The Most Dangerous Game is one of those tales, like The Monkey’s Paw, that feels like it was always floating around in some form or another until someone finally set it down in print. Man hunting man is a primal theme. The tools may change but the idea resonates backward — we’ve definitely done this for a while — as well as forward, from your Running Mans to your Hungers Games. It’s a great story. But a story isn’t necessarily a movie.

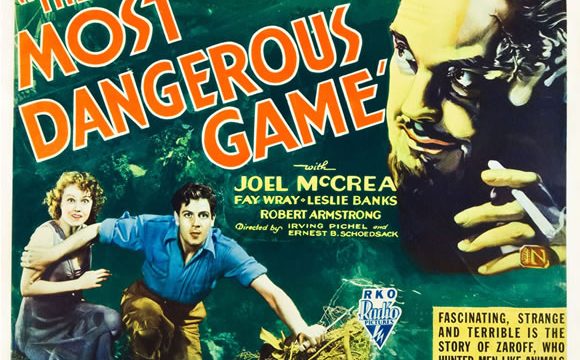

Richard Connell’s short fiction could probably be filmed with few variations. There’s a fair amount of action as great white hunter Rainsford is first rescued and then stalked by the menacing Count Zaroff and his Russian lackeys. There are enough reversals and survivalist tricks to carry a feature, and considering the relative lack of dialogue, that feature could be silent. There are hints of this in Irving Pichel and Ernest B. Schoedsack’s adaptation, but RKO was in the business of making movies, and movies have dialogue, and drunks, and most importantly, dames. Even though this adaptation clocks in at barely over an hour, it crams in a lot of stuff extraneous to the story.

Sometimes this works. The opening sequence with Joel McCrea’s Rainsford and his chums aboard a boat is a decent exposition dump that is ruthlessly ended once all useful information has been provided — the boat runs aground, most people drown and two people are definitely eaten alive by sharks (making a credible run of their own for the title of Most Dangerous Game). And as ZoeZ has noted, Rainsford’s rescue and subsequent entertaining by the nefarious Zaroff — who like most Russians has an entire mansion on an otherwise uninhabited island — is good creepy Gothic fun. Rainsford and a few other rescuees hang out in the huge parlor with its yards-wide staircase as Zaroff (Lesie Banks, wide-eyed and skeevy-bearded) acts increasingly creepy. The Gothic atmosphere thrives on the tension between what is clearly wrong and the people who might recognize it but for reasons of propriety or fear can’t act against that wrongness, something that’s played very well here. And the production design is fantastic: the cavernous room dwarfs its inhabitants and the mansion is full of creepy art, with a brutish centaur motif that suggests ravishings to come from someone who will use power any damn way he pleases.

But wait a minute. Who are these other rescuees? Fay Wray and Robert Armstrong are Eve and Martin Trowbridge, sister and brother who have also been shipwrecked. A few other people came with them, but they’ve disappeared after seeing Zaroff’s trophy room. The pair helps build tension through this long scene, and they occasionally release it — Armstrong is a pretty amusing blithe drunk, over the top in his sloppiness but funny enough to get away with it — and they also give the movie some space so it isn’t just Zaroff and Rainsford talking while Zaroff’s silent manservant Ivan glowers. And Wray plays Eve with wit and toughness that admits fear and tamps it down. Unlike her brother, she realizes something is very wrong here and that Rainsford is their best way at getting out of it.

Which is what makes the turn so disappointing. Zaroff kills Martin, Eve and Rainsford discover his body, and Eve turns into a screaming damsel in distress. Obviously Fay Wray is going to scream — you wouldn’t cast Louis Armstrong and not ask him to play the trumpet — but the competent dame from earlier is gone. And instead of Rainsford going off alone to be hunted, now he’s dragging her along. This gives Rainsford a sounding board to describe what he’s doing at any given time, a narrative convenience that fortunately stops short of Mant!-like mansplaining, but it’s still a drag on what should be the leanest, tensest part of the movie.

Even with Wray slowing him down, Rainsford does his best. He creates a few nice traps that Zaroff barely avoids and eventually Zaroff has to resort to that most Burnsian of actions, releasing the hounds. And aside from their barking and the score, we’re finally free of dialogue and the images can carry the day. It’s a frustrating sequence in some ways — the cutting is pedestrian and goes between three groups (Rainsford/Eve, the dogs, Zaroff /Russians) covering the same ground in an enervating rhythm. But the ground they cover is fantastic, largely made up of sets that the movie shared with King Kong. A foggy swamp is a thick wet haze, with the enveloping grey turning people into the kind of shades you can only really get with black and white. The heroes cross a bridge made by a massive fallen tree that dwarfs them, turning them into fairy-tale children. And they are run to ground behind a wildly flowing waterfall that Rainsford plummets into after throttling one of Zaroff’s dogs. This is a glimpse of a movie that could have been, a nightmare chase that strips away any tricks the prey has to discourage the hunter.

Zaroff captures Eve and is pretty open about raping her once they get back to his manse — it’s not the first time he’s alluded to this (remember those centaurs) but now he’s ready to embrace all aspects of the superiority he feels through hunting, the ability to take because he can. Zaroff’s faux-Nietzscheisms are an underexplored theme of the movie for the most part, but the ending makes up for it. Because of course Rainsford survived, swam to the mansion, and is ready to kick some ass. McCrea is not very charismatic here (he’s not asked to be much more than a handsome body; Armstrong may be broad in his drunkenness, but he makes a stronger impression as a person) but he is convincingly pissed and even more convincingly violent — he wastes every Russian within mauling distance and ends a brutal fight with Ivan by getting back to back with the Russian and snapping the Cossack’s spine. It’s an MMA move by a person who has fully embraced Zaroff’s philosophy of hunt or be hunted. Eve is sadly back to screaming mode, which at least is a useful warning system when someone is throwing a knife.

So it would seem Rainsford is making a play for apex predator, but while he wounds Zaroff, he decides to get while the getting is good and flees with Eve in a small boat. This leads to a curious ending where the focus is entirely on Zaroff. He stands in the window, a noble pose, as he pulls back his bow to drill Rainsford with an arrow. But he’s too weak. He can’t maintain the tension. He collapses, a man thwarted at the last minute — all of this is framed in a nearly tragic way — his loss of power is more meaningful than Rainsford’s rampage. Then he falls out the window to the waiting dogs below, where he is totally eaten offscreen just like those shipwreck victims were by sharks. The End!

It’s an abrupt conclusion, although a satisfying one. And while the movie is clearly not endorsing Zaroff’s ideas, it seems to prefer him as a character. Bad guys are always more fun, of course, and Banks has a fine time delivering his evil ideas, but the film never lets Rainsford be truly tested by Zaroff’s contest, to explore his own capacity for the hunt and what it means for his sense of self. The story’s ending is slightly more ambiguous — we don’t see Zaroff die — but it’s clear that Rainsford killed him and presumably gave the dogs a meal. The hunter was slaughtered by the game, and what does that make the game then?

Maybe that didn’t fit with the movie RKO wanted to make, where the hero is clear (after all, they invented a girl for him to get — how much more obvious can a hero be?). And on its own, the movie is fine. The basic story has been around for a long time and can exist in many ways. It’s a folk song. But as an adaptation that pulls the most from what the idea has to offer, the movie misses the mark. The Most Dangerous Game remains elusive.