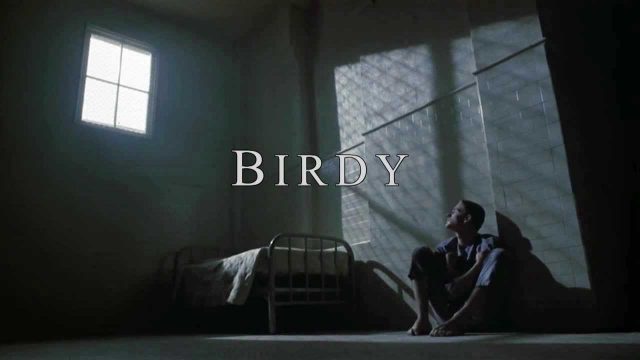

Like the William Wharton novel it’s based on, Alan Parker’s film Birdy is concerned with pairs, dualism. Two friends grow up, go to war, come back damaged. Nicolas Cage’s Al, his face wrapped in bandages, visits his best friend Birdy, played by Matthew Modine, at an army hospital. Birdy is physically unhurt but catatonic. Befitting the ornithological obsession that gave him his nickname, he spends all day crouched like a bird in his cell while Al tells him stories about their friendship, desperately looking for some sign of recognition. Al the wrestling champ defines himself physically, whereas Birdy is all spirit: he yearns to fly. Past and present, war and peace, the inner world and the outer, entrapment in a cage and freedom with nowhere to go.

Thankfully the movie doesn’t play as schematically as that description makes it sound. The focus is mainly on Al’s heartfelt but bumbling monologues, which frame flashbacks to their youth. Wharton’s novel emphasizes this duality more. Its chapters alternate between Al and Birdy’s points of view. The heart of the novel concerns Birdy’s dissociative disorder, in which he has a sequence of dreams wherein he thinks he is one of the pet birds inside his homemade aviary. This identification becomes so strong he eventually “fathers” chicks and sees his human self as a boy outside the cage watching himself and the other birds. This section takes up almost a fourth of the book but is largely jettisoned by the movie apart from some voiceovers by Modine.

Considering its themes of madness and war, Parker’s film is fairly restrained; surprising given that it was his first film after Pink Floyd: The Wall, which often seems like an attempt to outdo the excesses of Ken Russell. Both Birdy and The Wall feature shellshocked protagonists and the lingering effects of a war after the fighting is over. They’re PTSD movies. In the book, it’s World War II that damages Birdy and Al, but scriptwriters Sandy Kroopf and Jack Behr changed it to the Vietnam War because it was closer to their experience. Updating the story might have added a more contemporary relevance, but the movie doesn’t really have anything to say about Vietnam. It’s just a war, which contradicts the idea driving almost every other movie about Vietnam, that it was a war unlike any other.

One of the most admirable things about Birdy is how quiet and subdued it is. It could easily have slipped into sentimentality, preciousness, or overwrought messaging. This restraint is noticeable in how it approaches nostalgia, symbolism, and homoeroticism. The affection for the past isn’t overdone or cloying; it’s kept to a few needle drops of Richie Valens’ “La Bamba.” There’s some clunky symbolism (such as the shot of Modine lying on the floor in a crucifixion pose or the way the rooms separated by chain link fences are shot to resemble cages) but it’s not as bad as it could have been. Any film about the bond between men lends itself to a homoerotic reading. Early in the movie, Al answers the insinuating question about their friendship, “How close?” with “We weren’t queer for each other, if that’s what you mean.” But a conversation in one of the flashbacks reveals that Birdy not only doesn’t desire women’s bodies, he doesn’t even understand them. This leads to one of the movie’s funniest yet saddest moments: his befuddled reaction when his prom date removes her top, offering herself as a reward for his decency.

Most discussion about Birdy usually focuses on one element rather than the movie in toto. It has one of Nicolas Cage’s best performances before his acting devolved into either pleading hangdog pathos or manic scenery-chews. Cage has great chemistry with Modine, who conveys Birdy’s dreamy side without seeming like a wimp or insufferable “holy man.” (Modine originally auditioned for the part of Al.) He plays him similar to the boyish, slightly off, brainy characters he would play in Full Metal Jacket and Married to the Mob. It’s a shame he and Cage haven’t made any other movies together.

For some, the movie is best remembered as the first film to feature a score by Peter Gabriel. Unlike the original score he created five years later for Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, this one reuses some music from Gabriel’s third and fourth solo albums. He joined the project after Parker showed him a rough cut of the film, though it’s surprising how closely the songs from his third album fit the themes that were expressed more fully in the novel. “Not One of Us” is about xenophobia but speaks to how Birdy doesn’t fit in either the avian world of his dreams or the human world of his reality. The final section of the song provides the driving rhythm for a scene in which one of his favorite birds escapes and flies along the neighborhood streets, free for the first time. The instrumental from “Family Snapshot,” about an unhappy boy and his fantasies, provides a poignant melody when Birdy first “meets” his beloved canary Perta at the home of another bird fancier. Gabriel also uses the polyrhythmic, African-inspired tracks from Security, his fourth album. They’re completely anachronistic to this story, but it works. Better yet, watching Birdy thirty-five years after it was released, the music never feels dated. It’s certainly of its time, but this mix of eras, a contemporary 1980s soundtrack illustrating a story that takes place in the 1960s, prevents it from being tied to only one period of time.

One final note: One of the things people remember best about the film is the ending, which I won’t discuss for fear of spoiling it or worse yet, building it up so high that it inevitably disappoints. Suffice to say, it ends on a joke, a humorous grace note that makes you hope for the best while still accepting the pain that came before. “What?”