It all begins at the Universal Theatre, probably a reference to the Universal Pictures logo seen seconds before. Inside a projection booth, Shemp Howard, a familiar face seen here between his stints as one of the Three Stooges, is loading a film. We see the movie playing as he watches from the booth. It’s a standard musical with glamorous chorus girls descending a large staircase. But unexpectedly, the stairs go flat, turning into a ramp the ladies slide down. They fall not just off the set but all the way down to Hell where they are tormented by male demons in bathing suits and cheap-looking hoods with horns. A catchy theme song promises “Hellzapoppin’…anything can happen and it probably will.” In this Inferno, people are packed inside cans and ladies are roasted on spits. A taxicab arrives and dispenses its passengers: farm animals and our guides, Ole Olsen and Chic Johnson, Virgils in zoot suits.

The cab driver (who’s a dwarf of course) presents them with an outlandish bill, so they literally blow up his cab — it explodes when they breathe on it. Olsen addresses the viewer: “Pardon me just a moment, folks,” then begins talking to the projectionist showing the movie, who is currently preoccupied with hitting on a zaftig usher. Irritated, he asks “What’s the matter with you guys? Don’t you know you can’t talk to me and the audience?” Olsen and Johnson respond with some self-satisfied giggling. We then see the film run in reverse until the moment of the taxi’s explosion is replaced by its driver turning in a jockey, who flies off his horse. Olsen narrates the jockey’s flight as if it were a horse race. Moments later, they meet the director of the movie we’re watching, who argues that movies need more of a story…

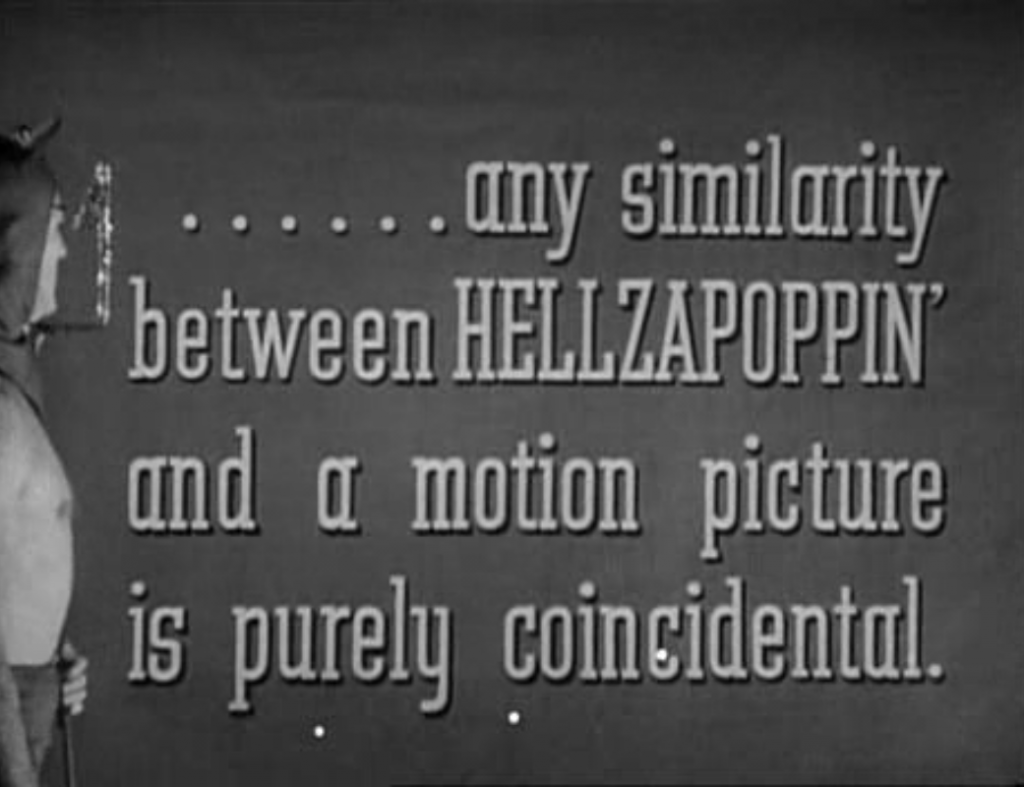

And that’s just the first six minutes or so of Hellzapoppin’ the film adaptation of Olsen and Johnson’s revue that ran on Broadway for 1404 performances, a record at the time. In its continual trampling of the fourth wall and jokes based on characters at the mercy of the medium in which they exist, it’s somewhere between Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr., in which a film projectionist falls asleep and enters a movie, and Duck Amuck, Chuck Jones’ inspired cartoon where Daffy Duck is tormented by a godlike creator who keeps arbitrarily changing his reality.

It’s unfortunate that the director’s argument in favor of a story wins out. Soon we’re in a daft but all-too-recognizable musical about “putting on a show” that’s complete with a love triangle, phony royalty, snooty rich people, complications, and misunderstandings. Luckily this is all seasoned with Olsen and Johnson’s meta gags. At one point, a confrontation in the projection booth knocks the movie’s framing out of sync, leaving Johnson trapped above the frame line at the top of the screen while Olsen, at the bottom, tries to save him. When the projectionist chooses the wrong reel, Olsen and Johnson are trapped in a Western, bystanders in a cowboys-and-Indians fight. The requisite dreary love song is undercut by messages superimposed onscreen imploring audience member “Stinky Miller” to go home. Eventually, the lovers interrupt their song to ask Stinky to leave. We see a little boy in silhouette walk across the screen before they resume singing.

Apparently, the stage version was even wilder. It’s a shame that they didn’t try to create a feature length absurdist musical, eschewing story and characters in favor of self-conscious and silly experiments in form. These things can work in a live show, but I’m curious how long an audience will tolerate such playing around without a larger narrative in film. There’s a reason why cartoons and experimental movies are generally shorts.

One can’t say Hellzapoppin’ mixes different kinds of gags because that would imply a blending. The jokes are cacophonous — they clash — and depend on an audience’s knowledge of how movies are made and contemporary Hollywood stories. This sense of playing with form and trusting the audience is savvy enough to get it can be found in Citizen Kane, also released in 1941. In My Lunches With Orson, Welles refers to Citizen Kane as a comedy. “Not a fall-in-the-aisles laughing comedy, but because the tragic trappings are parodied.” Even though it came out just three months after Kane, Hellzapoppin’ contains a joke about Welles’ film, an impressive turnaround time. Walking past a child’s sled with “Rosebud” painted on it, Johnson comments “Huh, I thought they burned that thing.”

Hellzapoppin’ is rarely screened on television, and rights issues have kept it from being released on home video in the US, though there’s a good copy currently on YouTube. Even if you don’t watch the entire film, the justly lauded Lindy Dance sequence is one of the best dance scenes ever filmed — it starts at 48:00. A group of servants, movers, cooks and maids, all African American, take a few minutes’ respite while getting the house ready for the Big Show that evening. What starts as an impromptu jazz session soon explodes into a frenetic dance. The moves are pushed to the point that the dancers are literally throwing each other, then catching their partners without missing a beat. They’re so fast that it feels like the film is speeding up, but this is the one time Hellzapoppin’ doesn’t rely on cinematic tricks. The scene is captured in long shot and long takes to better appreciate the incredible athleticism on display. Many of the other numbers in Hellzapoppin’ exist on the “Dated ↔ Corny” continuum, but this sequence, segregated from the rest of the movie just as its performers were from the other characters, still feels fresh today.