Even coming back to him for the umpteenth time, decades down the line, Stephen King can still shock you. He got me as I was reading Rage, a story of a high school student named Charlie Decker who snaps and takes his algebra class hostage, shooting and killing two teachers in the process. The teachers, one male and one female, are barely in the story, and my mental image of them has always been a vague impression of balding bachelor and snappish spinster, but the narrative lays it right out there: They’re both 37, which happens to be two years younger than I am now, and how did that happen?

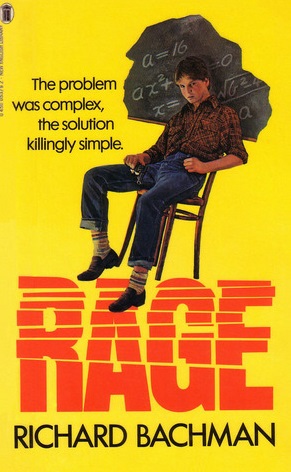

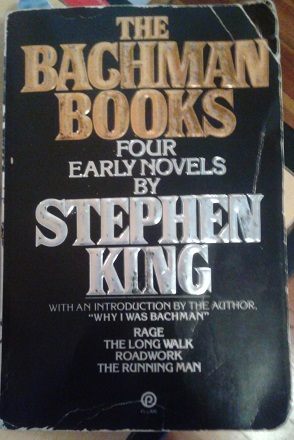

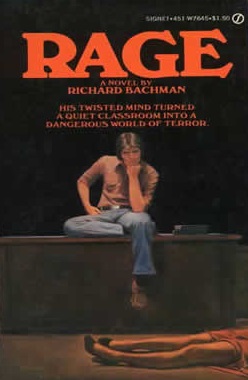

King being who he is, he will also not shock you in other ways. His vulgar skewed colloquialisms are entirely his own, like this from the book’s second paragraph: “The lawn of the Placerville High School is a very good one. It does not fuck around. It comes right up to the building and says howdy.” In retrospect it is hilarious that publishing this under a pseudonym, the first of five books written as “Richard Bachman,” managed to fool anyone. And as King himself notes, it is pretty amusing that these novels were small potatoes when originally published but sold very well indeed when their real author was revealed.

The other Bachman stories are still in print, but in the 1990s King pulled Rage after it was linked to numerous school shooters. If not a shock, it’s a bit of a surprise — King has written lots of stories about violent and vengeful children and burst onto the literary scene with a book about a teen girl who burns down her high school with everyone inside, so why yank this one? In an essay about gun violence that doubles as explanation for pulling publication, King is clear that the teenagers who read Rage and murdered people at their schools were damaged by bullies and bad parents and were dealing with their own mental health problems, that his book did not cause them to pull the trigger. But the association with his book was there, and worth stopping: “I pulled it because in my judgment it might be hurting people, and that made it the responsible thing to do,” King writes, adding he didn’t want to give people “blueprints to express their hate and fear. Charlie had to go. He was dangerous. And in more ways than one.”

Rage was originally written in the late 1960s, when King himself was in high school, and “Richard Bachman” found the manuscript and rewrote/revised it before publishing it in 1977. “I was still callow enough to believe in oversimple motivations (many of them painfully Freudian),” King writes in an introduction to The Bachman Books, a collection of the four novels written under that name before the King link was discovered with the publication of Thinner, and Charlie indeed wants to kill his asshole overbearing father while being much more attached to his nurturing mother. Charlie’s sex life is full of impotent embarrassments, and half of the novel is him laying out all of this, How I Got Here, to the class he’s taken captive. And the novel’s original title, Getting It On, is of course loaded with sexual import and is more specific (and frankly King-ier) than the generic Rage. Which is part of Charlie’s makeup but not what makes him dangerous.

For Charlie, “getting it on” is a matter of power, pushing back on the parts of society that are at best indifferent to his pain and at worst condescending and cruel about it, insisting his existence be stretched and sliced to the Procrustean bed of “normal” life. It’s about upending the dynamics of school authority, first outwitting his principal and then psychologically breaking his guidance counselor (the two teachers he actually kills really have nothing to do with him personally, they’re just cogs in the machine he’s raging against). Charlie isn’t dour or (overly) vicious, his narration of the tale recognizes its dark humor and he has a fun cynical edge, like an aside on the teacher’s pet: “a cinch to speak a piece as valedictorian in June — ‘Our Responsibilities to the Black Race’ or maybe ’“Hopes For The Future.’ She was already signed up for one of those big-league women’s colleges where people always wonder how many virgins there are. But I didn’t hold it against her.” But Charlie is sick and wants everyone to recognize their own sickness. What makes him dangerous is how, in the other half of the book, he is successful.

Because when Charlie takes over his algebra class and starts to get it on, much of the class winds up joining him. His stories are listened to with attention, and as officials school and otherwise try to negotiate with Charlie, the class starts to tell stories of their own. The pretty valedictorian feels trapped by expectations, and the nerd is stifled by his mother. The town tramp and the ugly duckling get it on in a vicious slapfight before a draw is declared, with both of them accepting what they most despise in themselves. When Charlie breaks his guidance counselor, it’s a savage, ugly owning, and it rules, but he winds up as a twisted version of a counselor himself. He leads his fellow classmates to their own recognitions and gets to play Sorcerer’s Apprentice in doing so, having the power to let them loose and the excuse of being unable to stop them when they really get going: “Things had gotten out of control. There was no real way that could be denied anymore. I had a sudden urge to laugh at all of them, to point out I had started out as the main attraction and had ended up as the sideshow.”

There’s one student who doesn’t play ball, though: Ted Jones, golden boy and former star quarterback. He keeps trying to play the good guy, the square-jawed hero who’ll take out the terrorist, and more importantly, he refuses to wallow in the muck with his fellow students/group therapy members. That town tramp admits that her mother sleeps around but she loves her anyway; when it’s revealed that Ted quit the football team because his mother’s an alcoholic (parents are pretty bad news in this book) he calls her a bitch, not so much for being a drunk or a bad mom but for this revelation destroying the image he’s cultivated for himself.

“I was beginning to suspect that Ted was to my classmates what Eisenhower must always have been to the dedicated liberals of the fifties — you had to like him, that style, that grin, that record, those good intentions, but there was something exasperating and a tiny bit slimy about him,” Charlie says. Isn’t this the secret dream of the miserable? Not just that the popular kid has his own problems, but that he’s not actually liked? Ted refuses to get it on and admit he’s broken, and in the end the rest of the class — with Charlie hanging back, watching — decides to break him, beating and tormenting him until he’s catatonic.

I have a lot of sympathy for Ted. Being forced to talk about my private life in a group setting that I haven’t chosen sounds like hell. And beyond that, like Ted I have an instinctive rejection of the kind of disorder Charlie brings. In Winnie-the-Pooh terms, we’re both Rabbits: the casual acceptance of insanity is worse than the insanity itself. “You’re all crazy!” Ted tells his classmates in one of the last moments he’s capable of speech, and he’s not wrong. But he’s missed the point. It’s not his world anymore, it’s the world Charlie set in motion and that everyone else has signed on to, and that means it’s the real world now.

Rage ends with Charlie letting his charges go after they turn Ted into a vegetable and then attempts suicide by cop. He survives, though, and is shuffled off to a mental institution, where he gets a letter from a friend hinting that the students who he held hostage have gained some new independence in their lives. This is by far the closest thing to a happy ending in The Bachman Books, which all end in suicides — Charlie’s attempt in Rage, an insane bodily self-destruction in The Long Walk, a last stand shootout ended with dynamite in Roadwork, a man flying a 747 into a skyscraper in The Running Man. In that same introduction where King bemoans his Freudian issues, he grimaces at the downer endings of these stories, likewise writing them off as immaturity.

King originally wrote the second book in the collection, The Long Walk, just after Rage, when he was in college. It also concerns high school-age teens, although here they are participating in a dystopian contest of continuously walking until all but one dies. King has always been a big fan of epigraphs, and here he includes a passage from Thomas Carlyle: “To me the Universe was all void of Life, or Purpose, of Volition, even of Hostility; it was one huge, dead, immeasurable Steam-engine, rolling on, in its dead indifference, to grind me limb from limb.” This image, of a death train shrieking onward, running over any and all, occurs to The Long Walk’s hero in the story’s text and shows up as well in the subsequent two novels collected here, in which a man mourning the death of his son tries to stop a city road project from destroying his home and another man is hunted in another dystopia, where The Most Dangerous Game has become a game show that feeds on the poor in order to keep them from revolt.

Dystopian governments running rigged contests, City Hall and cancer, school and Mom and Dad. King is the king of horror and Thinner, the final Bachman book until King revived the pseudonym in the ’90s, is explicitly supernatural in its tale of a “Gypsy” curse — while it shares a certain grim vibe, it stands apart from these previous four stories set in the real world or speculative near-futures. Horror so often boils down to fear of death, but what these books dig into is worse than death. It’s a life of misery with no fantasy, of being crushed by institutions so disinterested in your existence and so far beyond your control that death starts looking like the one thing you can own. It’s a world where the constants are pointlessness and pain. Sounds a lot like high school.

Most of that essay about gun violence King wrote does not concern Rage; it’s more interested in the firearms themselves, statistics and cultural pondering and King in “Uncle Stevie But Stern” Boomer lecture mode. But when he does address the novel itself, even as something he no longer wants in the world, he is honest about what it offers:

“It contained a nasty glowing center of truth that was more accessible to me as an adolescent. Adults do not forget the horrors and shamings of their childhood, but those feelings tend to lose their immediacy (except perhaps in dreams, where even old men and women find themselves taking tests they have not studied for with no clothes on). The violent actions and emotions portrayed in Rage were drawn directly from the high school life I was living five days a week, nine months of the year. The book told unpleasant truths, and anyone who doesn’t feel a qualm of regret at throwing a blanket over the truth is an asshole with no conscience.”

Despite that earlier reference to Rage as a “blueprint,” there’s nothing in it that could possibly be useful on a practical level to a kid looking to murder his classmates. But it does have something less tangible and more insidious as inspiration, I think. Charlie regrets shooting his teachers, but there’s no description of what their deaths mean to family and friends. Their deaths are abstractions. Some other teachers and administrators have a tough time, but fuck them. Charlie gets it on, but his classmates get it on with him, and they are the ones who destroy Ted Jones. There is no real responsibility here for Charlie, but plenty of consequence for everyone else. He derails that seemingly unstoppable train and everyone else has to clean up his mess. I can see the allure.

King would handle teenage destruction with more skill and more power in the queasy and evil Apt Pupil, which also has its protagonist commit mass murder, but that’s about a kid who teams up with a literal Nazi — not a lot to empathize with there. And he’d tap into a sadder and deeper rage in Carrie and Christine, but those draw on the supernatural, on fantasy that can never be fully realized. Rage is the clumsiest and weakest of the Bachman books and part of that is because the clumsiness and weakness of teenagers has a horrible potency that King rightly notes is lost over time, diluted by years that didn’t suck and days that didn’t have the potential to be so awful that destruction could seem like a good idea. In Roadwork, a guy in his 40s reaches the same conclusions Charlie does and acts violently, but King doesn’t see the need to pull the adult’s story of negation away. Despite Rage’s low stakes and often awkward writing, its evocation of the bleakness that courses through The Bachman Books and the self-pity and despair and yes, rage that accompanies it is powerful and true. It’s not a blueprint, it’s a mirror, and we all know the story of the mirror so compelling that the viewer falls into the image.

At least, that’s what I see now when I look at the book through a glass darkened by decades. I enjoyed Rage when I first read it in middle school; I’m pretty sure I was happier to see Ted turned into a vegetable then. But I’ve never been a huge fan of the book, not the way I am of Christine and its mirror to my bitterly amused and angry life as an adolescent. Like King says, the immediacy of my bad feelings from those times has faded, but what has stuck with me is the original shock of recognition a few chapters into Christine, where it felt like the book was pulling my thoughts out of my head and putting them on the page, like it was reading me. King made his calculus to remove Rage based on lives destroyed, and I honestly can’t say I wouldn’t do the same, but you can’t see the lives saved or salved in the same way, can you? I hope Rage still finds the people who need it, because while it’s hard to see from where I am now, I know there are times when it feels like the rage and despair will never go away.