Back when I was smoking, I had three rules: no smoking in front of my parents, no smoking indoors, and no smoking at work. The first two were easy enough to follow, but there was a fair amount of temptation to break the third, because it offered a break. What’s just as calming as the smoke is the space it creates, where you’re doing something but also nothing at all, conscious of the cigarette running down but existing in the moment that’s still there. I figured tying that to an activity that torches your lungs and lifespan was not a good idea. Maybe there’s another way.

In Joe South’s 1968 smash “Games People Play,” the way is fraught with peril — false lovers, religious hucksters, lying politicians. “Whoa, the games people play now/Every night and every day now/Never meanin’ what they say now/Never sayin’ what they mean,” South sings over a sitar line that doubles the vocal melody. And it’s a great melody, an instantly hummable rise and fall that splits the difference between resignation and acceptance. The Grammys named it Song of the Year in 1970 and it’s been covered again and again through the years. Wikipedia lists Mel Tormé and Tesla, who apparently performed their song “on their 1994 album, Bust a Nut,” along with contemporaries of South like Don Gibson and the Everly Brothers.

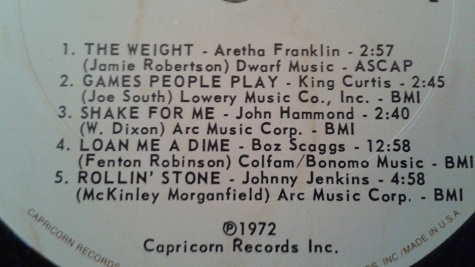

Saxophonist King Curtis (born Curtis Ousley) jumped on the song too. A decade after laying down the most joyful sound of the century on the Coasters’ “Yakkety Yak,” Curtis had become one of the great session saxophonists, a top sideman (he led Aretha Franklin’s backing band) and a bandleader/arranger with several albums and a couple well-performing soul and R&B singles. He also had become close friends with a kid 13 years younger than him who was also a crack session player in the process of becoming a frontman — Duane Allman. The two had played together on Aretha Franklin’s cover of “The Weight,” and if you haven’t heard that then what the hell are you waiting for:

Curtis was a huge fan of the blues and early on in his career released a blues album where he mostly set the saxophone down to sing and play guitar instead — maybe he and Allman connected over that. More likely, they just recognized a shared sensibility, a playing style that was laid-back but not lazy. A flow that could be fast but rarely rushed, and purposeful even then. Allman was a natural choice to sit in on a song built around a twangy melody. And the natural place to record it was down in Muscle Shoals, the Alabama studio where Allman had just sat in on Wilson Pickett’s recording of “Hey Jude” and you know what to do by now:

Rock and pop lyrics succeed or fail based on how they’re sung, not the words themselves or their poetic qualities. South’s lyrics are a list of burdens that he soulfully shoulders, and the rising orchestration behind him helps him carry that weight. The words are simple, and South pushes them toward profundity, but they’re still a burden on the tune itself, and South knows it — a good chunk of the chorus is “lah dah de dah”s. Allman’s electric sitar carries the melody in a similar way to the original, although he gives it a heavier, swampier sound and also lays back further at times, making his entrance in the second verse that much meatier.

But it’s Curtis who takes the vocal line free of words with his wonderful, slightly breathy tone. It’s different from delicate: it’s light and it lightens the load that South’s words place on his music. Curtis guested on Sam Cooke’s Live At The Harlem Square Club, one of the greatest live albums ever recorded, and he shares Cooke’s ability to suggest sorrow as he moves above it, like seeing the clouds beneath a plane. Sadness and sweetness, a soul serenade.

The musicians behind him fill in and push like the pros they are — Jimmy Johnson on rhythm guitar and Berry Beckett on piano flesh out the harmony while Roger Hawkins on drums and David Hood (father of the Drive-By Truckers’ Patterson) on bass get so deep in the pocket they’re down by the shin bone; their groove is the undertow of Curtis and Allman’s flow. While Allman spends most of his time on the sitar, he steps in with his trusty slide for a few fills, including a great, bluesy lick leading into the final verse. It’s the kind of thing the song could exist without (South’s version does) but if its perfection in the moment doesn’t justify its existence, what kind of justification is needed for something like that? It just is.

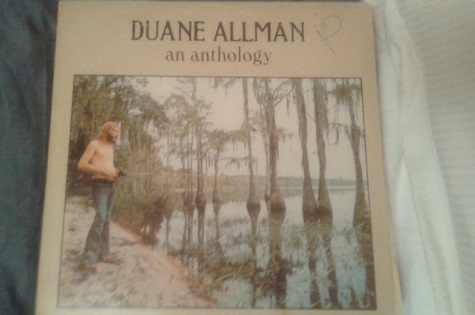

“Games People Play” was recorded in February 1969, for Curtis’ Instant Groove album. In August 1971, he was coming back to his Manhattan brownstone on a hot night with a new air conditioner and told two arguing junkies to get off his steps. One of the junkies stabbed Curtis, and while Curtis pulled out the knife and chased his attacker down the street with it, he died almost immediately. Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, and Jesse Jackson came to his funeral, as did Duane Allman, who a few nights later played a wrenching and joyous version of “Soul Serenade” at an Allman Brothers show. Three months later. Allman himself would be dead in a motorcycle crash, and the double album Duane Allman: An Anthology came out in 1972. Maybe it was a cash grab, but it collected a ton of side work, including “Games People Play,” and it’s how I know the song — first snagged somewhere online and then when I found the original LP in my parents’ record collection.

It’s funny how we come to things, through circles and side routes instead of straight on. (If anyone has a copy of Instant Groove, hit me up.) There’s an old, supposedly Buddhist parable that I first heard watching King Of The Hill. A man is chased off a cliff by a tiger, grabbing a vine as he goes over the side. Caught between a murderous beast above and a deadly fall below, he sees a strawberry on the vine and eats it, saying “What a delicious strawberry!”

At the end of “Games People Play,” as Allman kicks it over to that final verse, the band is at full strength, some background horns provide a counterpoint, and Curtis takes leave of the melody for a minute; the song is burning out, and he solos for it and with it, holding a high note that he caps with a three-note punctuation — doo-dee-dah! Curtis sees the ending coming and makes it irrelevant; he sees it coming and plays in the moment and that little capper right before the final fade is him closing the space Allman opened with his sitar riff. Every time this part begins I know the song is coming to an end and the spell it casts will be over, but at the same time, I know that doesn’t matter, and it’s not just because I can always listen to the song again. What matters is the space in the song, the beginning and the end and everything in between. How three minutes is a fraction of time, but it’s enough to perceive and absorb that time means less than how you exist in it. Smoke ’em if you got ’em.