The biggest horror hit in 1996 was Scream, which revived Wes Craven’s career, and launched Kevin Williamson’s, and shaped a lot of scary movies (and Scary Movies) to come. A horror movie about horror movies, where the boogeyman is not supernatural or uncanny but…nerds who know a lot about horror movies. But horror doesn’t need to be about itself, and it doesn’t even need to be scary. Like a fungus, it sprawls on its own terms, in weird places. The Antipodes, for example, where oddballs working in a very malleable genre took it to places loopier than the self-reflexive circle of the meta-slasher.

After terrorizing New Zealand for a decade, master of bad taste (and Bad Taste) Peter Jackson made The Frighteners, his first movie with American money and backing, via Universal Pictures. And as the opening credits roll, a few names appearing before Jackson’s suggest some New World influence on a distinctive voice. The first — if we hadn’t already discerned this from the ominous harpsichord soundtrack — is Danny Elfman on soundtrack duties, giving this the full heebie-jeebie Beetlejuice treatment (the initial camerawork as this is going on is not dissimilar to Tim Burton’s either). And the executive producer is America’s foremost practitioner of special effects as applied to popular entertainment: Robert Zemeckis — who was originally slated to direct before deciding Jackson was the better man to helm this tale of Michael J. Fox’s cynical psychic who realizes he’s on the trail of a ghostly serial killer slaughtering his hometown.

Half of Fox’s performance is Bill Murray in “they hate this” Ghostbusters mode, cynical and conning rubes, but the other half is tortured by the memory of his wife, who died after a car crash he caused. And while he exploits people with fake “hauntings,” the paranormal activity is real — he uses his ability to talk with ghosts to get some ectoplasmic buddies to pull poltergeist routines that he can “exorcise” for a fee. Solid enough, but Jackson and co-writer/wife Fran Walsh quickly pile on the killings of a creepy, Grim Reaper-esque ghost who is mysteriously stopping people’s hearts; the burgeoning relationship between Fox and Trini Alvarado (who should carry business cards saying, “ LEGALLY DISTINCT FROM ANDIE MACDOWELL”) as the widow of a man murdered by said ghost; a feud between Fox and the local paper; a feud between Fox and the psychotically unbalanced FBI agent who thinks he’s behind the recent deaths (an intense Jeffrey Coombs, creepier than the ghosts); and the weird activities of the recently-released-from-prison girlfriend of a psycho who was executed decades ago after a murderous rampage. Surely this dead person could not be connected to the ongoing supernatural murder spree?

The movie is full of ghosts attacking humans, humans attacking ghosts, humans attacking humans and ghosts attacking each other. And while there are some rough spots, the special effects work, by the then-obscure Kiwi company Weta, is mostly great. At least it is in my VHS copy, and that’s the tech of the times. Weta uses rough textures and rough motion to their advantage, making the Reaper killer’s uncanny movements part of his character, and Jackson understands how to place special effects in a moving frame to let the eye catch their movement without clocking any incongruity in the scene itself. (And just as an action director, Jackson is in fine form here — a sequence in a cemetery as various protagonists and antagonists fight each other, switching opponents and moving in and out of the foreground, is great.) For the many interactions with the “normal” spectres, who are ghostly echoes of how the characters looked at the moments of their deaths (Chi McBride, one of Fox’s accomplices in poltergeist chicanery, apparently kicked the bucket on the dance floor of Studio 54), the movie uses compositing and split screen, merging altered shots of the ghosts with Fox interacting with them.

This looks great and is very much a Zemeckis kind of effect, the kind of thing he pulled off over and over in the Back To The Future sequels. What is also Zemeckis-influenced, to an acceptable degree in the movie but odd in the context of Jackson’s previous work, is how these supernatural beings can be messed with. They can be harmed by their fellow undead — one has his face torn off — but the world of the living just goofs on them: a car running over a ghost will dent it in the manner of a Looney Tune getting squashed by a jalopy. What should be the goriest moment in the film, when a head is blown away by a shotgun, is handled with CGI that cost thousands of dollars and looks like an arcade rail shooter. The old Jackson would’ve used some papier maché and corn syrup, and it would’ve looked awesome. Zemeckis avoids blood, Jackson never met a body he couldn’t turn into chunks of meat.

But Jackson also wants to stitch these chunks back together. His greatest strength as a filmmaker, which is also his greatest weakness, is the willingness to risk making a huge mess with the parts he puts on the screen. Dead Alive has a rom-com-worthy flirtation between two people in a convenience store and a sad farting zombie intestine; Heavenly Creatures has Claymation dream sequences, horny desire for Orson Welles, the incandescent desire of teenage friends, and a death that feels like an actual obscenity. The Frighteners is trying to be the story of a man realizing he’s been pretending to be alive, the story of that same man stopping Ghost Charles Starkweather, and the story of ghosts knocking around on earth and occasionally trying to bang mummies in the history museum. It doesn’t do this without missteps, but it does all come together at the end. I don’t think anyone watching The Frighteners at the time would immediately conclude that its director and writers would make The Lord of the Rings; watching it now is like seeing a demo for that series’ merging of horror and humor and bringing out emotional truths with special effects. But it’s easy to watch this after Peter Jackson became the biggest director in the world and see the abilities that got him there.

Brian Trenchard-Smith has been making movies for 40 years, mostly in Australia, and has never sniffed a budget a tenth of what Jackson had for The Lord of the Rings. Like Jackson, he came up making trashy movies and, based on my limited experience, has a similar philosophy of starting a movie at 7 or 8 and going not to 10 or even 11 but 15 if he can swing it. He directed the second Leprechaun sequel, which takes place in Las Vegas — a place connected to luck and still on earth, where leprechauns are generally presumed to reside.

But Leprechaun 4: In Space, is, well. It opens with your standard Space Marines going on a mission. The mission is to rescue a Space Princess from an unspecified Space Other Culture. Said princess is being held captive by the Leprechaun on another planet so he can woo her, wed her, and become a Space King. This is all laid out in dialogue but never actually explained. I’m given to understand previous Leprechaun flicks revolved around various gold issues, rather than Space Succession, but while Jackson and Walsh respectably wrap up their various plots, Trenchard-Smith and writer Dennis Pratt know that reason does not actually matter here.

What matters is the Space Marines showing up to rescue the princess and blasting the Leprechaun (played, as always, by Warwick Davis, cackling and corny and fun) into a puddle of goo; one Marine triumphantly pisses on said goo puddle which allows the Leprechaun to magically hijack his urethra for the purposes of resurrection. As Athena sprang fully formed from the forehead of Zeus, the reconstituted Leprechaun later blows out of said Space Marine’s dick. Athena’s birth is seen as a metaphor for inspiration, the idea exploding out of the skull; what we have here speaks to inspiration in its own way.

Because why not a Leprechaun, in Space? Why not throw him loose on a spaceship that also has a mad scientist, ominously seen only via monitor for the first half of the movie, as well as that horny and manipulative princess from the beginning of the film? That mad scientist, essentially a Nazi with only a torso named Dr. Mittenhand, is keeping spiders in his lab for some reason, and you better believe that the Leprechaun forces him to drink a DNA cocktail made via blender with extra tarantula. Dr. Mittenhand soon needs eight mittens. This comes around the same time the Leprechaun uses his magic(?) to make the hardass Marine leader, a cyborg with a visible robot skull, succumb to his subconscious urges, which are apparently to dress in drag and kick the shit out of people on the ship’s disco dance floor. Why not?

In the early ’80s, Trenchard-Smith was given some money and a shitload of stuntmen to make his movies; here, he has a dozen people, all of whom have been introduced (and some killed off!) in the first 20 minutes, a bunch of sets made out of foam rubber for a fake planet, and some steam-blasted catwalks and beepy monitors for the ship itself. But while this is cheap, it is the best it can be while being cheap. Nothing is half-assed here. The movie seems to be shot on the cheapest of video (and in fact went straight to VHS); more than anything else, it looks like a softcore porno, pretty far away from The Frighteners’ Zemeckis-enabled shoot. Looking for horror here is like trying to find eroticism in Lord of the G-Strings. Instead of boobs and chicks making out, we have deaths of various gore levels delivered like clockwork and without any real menace (don’t worry, there are also boobs here too).

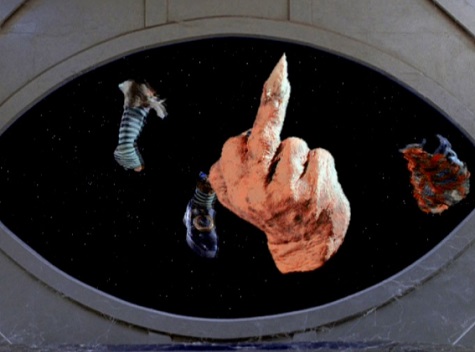

But just because Leprechaun 4: In Space is not scary does not mean it is not successful. Like Jackson, Trenchard-Smith knows that you can be silly and still be entertaining. What you need is commitment to the bit. The acting in L4:IS also calls to mind the quality of porno flicks at times, but the actors deliver their lines with enthusiasm, and Tim Colceri’s Marine leader and Guy Siner’s campy Mittenhand stand out. Their job is to help take the movie as far as its already-ridiculous premise can go, and Trenchard-Smith’s job is to show this with clarity and flair. There are no One Perfect Shots here but plenty of gross reveals. They work in sync so that we can watch an embiggened Leprechaun trying to step on helpless Marines while spider-Mittenhand writhes in agony (the giant Leprechaun is made with some dodgy CG and trick photography, Mittenhand with delightfully gross practical costuming) before the remaining Marines blow the Leprechaun out the airlock so he can explode in the vacuum of space. Does the giant severed hand of the Leprechaun give our heroes the finger right before the credits roll? You’re goddamn right it does.

The Frighteners has a little too much polish overriding its director’s personality sometimes. But it ends with Jackson going full-bore into gleeful serial killing. After teasing it the whole movie, he shows manic Jake Busey and the great Dee Wallace in slaughter mode, mowing down hospital patients. This is before they’re dragged to a hell of hentai demon serpents, the one instance of CGI that really does not stand up at all but that’s gnarly enough in concept to still be cool. He might miss, but Jackson swings big.

He and Trenchard-Smith understand maximalism, the value not just of explosions in a movie but exploding a movie beyond where it started and how much fun that can be. Even with limitations. A few years after Leprechaun 4: In Space came out, Trenchard-Smith described his working philosophy in an interview: “Deliver the goods, above and beyond creative and fiscal expectations. Mr Reliable is a popular guy. Specialise in the difficult. No task too great, no budget too small. Work breeds work, particularly if you leave your producers smiling rather than unhappy. Low-budget genre filmmaking does not mean you have to check your personality at the door.” Horror lets Jackson and Trenchard-Smith express their personalities, which love gore and excess and goofiness and love throwing all that at the viewers, so much of it that it’s hard to keep up sometimes. In degeneracy, generosity.