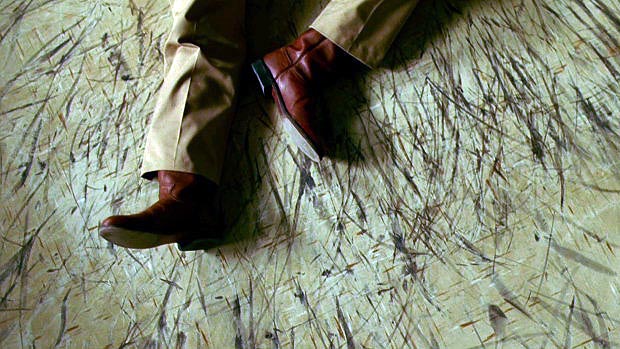

No Country for Old Men was the ninth picture Roger Deakins shot for the Coen Brothers, and it shows the strengths of their long-term collaboration: it’s not only beautifully shot, it’s shot in a way that draws out and maximizes the creative forces behind the film. Deakins chooses a vivid color palette here—the burnt orange and stark biscuit sand and blue sky of the desert are maybe the most memorable, but there are also the warm sepias of Llewelyn’s cheap hotel rooms and the cooler grays and blues that trail along after Carson Wells. He also fills the film with perfectly, poetically composed shots: Chigurh and Ed Tom looking at their reflections in the blank TV screen or white dust spraying in an arc against a dark blue sky as the car chasing Llewelyn fishtails to a stop. The colors and compositions feel straight out of late-period Cormac McCarthy, a mythic scope executed with sparseness and restraint.

Late-period McCarthy toned down his Blood Meridian-era streak of Western Gothic grotesquerie and the bizarre, but that’s something the Coen Brothers—partly via Deakins—restore to brilliant effect. The movie luxuriates in its humor and the specificity of its milieu. It captures the sweat on a glass milk bottle, the light-footed way horses walk around a crime scene in the middle of the desert, the kind of socks sold at a country-western boot store, the chicken feathers in the bed of a truck, and the prices of cheap hotel rooms; it makes room for instantly recognizable country characters like the gas station attendant (mild and terrified) and the trailer park manager (firmly committed to her position). The effect is that the mythic coexists with a very specific microcosm.

That’s something the Coens have always understood, but it’s an approach that’s maybe even more successful here than it is in O Brother, Where Art Thou. That may be because of how easily No Country for Old Men transitions between its various milieus and how it understands which characters carry their worlds with them and which are defined by what’s around them. And it occasionally surprises you with that understanding.

Despite the fact that Llewelyn Moss (Joshn Brolin) and Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) are the protagonists, the active characters to whom Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) is the largest and most present threat, they are not his opposites: they’re all, paradoxically, cut from the same cloth. They’re all invested in what Chigurh calls a rule, some kind of governing certainty. Ed Tom has his belief in justice (steady) and goodness (fraying). Llewelyn places his faith in his own competence, and he’s almost right to; he has a true gift for practical solutions whether they involve tentpoles and coat-hangers or scrounging up a jacket and a bottle of booze to mask how battered he is as he passes into Mexico. He’s undone partly by an act of kindness—returning to the shootout scene with a gallon jug of water for a dying man—and then entirely by him underestimating the sheer otherness of Chigurh, not by any failure of resourcefulness. The crime he’s punished for is not stealing the money, really—it’s not having the moral imagination to understand that there are parts of the world that are not, and never will be, comprehensible. That hamstrings him when he comes up against Chigurh, because Chigurh is just as capable but has a wider range of possibilities, a fair number of which are completely invisible to someone like Llewelyn. Partly, No Country for Old Men feels like an inverse version of the famous exchange in Manhunter:

“I know I’m not smarter than you.”

“Then how did you catch me?”

“You had disadvantages.”

“What disadvantages?”

“You’re insane.”

Notice the tapering-down of that dialogue as it goes on, with Will and Hannibal boiling their conflict down, bit by bit, to a core objection. Will Graham wins in Manhunter, because Mann is a procedural realist. Llewelyn Moss loses in No Country for Old Men, because the Coens are myth-makers. Their films exist in a world of signs and wonders, and failure to recognize those wonders, dark or bright, is not a kind of sanity that will save you.

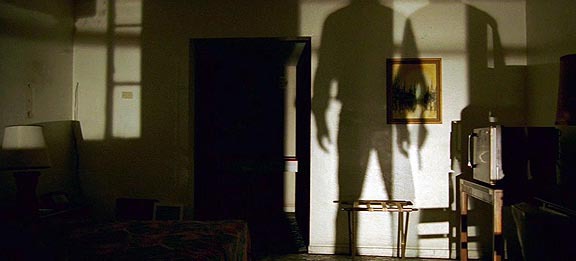

Ed Tom Bell can recognize the natural force of Chigurh (“I don’t want to push my chips forward and go out and meet something I don’t understand”), but he mistakes its source. He think Chigurh’s existence is because times have changed, and it takes Ellis, the true old man in the story, and one who exists in his country just fine, in the end, to correct him: “What you got ain’t nothin’ new. This country’s hard on people.” Ed Tom makes the opposite of Llewelyn’s mistake, essentially, and tries to go up against Chigurh almost on moral terms alone. Llewelyn fights with his body and mind; Ed Tom fights with his soul. They both lose, but Ed Tom’s mistake is more survivable.

Carson Wells (Woody Harrelson) and Carla Jean Moss (Kelly Macdonald) are Chigurh’s real opposite numbers, and they’re the only ones who compromise him—not physically but existentially. Carson Wells is one of Harrelson’s best performances, restrained and funny, with an upper-echelon professionalism that marks him as an outsider: when we find out he’s a retired Army colonel, it feels like the final puzzle piece clicking into place. In some ways, Wells is ineffectual—he doesn’t succeed in retrieving the money, and he gets killed by Chigurh—but his dignity is ultimately unshakable, which means he doesn’t feel ineffectual. He persuades Llewelyn to talk to him. When he recognizes that his situation with Chigurh has become hopeless, he’s calm even in his fear, and he sees Chigurh with a hardened clarity:

“Let me ask you something. If the rule you followed led you to this, of what use was the rule?”

“Do you have any idea how crazy you are?”

“You mean the nature of this conversation?”

“I mean the nature of you.”

He’s the first person Chigurh goes up against who has some idea of who Chigurh really is, and it lends their confrontation a haunting significance. It feels like preparation for Chigurh’s scene with Carla Jean, especially in terms of how Wells refuses to entertain Chigurh’s philosophies.

And he’s right to do so. If there’s one thing No Country for Old Men seems to insist, it’s that it doesn’t matter what rule you follow—if you even follow any at all. Tragedy, death, and chance are, and always have been, ready to descend on all of us. Nothing can save you from the inevitable costs of being human. Of, as Ed Tom says, saying “I’ll live in this world.”

That’s something Chigurh only has to face after his meeting with Carla Jean. He’s following his rule by being there, and she recognizes it immediately. Like Wells, she’s terrified, but she doesn’t become someone else in her terror. She’s a young woman scarred by too much grief, with an incredible innocence radiating out of her all the same, and she doesn’t concede any of that to Chigurh. (“I ain’t got the money. What little I had is long gone, and there’s bills aplenty to pay yet. I buried my mother today. Ain’t paid for that neither.”) She remains fragile without actually breaking.

And she forces Chigurh, gradually, to come into her world, because she won’t enter his. At first, he’s completely comfortable, musing on how people always tell him he doesn’t have to do this, and when he offers to trade the certainty of her death for the uncertainty of the coin flip, it’s with a kind of condescension. And it’s a mistake, because unlike the gas station attendant, Carla Jean doesn’t waffle and ask for clarification. She refuses:

“This is the best I can do. Call it.”

“I knowed you was crazy when I saw you sitting here. I knowed exactly what was in store for me.”

“Call it.”

“No. I ain’t gonna call it.”

“Call it.”

“The coin don’t have no say. It’s just you.”

“Well, I got here the same way the coin did.”

In the novel, Carla Jean’s refusal is, in the end, only temporary. The Coens cut away discreetly before her death, before we can ever know whether or not she folds, but I have always believed in my heart that she doesn’t. She forces Chigurh to ignore his own bullshit philosophical alibi, forces him to take an action without a justification (if he had, in his mind, the right to kill her because of Llewelyn, he lost it the second he agreed to the coin toss). She understands his insistence on the coin toss better than he understands her refusal of it, and that comprehension makes him small enough to be vulnerable to the same forces of chance and fate that he’s always considered himself to be a part of. It’s only after this that he can fall victim to the same accidents as everyone else and really, truly be hurt.

So in the end, the earthly collapses because of a lack of understanding of the mythic, and the mythic collapses because of a lack of understanding of the earthly—or at least of a myth other than itself. We end not with Chigurh, limping along the road, but with Ed Tom Bell, finally retired and at home with his wife. We end with dreams, borne of specific people and circumstances but lifted up above them into something larger, older, and archetypal. The dreams are how the worlds and philosophies in No Country for Old Men are finally, briefly unified. To misquote Joan Didion, we tell ourselves dreams in order to live.

And then we wake up.