“Seymour Moskowitz is the new symbol of hope in America”

Leave it to John Cassavetes to put it so boldly. His take on the “youth-market” picture (The Graduate, Easy Rider, Five Easy Pieces) places the free-spirited, older hippie Seymour in a screwball comedy that is more serious and complex than what the suits at Universal were expecting.

Cassavetes called the suits’ bluff. While he uncharacteristically brought the film in on time and on budget, Seymour was played, not by a star, such as Jack Nicholson (whom the studio suggested) but by Seymour Cassell, whose high-wire performance in Faces inspired Cassavetes to write a film around him. Cassavetes told Cassell to grow his hair long for the part; he would be acting alongside Cassavetes’s wife, Gena Rowlands, also a standout performer in Faces.

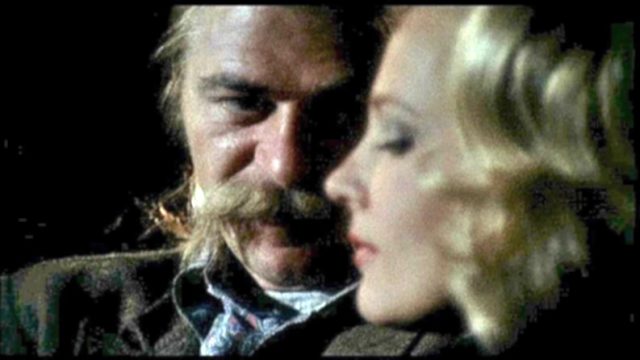

In Minnie and Moskowitz, Rowlands plays Minnie Moore, a buttoned-up LA museum worker, whose romantic expectations are tempered only by her concerns about getting older. Seymour, a ponytailed and walrus mustache-ed car parker newly arrived from NYC, falls madly in love with her. It’s a gender-switch on the mismatched lovers in screwball comedy. As Marshall Fine explains, the generic convention is that a reckless woman pursues a reluctant man (Bringing Up Baby, The Lady Eve): the reversal transforms the “unthreatening [and pleasurable male] fantasy” into a more troubling, and what comes across now as stalkerish, scenario.

No matter how it’s contextualized, the narrative plumbs the mysteries of love, writ large; Cassavetes openly wondered why people would even want to get married in the early 70s. He draws, as is his tendency, on autobiographical elements. The scenes in the film uncannily resemble his courtship of Rowlands. Reportedly, upon first seeing her, he made up his mind that he would marry her—and Rowlands acted reserved and distant (for example, wearing sunglasses even at night, like Minnie does). And Cassavetes and Cassell were close friends, sharing a wild streak.

Cassavetes wanted the “hopeful” undertone of screwball comedy, but without the cuteness. Therefore he went behind the backs of the actors to push them into more raw performances. Granted, Cassavetes knew that Rowlands had acting chops to burn. But he also knew that Rowlands would play it by the book, finding a way to signal to the audience that Minnie would be, in the wake of two disastrous romantic encounters, readily open to Seymour’s advances.

To begin, Cassavetes makes Minnie completely disillusioned with love. In the opening sequence, Minnie, after sharing her frustrations with a gal pal, arrives home late at night to find her lover, Jim, waiting. The twist is that Jim is played by Cassavetes. Rowlands kept asking who would be playing the role; Cassavetes made sure that Rowlands wouldn’t know (thus keeping her off balance) until the scene was shot. Jim’s idea of foreplay is to slap Minnie down in a fit of jealous rage. Although he’s a horrible person, Jim is played by Cassavetes as a charming bad boy, and Minnie/Rowlands can’t resist him.

The next morning Minnie arrives at the museum and meets Zelmo Swift, with whom she’s been set up on a blind date. They go to lunch, and what ensues was carefully orchestrated by Cassavetes. Playing Zelmo, Val Avery wanted to turn his character into a touching portrait of an older, lonely man. That’s not what Cassavetes had in mind, and proceeded to wind him up until he looked sweaty and desperate. The result is one of the cringiest first dates that you’ll ever see on film. As Zelmo’s self-composure disintegrates right in front of her (and our) very eyes, Minnie’s repeated attempts to make a dignified exit bring out, in full force, his bullying act: “What is it with you blondes? You all have some Swedish suicide impulse?”

Parking cars at the restaurant, Seymour watches Minnie run outside, while Zelmo angrily chases after her. He intervenes, and the two men throw punches at each other. Seymour strikes a decisive blow, and Zelmo drives away, leaving Minnie stranded.

Seymour gets in his truck and yells at Minnie to come with him. He thinks he’s rescuing a damsel in distress, but she has other ideas, and has him drop her off at the museum. Jim is already there and breaks up with her on the spot, in front of his son, telling her that his wife tried to commit suicide.

The stage is set for the romance between Minnie and Seymour. They argue, as mismatched lovers in screwball comedies will, and go on a romantic adventure that is as wild as any trip through outer space. Cassavetes accentuates their driving around LA with “The Blue Danube Waltz,” heard in 2001: A Space Odyssey, to make this idea even more striking.

Cassavetes, however, contrived to get Rowlands to find the very idea of acting out a romance with Cassell practically unthinkable. Cassell, having a real-life crush on his best friend’s glamorous wife, was goaded by Cassavetes into interrupting Rowlands’s afternoon beauty nap before a crucial scene that was to be shot that night. As if Rowlands wasn’t pissed off enough, Cassavetes then accused her of holding back when she was acting with Cassell.

In this scene, which takes place in the parking lot of a downscale, but hip, country and western venue, Rowlands has a ferocious energy, even as Cassell is trying to sweeten his approach. When she encounters at the entrance some well-heeled friends slumming it, she blows him off. In retaliation, Seymour drives away and strands her (just like Zelmo did).

Well, there has to be a reconciliation, and Seymour, after coming to his—relative—senses, returns and acts out his love for Minnie in her bathroom in a way that borders on the unimaginable. It now becomes Minnie’s chance to go for broke, and she kisses him.

As Fine puts it, Cassavetes “shows all the reasons they are wrong for each other, then decides that the heart can trump the brain.” They invite their mothers to a restaurant in an impromptu wedding rehearsal dinner that goes off the rails when Seymour’s mother (played by Cassavetes’s own mother) nearly sabotages the whole deal. Minnie’s mother (played by Rowlands’s own mother) is stunned.

Needless to say, Cassavetes plays with our own expectations about love—with Minnie and Seymour as our surrogates—further disorienting us by the compression of time through New Wave-like editing. Even the wedding appears surreal, the priest forgetting his lines (which actually happened during Cassavetes and Rowlands’s wedding). The closing backyard family scene, shot in hazy sunshine, feels like an out-of-time moment. A fairy tale ending? The future? Could it be both?

Sources:

Marshall Fine, Accidental Genius: How John Cassavetes Invented the American Independent Film (New York: Hyperion, 2005)

Ray Carney, American Dreaming: The Films of John Cassavetes and the American Experience (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: U. of California P., 1985)

Ray Carney, Cassavetes on Cassavetes (New York: Faber and Faber, 2001)

Ray Carney, The Films of John Cassavetes: Pragmatism, Modernism, and the Movies (Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge UP, 1994)