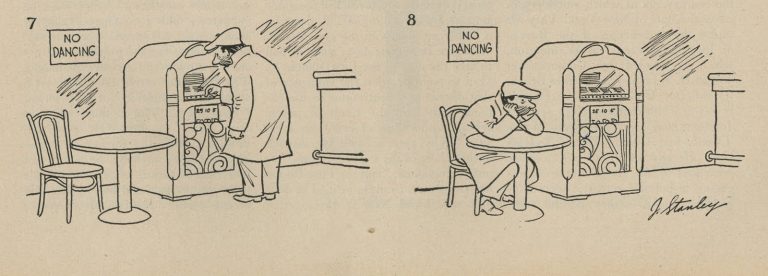

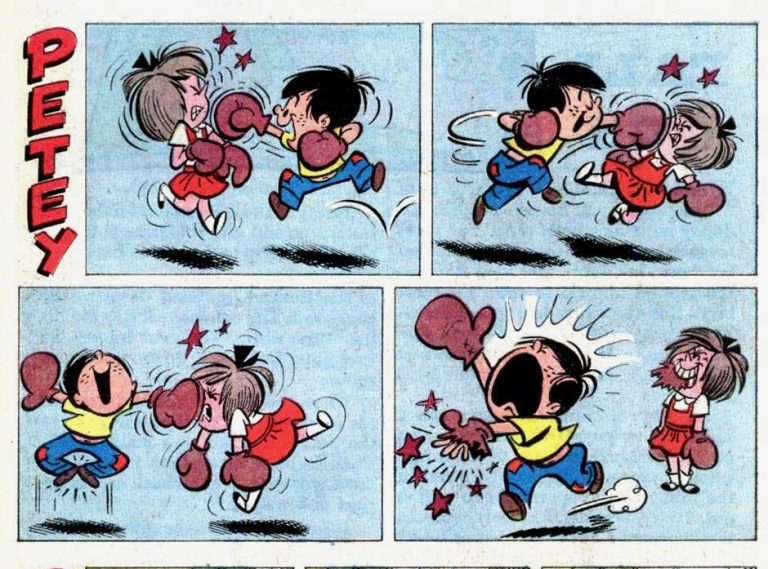

If John Stanley’s an unsung genius, his collaborator Bill Williams might be even more so. At least Stanley’s carved out a cult following among the little world of funnybook fans — Williams never even did that much. And that’s a shame — Williams’ elegant linework on Kookie and Around the Block with Dunc and Loo perfectly splits the difference we talked about yesterday between Tony Tallarico’s finished artwork for Thirteen Going on Eighteen and Stanley’s own: as clean and polished as the one without sacrificing any of the rough, sketchy energy of the other. Let’s go further — if other artists deadened the energy of Stanley’s layouts, Williams’ only enhanced them, his sweeping brushstrokes making the characters seem to move like living beings.

Williams had actually come up with the characters independently of Stanley: he created Dunc and Loo for a newspaper comic strip, and Petey, as “Pepe,” would have been the star of another one. Dunc and Loo are two teenagers living in the Airy Arms Apartments, who spend most of their time hanging around Sid’s corner store. Loo (and his children’s children) have been barred for life, which doesn’t seem to stop him. As the series goes on though, the “Dunc and Loo” part of the title becomes less important than the “Around the Block,” as Stanley introduces more offbeat characters like Strongboy Stoop and the Klobble and Klinka families, who get progressively more screentime and eventually become the stars of their own stories. Even Petey, added to the book as part of some arcane Postal Service rule requiring comics to feature an unrelated backup story, eventually was absorbed into the main cast. Some issues anticipate Jack Kirby’s ambitious “Fourth World” project a decade later or the modern-day “event crossover,” playing out one plot across multiple smaller stories about different characters.

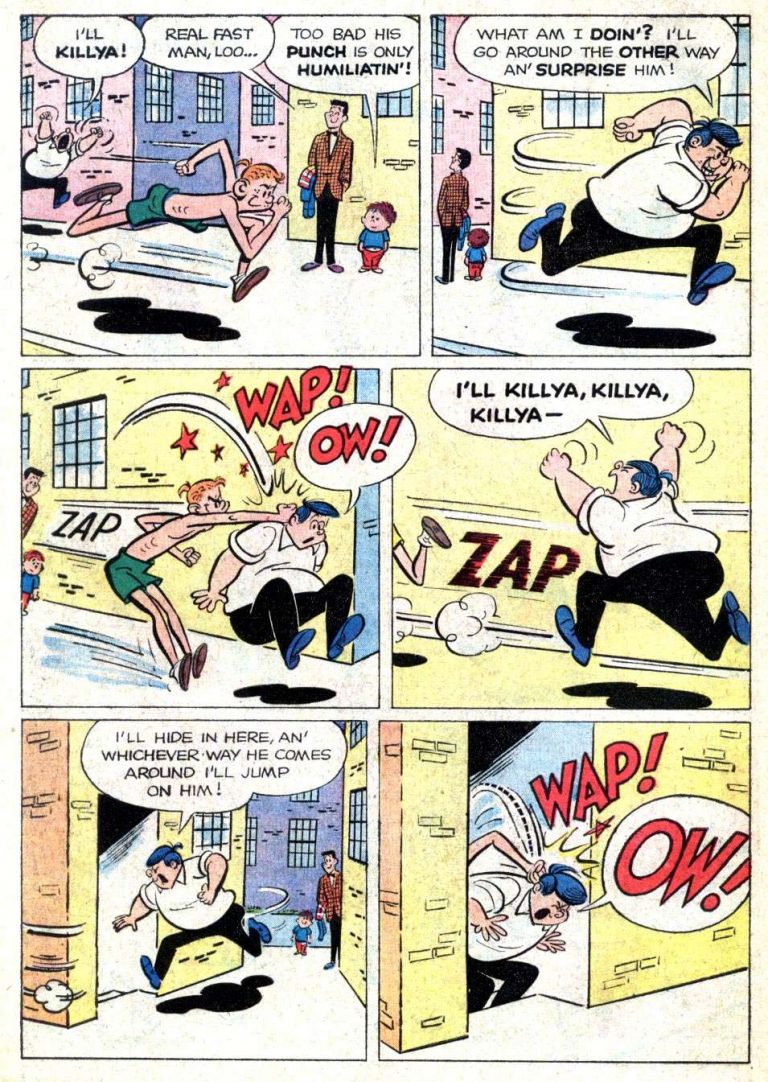

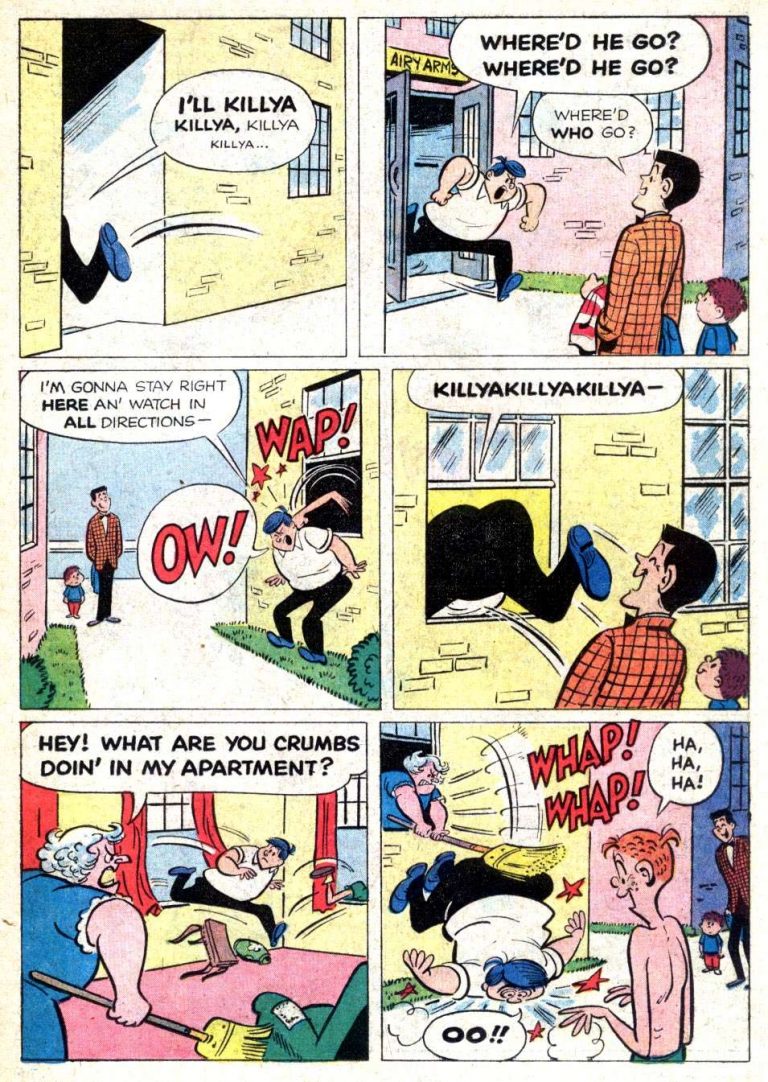

If the heightened emotions of Thirteen are all too real, Dunc and Loo goes further than anything else this year into cartoon exaggeration, with hilarious results. There’s always the threat of violence from Buddy O’Bunnion (brother to Beth, the object of Dunc and Loo’s affections), punctuated at just the right intervals with threats to “roon ya!” or “killya, killya!”

And then there’s the spectacular setpiece of Mister O’Bunnion, his foot smashed by Dunc’s little brother Joey, being dragged across the building frozen in a silent scream.

This was easily my favorite of Stanley’s ‘62 comics (I went ahead and kept reading it after I finished all the relevant issues), but it’s surprisingly hard to analyze. Maybe, if Mark Twain (or whoever keeps getting quoted as Mark Twain) was right that dissecting comedy kills it as surely as dissecting a frog, we should let the series speak for itself with some of Stanley’s finest deadpan, slapstick, and deadpan slapstick (but not, far as I can tell, any tragical-comical-historical-pastoral.)

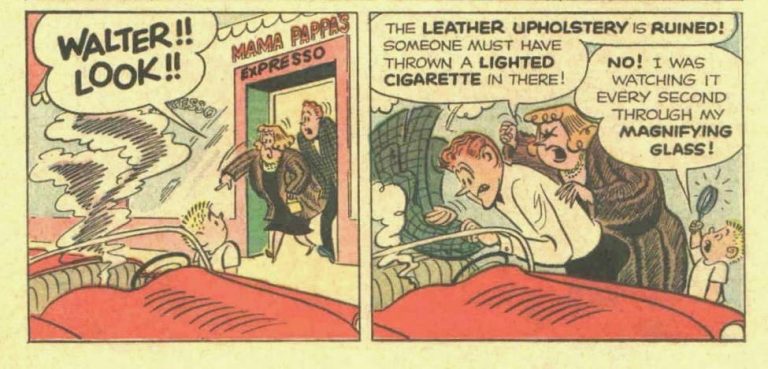

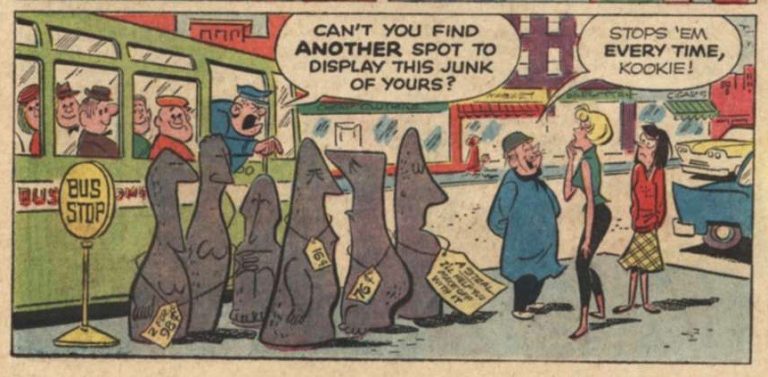

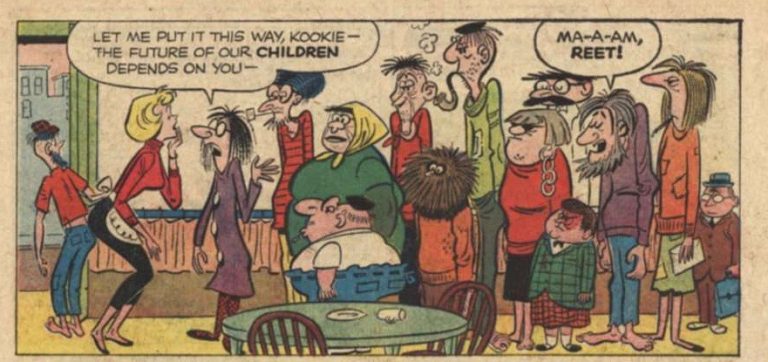

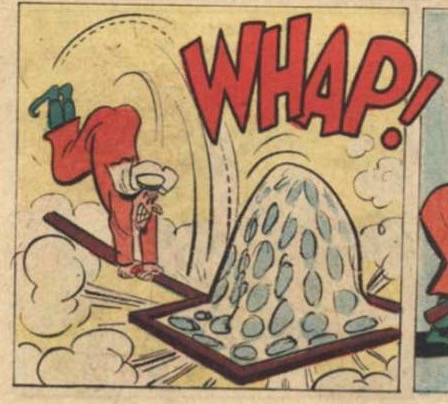

While all this was going on, Stanley and Williams were also collaborating on the beatnik series Kookie. It would only last two issues, and there’s plenty of likely culprits — it cost more than the average comic, it was aimed at an older demographic, and the beatniks were just then on their way out to make way for the hippies. Still, as a Greenwich Village native, Stanley was able to bring some authenticity to the concept. He also brought a new style of storytelling to the first issue — instead of a few quickies divided by title cards, the story just keeps moving from one loosely connected incident to another, beginning when Kookie’s roommate gets woken up by bongos early in the morning and ending when Kookie gets back from work in the evening. Along the way, Stanley sometimes loses track of her entirely, roving around among the patrons of her workplace, Mama Pappa’s Expresso. Purposely or not, it’s the perfect way to reflect a subculture obsessed with free verse and freeform jazz. Maybe Kookie was too good to last, or maybe it wasn’t — by the next issue Stanley’s already resorting to ethnic stereotypes and dropped the freewheeling structure of that first adventure for the standard format of quick, unrelated stories narrowly focused on his hero. But Williams still has plenty of fun, getting to design modern art parodies for a sidewalk art show and a whole gallery of bizarre Mamma Papa’s regulars, and even the stereotypical sheik provides fodder for some memorable slapstick with a running gag about his enormous flyswatter.

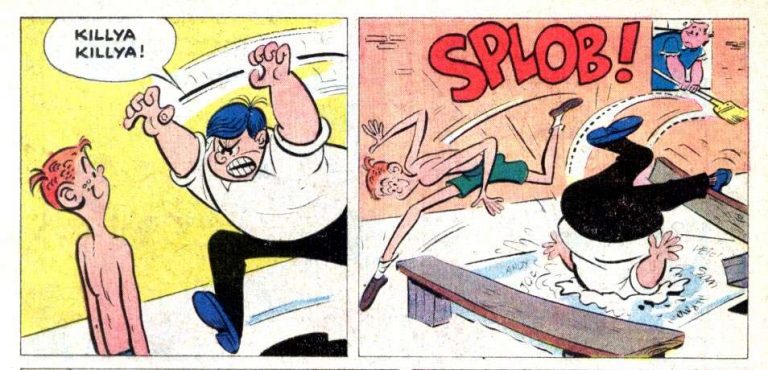

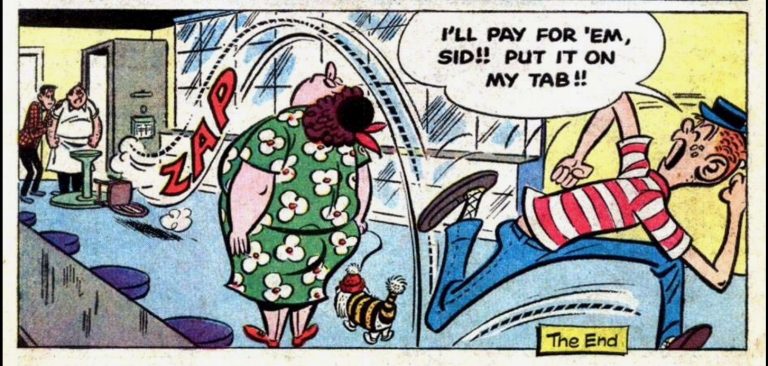

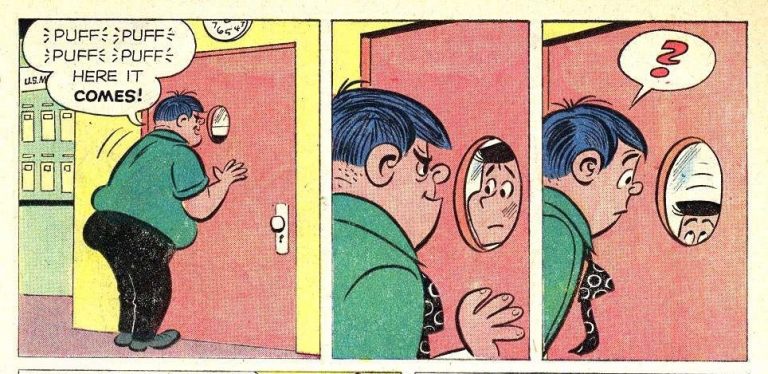

There’s also this scene, which I don’t have anything to say about, but it made me laugh, so here it is anyway.

There’s also this scene, which I don’t have anything to say about, but it made me laugh, so here it is anyway.

Thirteen and Dunc and Loo stand out as the best, most consistently funny and expertly crafted of Stanley’s ‘62 work. But the most fascinating stories sent him much further afield. The year marked his one attempt to write horror with Tales from the Tomb and Ghost Stories. They’re not as expertly crafted and certainly less funny, but these stories are kind of the opposite of Dunc and Loo. Where one was so perfect it doesn’t give me much to write about, these rougher attempts are ripe for analysis.

This might seem like a departure for him, but you don’t have to look too hard to find the resonances with his humor work. Little Lulu and her friend Tubby frequently met up with ghosts and goblins, most memorably in the genuinely frightening “Guest in the Ghost Hotel.” But the seeds of these stories are most present in the improvisational child logic of the fairy tales Lulu would invent to distract her destructive little neighbor Alvin and the dream logic of his take on Raggedy Ann. Even though the series would continue without him, Ghost Stories is the perfect title for his version of horror, less connected to the world of written fear fiction than the kind of stories kids would make up to scare each other around the campfire. Stanley’s expertise in child psychology makes these stories stand out — even Tales from the Crypt, whose narrator would always address the audience as “kiddies,” mostly focused on adult victims, but Stanley isn’t shy about putting kids in harm’s way. This makes the stories, even the ones featuring adults, part of a much older tradition – more Grimm than grim.

Like Linda Lark, Stanley’s horror stories sometimes suffered from more blandly realistic artwork that deadened his cartoon compositions. Sometimes Stanley and his collaborators seemed not to be communicating: Ghost Stories’ “The Black Stallion,” for instance, features a character named Pudge (any relation to Tubby?) who looks weirdly svelte under Gerald McCann’s pen.

And then there’s “Crazy Quilt” in Tales from the Tomb. The entire story is told mostly in increasingly frenzied close-ups as a woman tells of her horrible encounter with a man with a quilt sewed onto his skin. It’s a surreal, frightening image: Frank M. Young describes it as “sheer nightmare lunacy. It is a perfect sort of childish bad dream. Being quilted, in the cold light of day, may not strike a mature adult as terrifying. It might actually be a virtue in colder climates. But from the viewpoint of a child, to whom the world is a sweltering mass of unknown and untested things, this concept is most potent. The idea that a comforting, warming object like a quilt could become something frightening and dangerous is appropriate for a child’s imagination.” But then, after sitting with this horrible image for four pages, we turn the page and see…this.

It’s true that the task of visualizing this character without losing the horrible terror of the concept is a challenge, but this cuddly, chunky thing on the page proves Tony Tallarico wasn’t up to it.

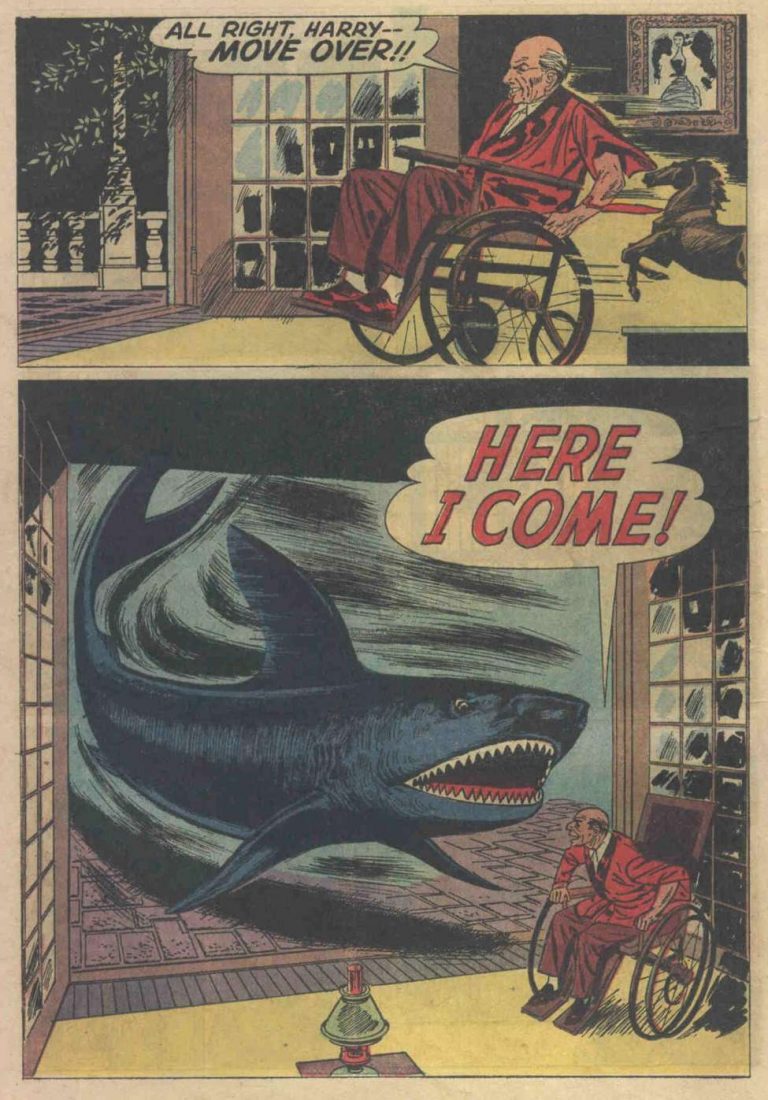

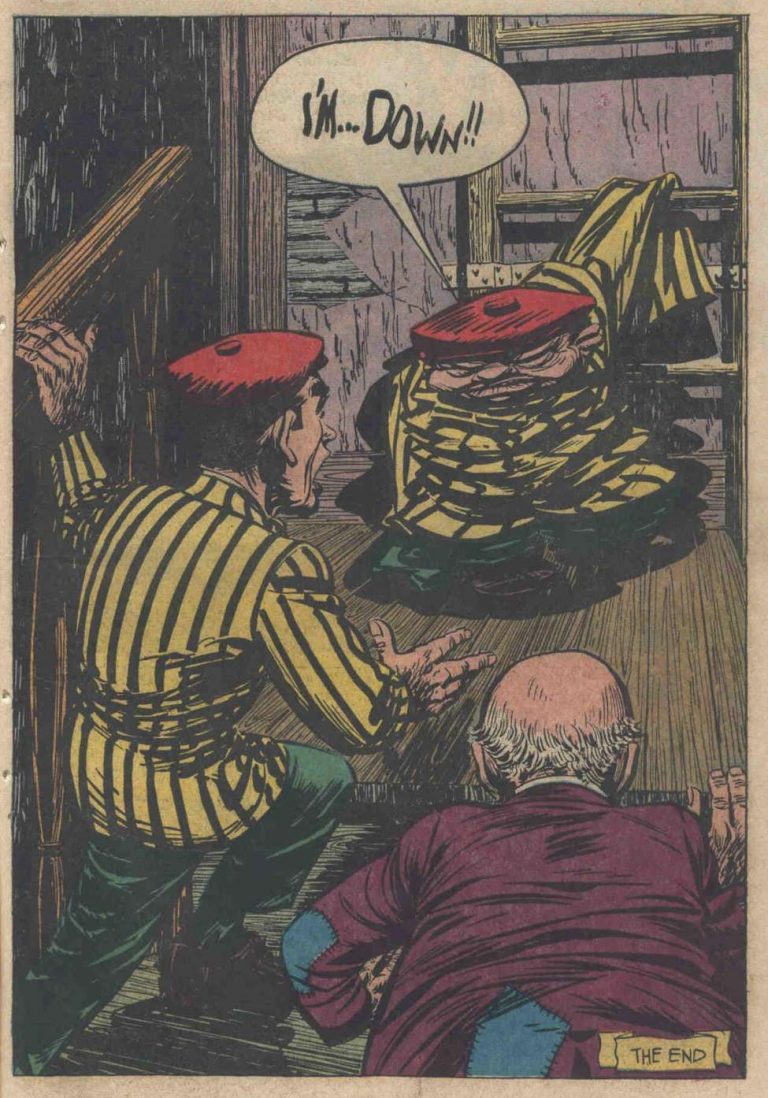

Fortunately, Stanley’s horror is full of strange and haunting images that even the worst artist couldn’t ruin: enormous, levitating ghost sharks, a striped rug as the portal to a monster’s lair, the results of smashing a voodoo doll. How could they? This is the kind of horror that lives and breathes in a child’s crayon scribbles.

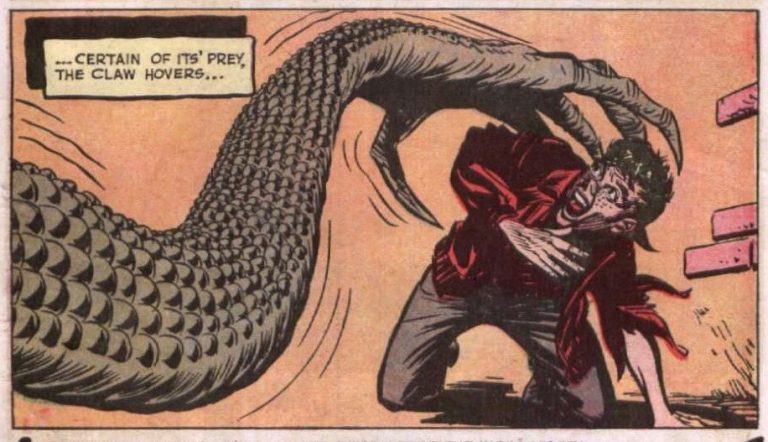

And Stanley’s collaborators can come through with moments of surprising artistry, like Ed Robbin’s almost tangible texturing on the scales of the Monster of Dread End’s snakelike arm.

Even when these stories are bad, they’re good. The half-baked deus ex machina ending of “Dread End” (where an entire regiment of cops appear out of nowhere to shoot the monster to ribbons) is terrible waking logic, but it’s excellent dream logic. And its nonsensicality warps into something weird and haunting: how could they let our child hero be tormented so long? How long had they been crouching in the shadows of the abandoned neighborhood? “The Werewolf Wasp” has a similar strangeness, as, instead of discovering the secret of the title creature, the hero finds the kindly entomologist is a horrible monster just as the wasp inexplicably grows enormous and saves his life. The ending, like Bender’s cigar on Futurama just raises further questions.

You might think it’d be hard to apply the techniques of humor to horror, but Stanley’s deadpan absurdity carries over effortlessly to the foreign genre. His characters frequently describe ridiculous events, turning over-the-top visual jokes into subtler verbal ones, letting the reader’s imagination make them even funnier than he could ever draw them.

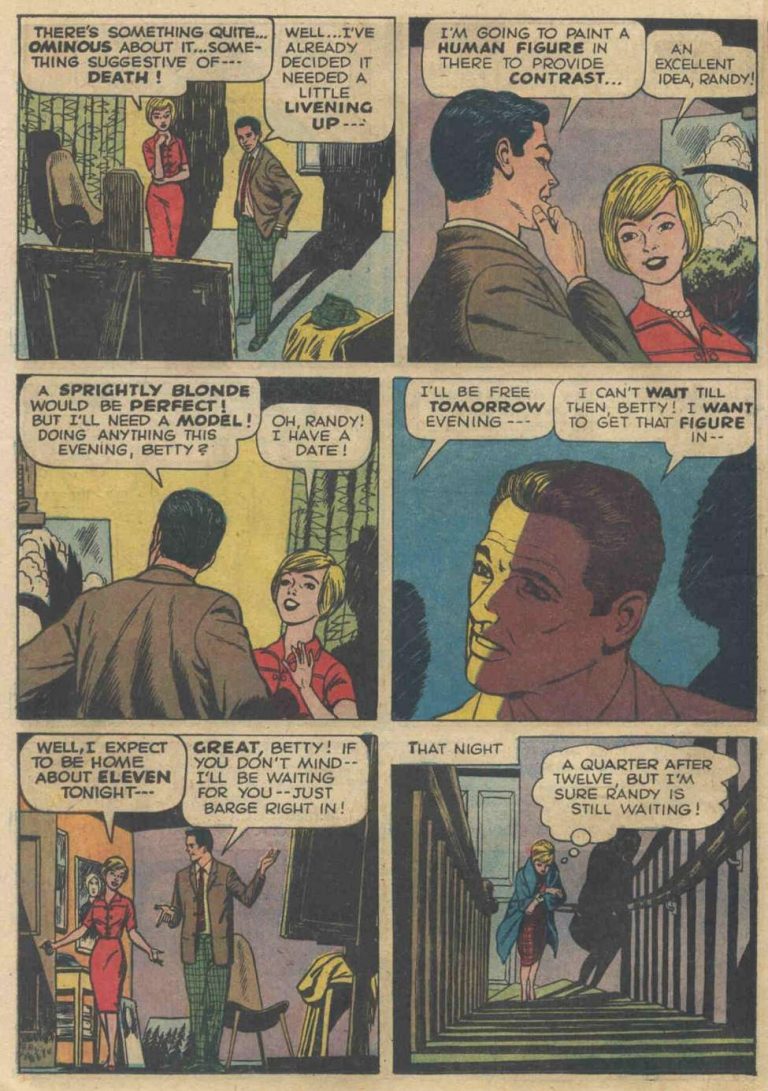

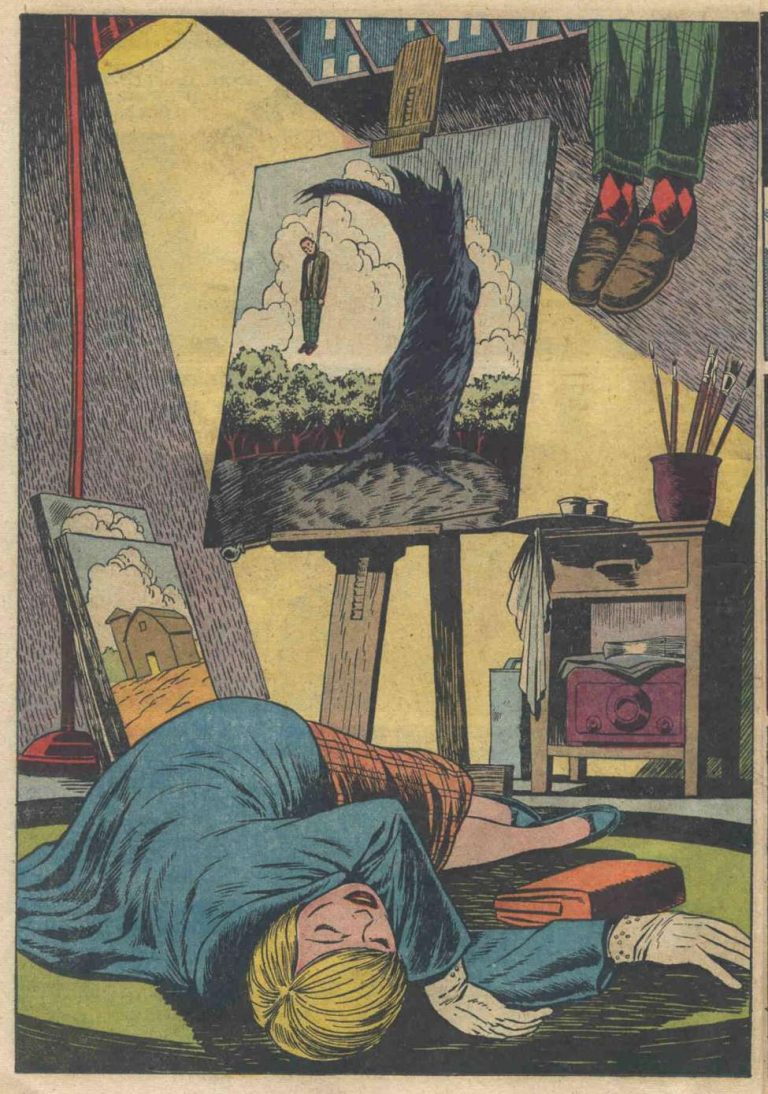

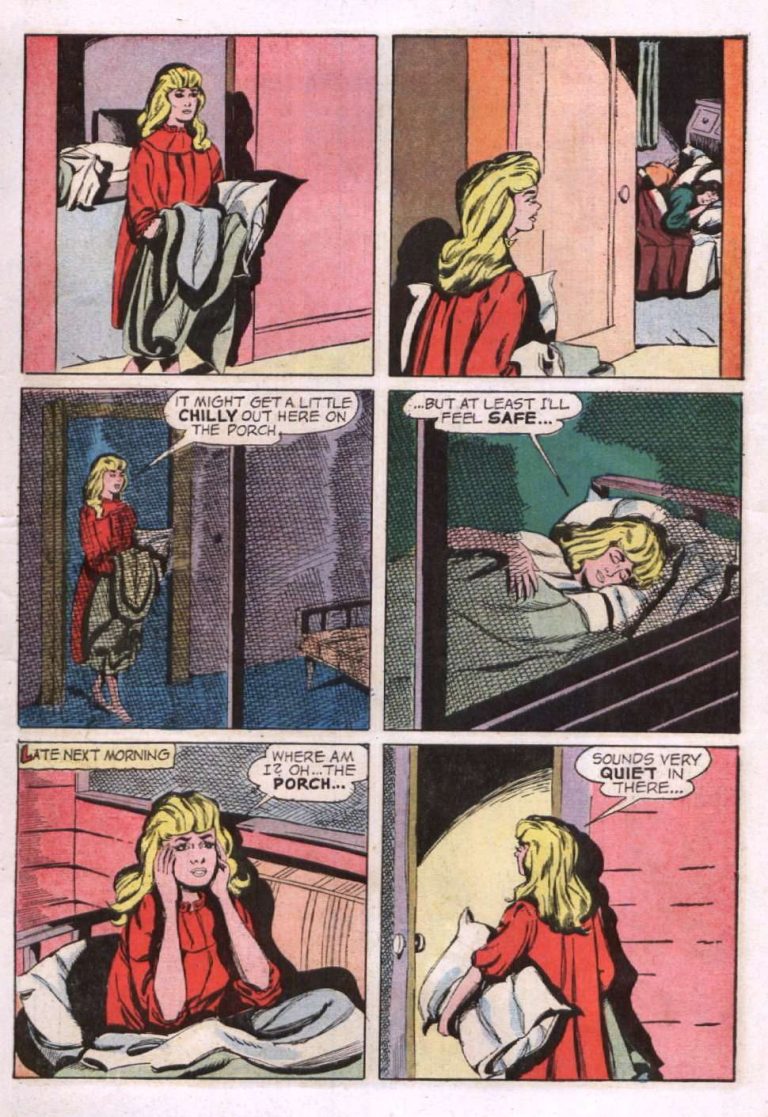

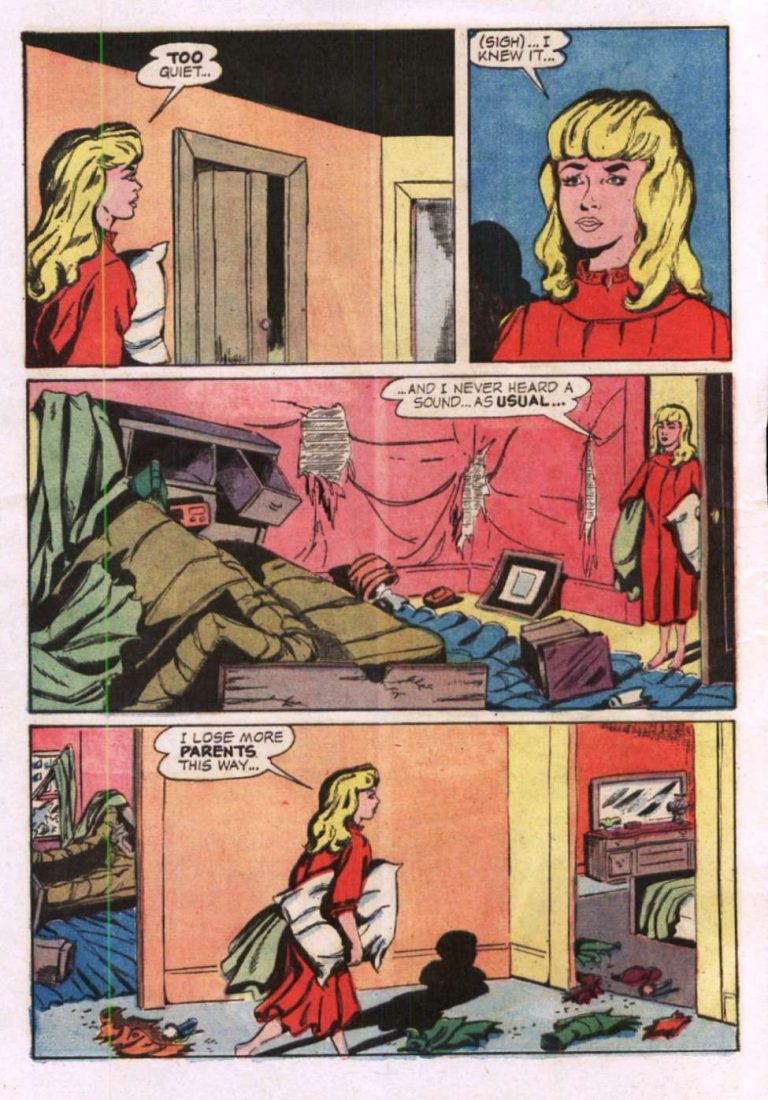

It’s one of the founding rules of horror that what we don’t see is scarier than what we do could ever hope to be, so Stanley’s style makes the leap beautifully – not to mention being a good way to keep these gory stories kid-friendly. For instance, there’s “Still Life,” which shows the aftermath of a gruesome murder for a reveal far more disturbing than the act itself could ever be.

Stanley creates many of his monsters by shadowy suggestion: we only see the Monster of Dread End’s disembodied arm, and Mr. Green appears as a slouching, formless figure, only glimpsed from the back.

“The Door…” is an even more perfect showcase for Stanley’s decompressed style and dry wit than his humor books, as the mysterious child slowly surveys the aftermath of her foster parents’ death at the hands of an unseen bogeyman and casually remarks, “I lose more parents that way…”

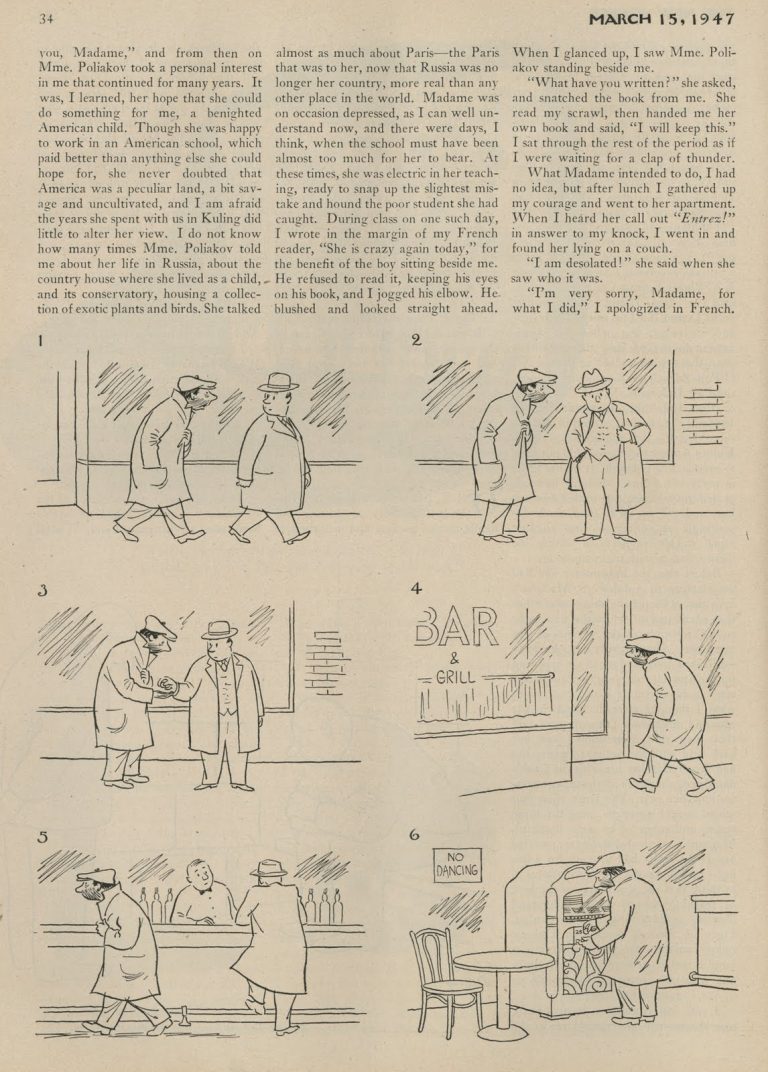

So here we have an unseen genius, toiling in a disreputable genre of a disreputable medium. But it didn’t have to be that way. Fifteen years earlier, he achieved every cartoonist’s dream: he was published in The New Yorker. He turned down a contract because he didn’t want to be tied down — a sad irony knowing he’d spend the next twenty years working for one side or another of the Dell/Western split. It’s a beautifully bittersweet piece — not just for its content, but for the glimpse of the fame and success he always deserved but never achieved.