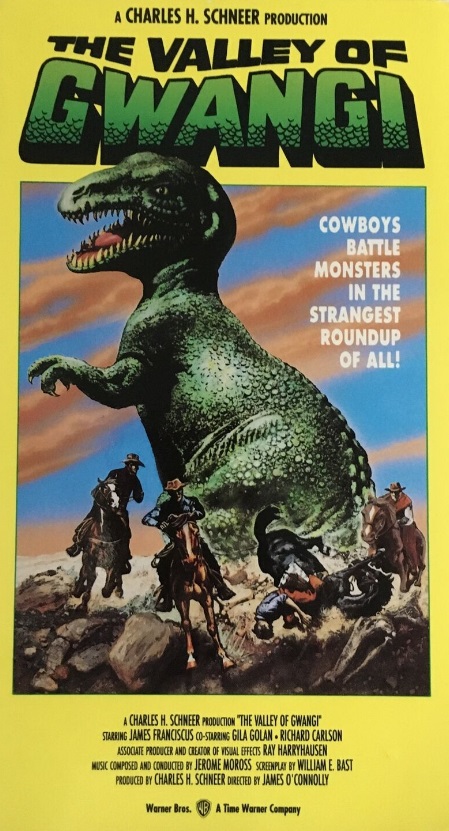

In 1968, 2001: A Space Odyssey rewired what audiences could expect from special effects. A year later, The Wild Bunch revolutionized depictions of action and violence in the Western. As Bob Dylan said about changing times, “why wait any longer for the world to begin?” But the old world was not yet done. Mad robots and vicious outlaws may have been the future, but in 1969, the techniques of the past could still let COWBOYS BATTLE MONSTERS IN THE STRANGEST ROUNDUP OF ALL!

The Valley Of Gwangi’s story of terrible lizards vs. incompetent trailhands came from Willis O’Brien, the maestro behind the effects in King Kong, The Mighty Joe Young, and ape-free silent classic The Lost World. O’Brien wrote the story in the 1940s, and it was later reworked into the 1956 film The Beast Of Hollow Mountain. The rejuvenated Mystery Science Theater 3000 crew took that one for a spin a few years back; I haven’t seen either the original or the Satellite of Love take, but I had plenty of riffs of my own while watching Gwangi’s humans, who take up a large amount of the early going. A tedious love triangle mixes with the economics of running a failing 1900s Wild West Show mixes with — worst of all — a plucky orphan boy; the acting is bluff and square-jawed and, in the case of Israeli actress Gila Golan, entirely dubbed. While the desert landscapes of Spain, subbing in for Mexico, are colorful and dry, the performances are pure cheese.

But the humans are not the point here. Ray Harryhausen is the point here. The stop-motion legend first shows his hand with the appearance of an actual tiny horse, none of your Lil’ Sebastian nonsense — this creature is the size of a housecat: an Eohippus, the actual mini-horse of the Eocene. The little guy scurries and cavorts across a dinner table and it’s charming as hell. Naturally, the carnies want to exploit this as a sideshow in a ridiculously stupid plan (this miraculous creature will be revealed riding another horse, truly devastating the yokel mind) but quickly come up with something less idiotic if also less safe — finding out where in the desert wastes Eohippus came from, and seeing if there is anything better to market.

Eohippus’ campus turns out to be a hidden valley that contains not subpar salad dressing but awesome prehistoric beasts. There is a pissy and threatening Styrachosaurus, the Triceratops on steroids; there is a heroic Pteranodon who flies off with the orphan before falling to the ground (damn dense orphan) where the ostensible human hero snaps its neck. There is briefly an Ornithomius, a human-sized lizard loping on two legs, but then there is Gwangi. An Allosaurus with an entirely earned attitude, he chomps down on the Ornithomimus (who has been so clearly set up as the low-level lackey the real bad guy will kill to show who’s boss, some things are eternal) and is more than happy to go after the humans before the presence of Styracosaurus convinces him to move along. But the humans aren’t ready to go. They see another opportunity here. It’s time to take Gwangi out of the valley.

A real fake thing is better than a fake real thing. Harryhausen’s creatures do not have the same texture or quite the same color scheme as the humans they menace. You can see, if you want to, how their fakery doesn’t fit. But why on earth would you want to? And just as importantly, why would you do the work of looking past Harryhausen’s work to do so? If the colors seem a bit off (Gwangi has an odd blueness) the creatures are still lit to blend in with the environments they’re not actually a part of. If they don’t have actual flesh, their “skin” and “musculature” and especially “teeth” are clearly tangible, undeniable things. And sor is their motion. The shot of the terrified tyke with the Pteranodon’s wings flapping and in all appearance lifting him off the ground, is marvelous, as is the extended sequence of the cowboys attempting to lasso Gwangi. Sometimes Harryhausen cuts to close-ups of the angry Allosaurus with ropes around his muzzle and no humans in sight, but he also has plenty of shots where the cowboys are throwing lariats on the dinosaur that is apparently in the frame with them despite not being there for “real.” It’s fantastic stuff, only topped by Gwangi finally getting a chance to eat a dude. Will the cinema ever improve on an image of a terrified man in the mouth of a T. Rex (or its non-union Jurassic equivalent)?

A fortuitous (for the humans) rockslide lays Gwangi low, enough for the remaining cowpokes to capture him and wheel the bound beast across the desert in a giant cart. It’s an oddly surreal image. And at this point in crafting the story, O’Brien understood that if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it — the greedy captors hold a giant exhibition of their furious prehistoric monster and in a shocking turn of events, the creature gets loose and starts fucking shit up. Gwangi is not King Kong, his size appears to top out at 20 feet tall; and midsize Spanish — I mean Mexican cities are not the Big Apple, but our hero still does some damage. And Gwangi is our hero, dammit. Like Kong, it’s his name on the poster! But more importantly he is boss as hell, he takes down a surprisingly hard-to-kill elephant before hitting the streets and stomping around, fully pissed at being out in this new world and eating quite a few people who have displeased him. Can any of us say we would do differently?

And while climbing anything, let alone a skyscraper, is out of the question for a large carnivorous theropod (those little arms!), Harryhausen comes up with a finale to rival Kong’s. The remaining cast finally finds verisimilitude in terror and looks for sanctuary in the Cuenca Cathedral, a huge 13th-entury Gothic edifice that is the one piece of the real world here that stands up to the awe of Harryhausen’s miniatures-made-monsters. Gwangi busts in and the villagers flee as the lead cowboy distracts him by making noise on the organ; he then javelins a flag into Gwangi’s side and sets the whole place on fire. There are at least two and possibly three planes of existence here — the actual church, Gwangi writhing and shrieking in agony; and the fire that may or may not be part of Gwangi’s shot, and they come together in a unified whole of pity and terror. While this could have been played as a demon being taken down by the Church, it instead is a portrait of collapsing majesty. Literally, as the building falls in on itself and finally crushes Gwangi. Outside, that damn wiener orphan partially redeems himself by weeping. And it’s hard for viewers to not shed a tear themselves. The noises Gwangi makes are truly awful, and that sense of tactility that made him so powerful now reinforces the idea that something real is being destroyed.

“Nobody cry when Jaws die,” Dino DeLaurentis allegedly said while promoting his own remake of King Kong, drawing a pointed comparison to how he anticipated audiences would react to his beast’s fall. Some monsters’ deaths are cause for celebration, but we mourn the loss of others because, while they may be scary, they are also awe-inspiring in how they move, how they seem perhaps not real but vital on the screen. This vitality is part of what made and makes those earlier comparison points of 2001 and The Wild Bunch so powerful as films in their own right — the menace and pathos of HAL, the menace and pathos of Warren Oates. Gwangi goes out in a blaze of glory like the Wild Bunch but like Dave Bowman, he’d travel to the future, where his attack on that hapless Ornithomius would inspire a similar display of prehistoric power when the T. Rex leaps into a herd of fleeing Gallimimus in Jurassic Park.

That attack was rendered on computers and is amazing in its own right. There is no single way to create awe. But what Harryhausen and his team accomplished here with the tangibility of stop-motion remains awe-inspiring, moving, rad as hell. Willis O’Brien apparently had another story in the works that never got made, War Eagles, which Dr. Wikipedia summarizes as “a race of Vikings riding on prehistoric eagles fighting with dinosaurs” and what is stopping someone from jumping on this incredible idea? Harryhausen died in 2013, but we still have cameras and clay. An awesome world is waiting to begin.