The other day, I had to stop myself when I realized I was arguing with someone who wasn’t there over something that hadn’t happened. This compulsion to make up stories or create dramas and cast them with versions of people we know is all too human. If you’re lucky, you can be a writer and get paid for it, though perhaps there should be quotation marks around “lucky.”

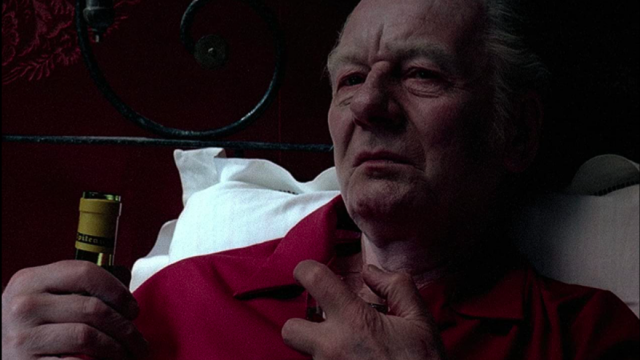

In Providence, a collaboration between French director Alain Resnais and British writer David Mercer, we witness writer Clive Langham (John Gielgud)’s drunk night of the soul,. Early on, Langham spills a glass of wine in his bedroom and we hear Gielgud’s “Damn, damn, damn” on the soundtrack. We’ll hear his voice throughout the film, sometimes feeding lines to the characters, sometimes dubbed over the other actors. He comments on the action and people onscreen as if this was Mystery Science Theater 3000. It slowly becomes apparent that what we see are Langham’s drunken fantasies mixed with rough ideas for a novel he is writing. Mercer’s script makes it easy to follow even while you’re confused. It’s a stream of consciousness, in which you slowly figure out the story of the author’s life and then find out you’re completely wrong.

After the spilled wine in the bedroom, the action moves to a courtroom. David Warner plays a soldier named Woodford who is on trial for his mercy killing of a sick old man while on maneuvers in the woods. Woodford is being questioned by Langham’s son Claude, a prosecuting attorney played by Dirk Bogarde at his most supercilious and sarcastic. Woodford testifies that not only was the old man sick but he seemed to be changing into some kind of animal…like a werewolf.

“Sick old man” refers to Langham himself. He is suffering from bowel cancer, the effects of which Gielgud describes in graphic detail. Soon, Langham is crafting a story in which Claude’s wife Sonia, (Ellen Burstyn), tries to have an affair with Woodford. This changes the movie into a Pinter-esque portrait of an unhappy long-term marriage in which the partners say things like “I don’t think I’ve ever been a ‘problem,’ have I, Claude? Problems have a way of acquiring status in a relationship, you see,” and “[We live] in a state of unacknowledged mutual exhaustion, behind which we scream silently.” It was lines like this and the arch way they’re played (Bogarde in particular savors every word and chews every scene) that led critics like Pauline Kael to sniff, “Some people have a surprising tolerance for this sort of thing.” Yes, because it’s a parody, just as the “seduction” in Last Year at Marienbad can be seen as a parody of the games that men and women play while the style of that film plays with cinematic codes and techniques.

Resnais has always had this playful side. In films like Hiroshima Mon Amour, Night and Fog, and Je T’aime, Je T’aime, he plays with cinematic form but treats the content (respectively, war atrocities, the holocaust, and suicidal depression) with the gravity they deserve. But Providence shows his silly side, albeit with a straight face. It’s almost like a Monty Python movie at times. Woodford mentions he has a brother (“a famous footballer”) and sure enough, this brother materializes in shorts and a soccer shirt to interrupt scenes or run through the background. Shortly after Sonia discusses the antipathy between Claude and his father Langham, there’s this exchange:

Sonia: How strange…

Woodford: So’s this.

Sonia: What?

Woodford (slightly panicked): I’ve got an erection.

Sonia: Ooo, so you have. Is it urgent?

Woodford: It isn’t mine!

Providence’s DNA can be found in a lot of later work, including Dennis Potter’s The Singing Detective, Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch and eXistenZ, Greenaway’s Prospero’s Books and Charlie Kaufman’s work. Watching it, I can’t help but think of David Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. Lynch has named Resnais as one of his favorite directors, but I haven’t been able to find any mention that he has seen Providence. Both films are structured in two sections with characters in the first part based on characters in the second. The first part of Mulholland Dr. shows an exciting, idealized Hollywood, a dreamworld that soon gives way to the ending’s more depressing reality. In Providence, we finally meet the real people that Langham based his characters on when they come to his home for his birthday. Rather than the angry and unhappy Claude and Sonia and the passive Woodford we’re used to, their inspirations are warm and supportive and loving and kind. Langham himself is full of good cheer. He’s still witty and sharp, but it’s abundantly clear that he loves his family. He has next to no memory of the vindictive story he was crafting the night before.

This difference between night and day makes Providence one of the best films about alcoholism I’ve seen. Anyone who has known an alcoholic is familiar with seeing them as two people – the one before they drink and the one after. Their frustrations and suspicions about other people, the hurtful things they say that they would otherwise suppress, are mistaken for “real” when they’re drunk. When sober, they can be loving and kind and conveniently forgetful. One of the visual jokes in Providence is that everyone always seems to have a glass of white wine on hand. But it also shows how much Gielgud’s character thinks about drinking. It’s a constant preoccupation. The final line of the movie comes after his family has left and Langham is alone. “I think there’s time for just one more,” he says, pouring himself a glass of wine. It’s optimistic, in that he still has some time left even though he is dying. But it’s also an alcoholic’s motto: there’s always time for one more.

Providence can be found online at http://rarefilmm.com/2017/12/providence-1977/