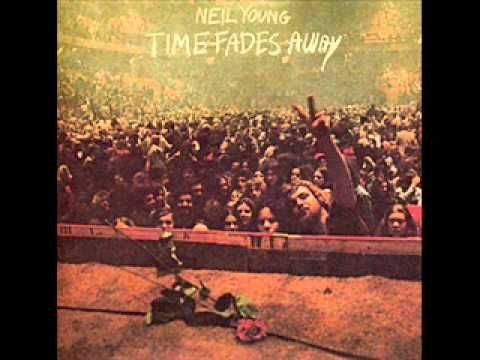

Time Fades Away is a lesson in how almost everything going wrong can produce a staggeringly powerful work of art. And it started from, at the time, Neil Young’s biggest success, Harvest (1972), a record front-loaded with laid-back country-rock hits, interspersed with darker tunes about heroin addiction and racism.

To capitalize on the mainstream popularity of Harvest, Young was booked on a three-month tour of playing arena-sized shows. Meanwhile, the only guy who could play guitar and sing with Young as if the two were blood brothers, Danny Whitten, had become a flat-out junkie. Seemingly unaware of Whitten’s dire condition, Young hired him for the touring band, but he showed up at the rehearsals in no way capable of handling the assignment.

Making the most fateful decision that shaped Time Fades Away, Young sent Whitten home. That night Whitten died of a drug overdose. Plans to record an album of new songs before the tour fell through in the wake of his death. At the last minute, Young got a mobile recording truck to get the new songs down on tape while being played in front of audiences expecting to hear the hits off of his last record.

One can only imagine what audiences thought when they heard “L.A.” A lumbering guitar riff introduces a scene of surreal apocalypse (“An ocean full of trees”). In the chorus, the mood becomes introspective, Jack Nitzsche sounding melancholy piano notes as if surveying the wreckage, Ben Keith soaring on pedal-steel guitar before Young brings it down to tell us everybody wants to attend the end-of-the-world party: “Don’t you wish that you could be here too?” Keith plays a tagline. After the verse and chorus repeats, the song ends. The audience applauds on cue–exactly the canned response Young didn’t want.

“L.A.,” which ranks with Young’s finest songs, is the center of Time Fades Away. The center doesn’t exactly hold, however, which is perhaps why Young, from a professional viewpoint, calls the record his “least favorite.” Long out of print, Young finally made it available again in 2016, after fans kept bugging him. Among them were R.E.M., paying it homage by recording New Adventures in Hi-Fi (1996) in a similar manner.

Making Time Fades Away was, on a number of levels, an unforgettable ordeal for Young and his band. Kenny Buttrey was a big-time Nashville drummer used to a comfortable studio environment. Because Buttrey had played on Harvest, Young thought he could play shows with him, even if it required Buttrey’s being lavishly compensated for studio sessions missed while being out on the road. When the rest of the band found out, they all demanded more money.

Young raised their pay, which made them, in his mind, his hired hands. He stayed in separate hotel suites, aloof and alone. What started as a band ritual of getting high on their chartered plane escalated into drinking and drugging to handle the boredom before shows. When they took the stage, they had to keep up with Young, whose penchant for getting wasted on tequila pushed him further out on the edge. They didn’t know whether to play loose or tight. Either way, Young would be unhappy, and he’d lecture them after shows.

Young was also displeased with his guitar sound. Having made the curious choice of using a Gibson Flying V rather than his trusty 1953 Gibson Les Paul, which was being repaired, he got a darker, thinner tone that washed out in the mix, despite his obsessively adjusting mics and amps. Driven to distraction by Young’s demands, the sound crew had to deal with two more guitars played by David Crosby and Graham Nash, who were recruited to help when Young later on the tour blew out his voice. Known for his arrogance, Crosby refused to turn down his guitar.

By the time the songs for Time Fades Away were recorded, Buttrey was gone, unable to keep playing as loudly as Young wanted. He was replaced by a more conventional rock drummer.

Young rasps, “Fourteen junkies, too weak to work,” that opens the first song, the title track. It sounds like a manic version of the country-rock the audiences came to hear. After antagonizing them, we hear Young at the piano, playing solo. “Journey Through the Past” is about being homesick, worrying that his lover will still be there when he gets back. In its bare sketched-out form, the song, with a forthright honesty, documents the tensions of touring, echoed by the two other solo piano-vocal performances, “Love In Mind” and “The Bridge” on the record.

“This will be kind of experimental,” someone (likely Crosby) mumbles into the mic. The band lurches into the demented blues of “Yonder Stands the Sinner.” Young sounds close to gone as he narrates a fractured tale of Southern Gothic psychodrama. They all may have been confused and exhausted, playing to a largely indifferent crowd, but, at the very least, they’re getting into the song.

Written the day after Whitten’s death, “Don’t Be Denied,” is one of the finest songs in the so-called “confessional” genre. Shot through with survivor’s guilt, it painfully surveys the distance between dreaming of being a star, and the emptiness of being one. Young, refusing to turn back, lets loose with his anger at the record-company execs who sent him out on this nightmarish tour while he’s feeling emotionally vulnerable: “I’m a pauper in a naked disguise/A millionaire through a business man’s eyes.”

The album closer, “Last Dance,” is a weary attempt to make an arena-friendly rock number that turns into an endurance test. A simple, sledgehammer guitar riff punctuates Young’s thoughts about working a 9-to-5 job. Nitzsche and Keith both pick up on his downer mood, layering blue notes on top of each other. Young realizes, finally, it’s another trap, shouting “No, no, no,” over a static one-chord vamp. He wants out, but where to go? The song thuds to a halt, without an answer.

After the tour, Young figured out that he needed to play smaller shows. His next records were intended to leave anyone in the dust who had jumped on the Harvest bandwagon. He wrote in the liner notes of Decade (1977), a handpicked compilation of his songs, that the hit songs on Harvest “put me in the middle of the road. Traveling there soon became a bore so I headed for the ditch.”

What is now known as “the ditch trilogy” is Time Fades Away, On the Beach (1974), and Tonight’s the Night (1975). While On the Beach and Tonight’s the Night are two of Young’s best studio works (and I hope to write about them in the future), no record captures, in the rawest form, the existential angst of a 70s rock tour quite like Time Fades Away.

For more about the Time Fades Away experience, see Jimmy McDonough, Shakey: Neil Young’s Biography (2002)