability?